Works Stage MASS: A Theatre Piece for Singers, Players and Dancers (1971)

Celebrating 50 Years of MASS

Press Release and Electronic Press Kit

Background

During his legendary tenure at the New York Philharmonic from 1958 to 1969, Leonard Bernstein composed only two works, Symphony No. 3: Kaddish (1963) and Chichester Psalms (1965). He had dedicated Kaddish to the memory of John F. Kennedy shortly after his assassination, and when Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis asked Bernstein to compose a piece for the 1971 inauguration of the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C., he was eager to honor the occasion with a new, large-scale work because he knew he had always wanted "to compose a service of one sort or another." The son of Russian-Jewish parents, a social liberal, and lifelong activist, Bernstein made a surprising choice: the Roman Catholic Mass. But instead of a straightforward, purely musical setting of the Latin liturgy, he created a broadly eclectic theatrical event by placing the 400-year-old religious rite into a tense, dramatic dialog with music and lyrics of the 20th century vernacular, using this dialectic to explore the crisis in faith and cultural breakdown of the post-Kennedy era.

By the late 1960s, the country had become polarized over U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. A powerful anti-war movement swept the nation, fueled by outrage at the draft, the massive casualties, atrocities such as the My Lai Massacre, incursions into Laos and Cambodia, the imprisonment of conscientious objectors and activists, and in 1970, the Kent State shootings. These turbulent times produced a restless youth culture that hungered for a trustworthy government and for spiritual authority that reflected their values. MASS gave them a voice.

Six months before the scheduled premiere, MASS was far from completion. Needing a collaborator, Bernstein decided to ask the young composer-lyricist Stephen Schwartz to work with him on the text. Schwartz had recently proven his ability to transform religious stories and rituals into contemporary theater with Godspell, his hit musical based on the Gospel of St. Matthew. The two writers hit it off and worked briskly to meet the deadline.

Bernstein and Schwartz envisioned MASS not as a concert piece, but as a fully staged, dramatic pageant. They mixed sacred and secular texts, using the traditional Latin liturgical sequence as the fundamental structure and inserting tropes in contemporary English that question and challenge the prescribed service, as well as meditations that demand time for reflection. They took the Tridentine Mass, a highly-ritualized Catholic rite meant to be recited verbatim, and applied to it a very Jewish practice of debating and arguing with God. The result was a piece that powerfully communicated the confusion and cultural malaise of the early 1970s, questioning authority and advocating for peace.

In MASS, the ceremony is performed by a Celebrant accompanied by a formal choir, a boys' choir, acolytes, and musicians. His congregation of disaffected youth (the "Street Chorus") sings the tropes that challenge the formal ecclesiastic dogma of the Church. As the tension grows and the Celebrant becomes more and more vested, the cynical congregants turn to him as the healer of all their ills, violently demanding peace. In a climactic moment, overwhelmed by the burden of his authority, the Celebrant hurls the sacraments to the floor and has a complete spiritual breakdown. The catharsis creates an opening for a return to the simple, pure faith with which he had begun the ritual (expressed in the sublime "A Simple Song"). Though MASS challenges divine authority, exposing its contradictions and questioning religion's relevance to contemporary life, it ultimately serves as a reaffirmation of faith and hope for universal peace.

The eclecticism of MASS's music reflects the multifaceted nature of Bernstein's career, with blues, rock, gospel, folk, Broadway and jazz idioms appearing side by side with 12-tone serialism, symphonic marches, solemn hymns, Middle Eastern dances, orchestral meditations, and lush chorales, all united in a single dramatic event with recurring musical motifs. Bernstein uses the uninhibitedly tonal rock 'n' roll of the Street Chorus to challenge the dogmatic, atonal music of the Church; ultimately, the musical argument is resolved with a glorious, tonal chorale ("Almighty Father") sung by the entire company.

MASS premiered on September 8, 1971, at the inauguration of the Kennedy Center, directed by Gordon Davidson, conducted by Maurice Peress, and choreographed by Alvin Ailey. The performance was fully staged, with over 200 participants. The pit orchestra contained the strings, percussion, a concert organ, and a "rock" organ; all of the other instrumentalists—brass, woodwinds, rock musicians— were on stage in costume and acted as members of the cast. The Street Chorus was made up of singers and dancers in contemporary dress, a 60-person robed choir filled the stage pews, and a complement of dancers costumed as Acolytes assisted the Celebrant.

