Lectures/Scripts/WritingsTelevision Scripts

The Television Journey

by Schuyler G. Chapin

In a tribute essay marking the Museum of Broadcasting's 1985 Bernstein television celebration, critic Robert S. Clark wrote: "Some of the gifted among us are twice blessed: they yoke arresting talents to historic coincidences that enable them to make the most of their gifts. Leonard Bernstein was one of these: it was his—and our—good fortune that he and American television grew to maturity together."

Bernstein's television activities fell into three distinct but interconnected areas. The first were programs, like Omnibus, where he acted