During his work on MASS, Bernstein consulted with Father Dan Berrigan, a Catholic priest and anti-war activist who had been on the FBI's "10 Most-Wanted" list before being apprehended and imprisoned. In the summer of 1971, as MASS approached its premiere, the FBI warned the White House that the piece's Latin text might contain coded anti-war messages and that Bernstein was mounting a plot "to embarrass the United States government." President Nixon was strongly advised not to attend and was conspicuously absent at the premiere.

Responses to the premiere of MASS covered the spectrum. The Roman Catholic Church did not approve—some cities cancelled performances under pressure from their local Catholic churches—while other prominent clergy declared their support for the piece. Certain music critics disapproved of the mixing of genres, while others found the work to be inspired. For the most part, the audiences were deeply moved, experiencing firsthand the shared, communal journey of the composition.

Over the years, the ideas and dissent embodied in MASS, which were so threatening to the political and religious establishments in the volatile early-1970s, have become a more accepted part of spiritual and political discourse. MASS came full circle when, in 2000, Pope John Paul II requested a performance at the Vatican. Its radical mixing of musical styles, too, has also become less shocking and more accepted in the musical sphere. Time has revealed MASS to be a visionary piece that continues to be relevant and move audiences as it enjoys performances around the world.

LB100

An unforeseen success of the Centennial was the number of times Bernstein’s controversial MASS: A Theater Piece for Singers, Players, and Dancers, was performed. Nearly 40 productions took place over 100 performances, including productions in Salzburg, Vienna, Rio de Janeiro, Prague, Copenhagen, London, Paris, Leipzig, Amsterdam, Glasgow, Barcelona, Tucson, Los Angeles, San Diego, Orlando, Baltimore, Austin, New York, Cincinnati, Washington, DC, and in Singapore and Thailand. Often involving entire communities and upwards of 200 performers, audiences and performers alike embraced MASS for its relevance in today’s society; with its thought-provoking themes about violence and war, as well as questions about faith displayed through an amalgamation of musical styles, the piece seems more vital and significant now than ever. Ravinia's popular production of MASS, conducted by Marin Alsop, was broadcast on PBS Great Performances in May 2020. In addition, many of the staged works found popularity in college and university settings. Of MASS’s 96 performances, 39% were by college and university programs in the US, Germany, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Austria.

Synopsis

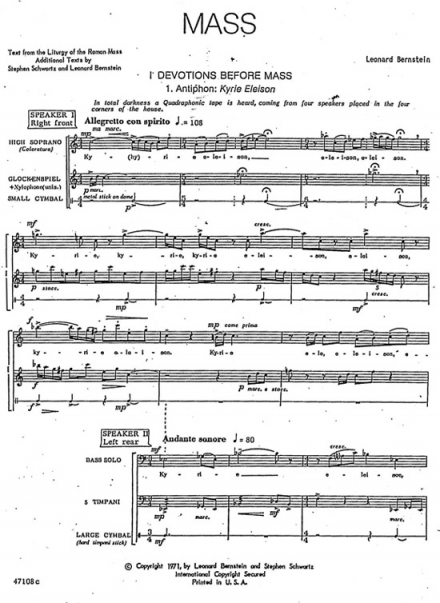

MASS begins in darkness with a pre-recorded 12-tone "Kyrie Eleison" played over four speakers placed in the corners of the house.

The cacophony created by the overlapping voices and percussion is suddenly interrupted by the simple strains of a guitar, and the Celebrant appears in street clothes, joyfully singing of the pure praise of God ("A Simple Song") . A jazzy, pre-recorded responsory ("Alleluia") completes the Devotions before Mass.

The stage is suddenly flooded with people as a festive Street Chorus enters with marching band to sing the prefatory prayers ("Kyrie Rondo"), joined by the Celebrant and Boys' Choir. After a dance, they complete the First Introit with the "Dominus Vobiscum" sung in a thrice-triple canon. The Celebrant recites "In the name of the Father" and a third pre-recorded tape features the Choir and Boys' Choir repeating the incantation ("In Nomine Patris") as the Acolytes enter, carrying ritual objects, and the Choir files into the pews and sits. A Prayer for the Congregation is sung by the Choir in a quiet chorale ("Almighty Father") followed by the pre-recorded instrumental "Epiphany."

The Confession begins with an agitated "Confeitor" sung by the Choir, but the service is interrupted by the first trope ("I Don't Know"), accompanied by rock band, in which a Street Singer questions the value of confession.

More Street Singers follow with another trope ("Easy"), a blues about how easy it is to feign piety when they "just don't care." The Acolytes adorn the Celebrant with more vestments as the Choir tries to continue the Confeitor, but the Street Singers reassert themselves.

The Celebrant offers absolution and invites the congregation to pray; an orchestral interlude ("Meditation No. 1") offers time for reflection.

A group of boys rush up to the Celebrant with bongo drums and sing an exultant "Gloria Tibi," followed by the Choir's "Gloria in Excelsis." The Street Chorus responds with a trope, questioning the relevance of the Church in the midst of so many lost souls ("Half of the People").

In the next trope ("Thank You"), a soprano sings longingly of a former time when she felt gratitude toward God. When the Street Chorus starts to reassert their cynicism, the Celebrant again invites them to pray, and all are silent during an instrumental meditation ("Mediation No. 2").

In the Epistle, the Celebrant reads a Bible passage ("The Word of the Lord"), followed by contemporary letters read by congregants. Together, they reflect on the notion that the powerful may imprison dissenters, but they "cannot imprison the Word of the Lord." Next, in the Gospel-Sermon ("God Said"), a Preacher and the Street Chorus parody the Creation story and contemporary human beings who distort God's commands to justify their own selfish needs and desires. They halt their dance when the Celebrant reappears, now even more elaborately robed.

In "Credo," a recording of the Choir singing a dispassionate, mechanical recitation of the Credo is interrupted by the Street Chorus singing a series of tropes expressing their sense that God is absent from the world and has no understanding of them. The men vent their anger that God could choose when to live and die, but that they have no choice ("Non Credo)"; a woman implores Jesus to hurry and come again as he said he would ("Hurry"); another woman sings of the world falling apart ("World Without End").

Finally, an angry rock singer gives up on a seemingly absent God and instead, puts his faith in music ("I Believe in God"). The Celebrant resumes control of the service by imploring them to pray. The Choir sings a supplication to God in a setting of Psalm 130 ("Meditation No. 3: De profundis, Part 1"), as altar boys bring the Celebrant the vessels for Communion. For the Offertory, the Boys' Choir and Choir complete the psalm ("De profundus, Part 2"), singing of God's kindness and redemption, as the Celebrant blesses the sacred Communion objects. He exits, and the ensemble dance around the holy objects with fetishistic passion.

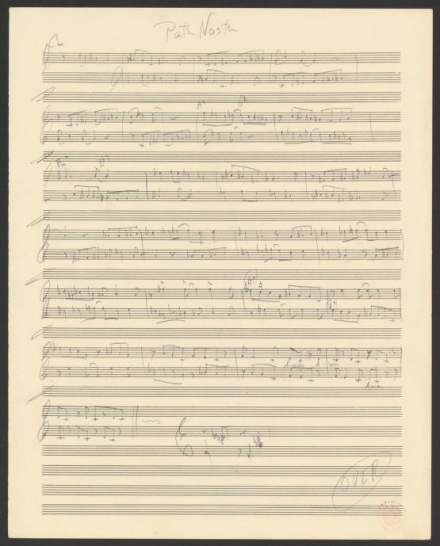

The Celebrant re-enters wearing a cope, and the ensemble backs off in silence and exits. Alone, the Celebrant recites the Lord's Prayer a capella ("Our Father"), followed by his own trope ("I Go On"), in which he sings hauntingly of persevering through times of trouble and doubt. Two altar boys assist him in the washing and drying of his hands, and he rings the Sanctus Bell. The Boys' Choir rush on stage singing a laudatory "Sanctus," to which the Celebrant, Choir and Street Chorus join in, singing in English, Latin and Hebrew.

The ensemble brings imaginary gift-offerings to him, surrounding him. As the Celebrant tries to consecrate the bread and wine for the Eucharist, the Street Chorus interrupts, singing the "Agnus Dei" and becoming fixated on the phrase, " Dona nobis pacem" ("Grant us peace"). They take over the service, singing a full-blown rock-blues protest song, violently demanding peace, joined by the Choir and instrumentalists. The Celebrant tries to continue with the Eucharist but finally the anarchy is too much for him to bear; at the climax of their protest, he hurls the raised sacraments to the floor, breaking the Chalice and Monstrance. There is a stunned silence, and all but the Celebrant fall to the ground, petrified.

In an extended aria ("Things Get Broken"), the Celebrant breaks down completely, scorning his beliefs, defiling the altar, and stripping himself of his vestments. He berates the congregation for their silence and inability to act without him, parodying back to them the "crying and complaining" of their tropes. Exhausted and embittered, he relinquishes his sacred office and leaves.

After a sustained silence, a querulous flute is heard, followed by the pure and innocent sound of a boy soprano, intoning the earlier "Simple Song" of the Celebrant ("Pax: Communion (Secret Songs)"). One by one, the congregants discover a renewed sense of faith and join the boy's song, embracing one another. Gradually, the Street Chorus, Choir, and instrumentalists all join in and pass the peace throughout the ensemble. Finally, the Celebrant reappears, dressed simply as at the beginning, and joins the boy in a canon, reminded of the simple joy of gathering together in praise. The entire company reprises the lush chorale "Almighty Father," asking for God's benediction, as the Boy's Choir passes the peace to the audience. After all of the discord, the chorale ends with a unison "Amen" and the Mass concludes with the line, "The Mass is ended; go in peace."

LB100

An unforeseen success of the Leonard Bernstein Centennial was the number of times Bernstein’s controversial MASS was performed. Nearly 40 productions took place over 100 performances, including productions in Salzburg, Vienna, Rio de Janeiro, Prague, Copenhagen, London, Paris, Leipzig, Amsterdam, Glasgow, Barcelona, Tucson, Los Angeles, San Diego, Orlando, Baltimore, Austin, New York, Cincinnati, Washington, DC, and in Singapore and Thailand. Often involving entire communities and upwards of 200 performers, audiences and performers alike embraced MASS for its relevance in today’s society; with its thought-provoking themes about violence and war, as well as questions about faith displayed through an amalgamation of musical styles, the pieceseems more vital and significant now than ever.

*Text from the Liturgy of the Roman Mass.

Additional texts by Stephen Schwarz and Leonard Bernstein. ©1971

The Norman Scribner Choir, The Berkshire Boy Choir, conducted by Leonard Bernstein.

Soloists: "Easy" - Eugene Edwards, Joy Franz and Ed Dixon, Marion Ramsey;

"God Said" - Larry Marshall;

"I Believe in God" - Tom Ellis;

"I Don't Know" - Ronald Young, Carl Hall (Descant);

"A Simple Song" - Alan Titus.

℗1971 Sony Classical. Available on "Bernstein: MASS" Sony CD SM2K63089

Related Works

Meditations from MASS

Warm-Up

Related Content

NPR: Revisiting Bernstein's Immodest 'MASS' (by Marin Alsop)

FURTHER READING: Dissertation on Bernstein's MASS by Gary de Sesa

Details

Two Meditations from MASS

(1971) 8 min

for orchestra

- Scoring: Perc(2)-organ-harp-pft-strings

Three Meditations from MASS (1977)

'A Simple Song' from MASS

(1971) 5 min

for vocal soloist and orchestra

- Scoring (Full Version): fl(off- and onstage)-perc:cyms/SD/BD(traps)/vib-Celebrant's guitar(acoustic)-2elec.gtr-elec.bass gtr-harp-big Allen org-little Allen org-strings.

- Scoring (Chamber Version): fl(off- and onstage)-perc:cyms/SC/BD(traps)/vib-Celebrant's guitar (acoustic)-2elec.gtr-elec.bass gtr-harp-org-solo vln-stringquintet(optional)

Celebrations from MASS (arr. John Mauceri)

(1999) 25 min

for baritone, boy soprano, mixed chorus, children's chorus, and orchestra

- Scoring (Full Version): 2(I,II=picc).2(II=corA).3(II=Ebcl,III=bcl).2-4.4.3.1-timp.perc(6-8)-pedal org-elec.gtr(=acoustic gtr)-bass gtr-harp-strings

Concert Selections for Soloists and Choruses from MASS

(ed. 2007) 35 min

edited for soloists, chorus, and ensemble by Doreen Rao

- Scoring: 2 (II=picc)-pft-organ-elec.gtr-bass gtr-timp.perc(5-6)-strings

Suite from MASS

for brass quintet and concert band (arr. Mike Sweeney)

To perform MASS, please contact the theatrical agent, Boosey & Hawkes. For general licensing inquiries, click here.

To purchase sheet music for MASS, please visit our store.

Media

First page of the score to MASS

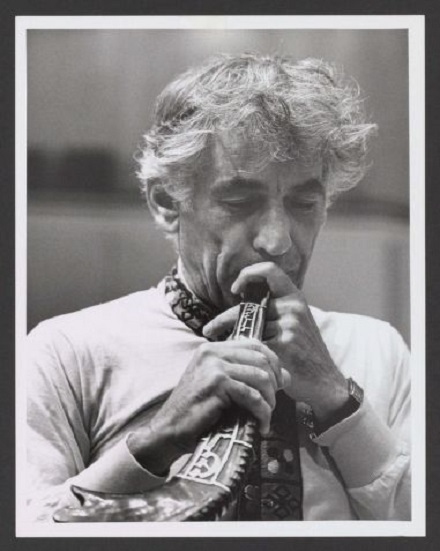

Leonard Bernstein playing a shofar during rehearsal for MASS at the Kennedy Center, September 1971

Library of Congress Digital Archives

Library of Congress Digital Archives

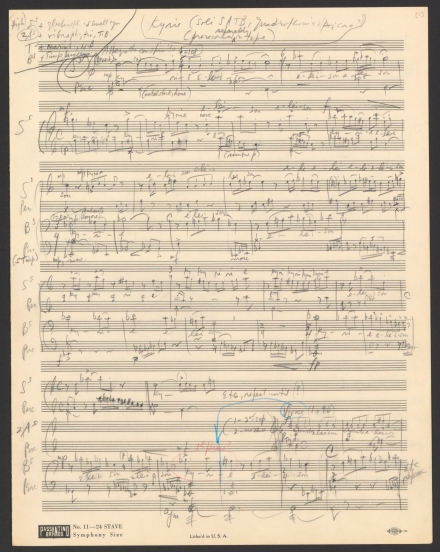

MASS: XIII. The Lord's Prayer manuscript sketch

Library of Congress Digital Archives

Library of Congress Digital Archives

MASS: Devotions Before Mass: 1. Kyrie eleison

Library of Congress Digital Archives

Library of Congress Digital Archives

Cover Art of a MASS recording by Marin Alsop and the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra

Stephen Schwartz On Working With Leonard Bernstein On MASS

Conductor Yannick Nézét-Séguin talks about Bernstein's MASS

Deutsche Grammophon

Deutsche Grammophon

Audio

Review Things Get Broken: Leonard Bernstein’s ‘MASS’ at Fifty From "Commonweal Magazine | Stephen Schloesser, SJ" 2021 Review Is ‘MASS’ Leonard Bernstein’s Best Work, or His Worst? From "The New York Times | Anthony Tommasini" 2018 Review Philadelphia Orchestra recording of Bernstein's 'MASS' is a groovy - and powerful - '70s artifact From "Philly Inquirer | Peter Dobrin" 2018 Review Review: Leonard Bernstein’s liturgy for the world From "America: The Jesuit Review | Kevin McCabe" 2018 Review Bernstein’s ‘MASS’ gets a brilliant encore, bound for TV From "The Chicago Tribune | Howard Reich" 2019 Review What Leonard Bernstein’s ‘MASS’ tells us about our church From "U.S. Catholic | Steven P. Millies" 2019 Review Leonard Bernstein’s MASS : Newer Recordings From "Musica Kaleidoskopea" 2020 Review The implosion of clericalism dramatized in Leonard Bernstein's 'MASS' From "National Catholic Reporter | Christine Schenk" 2020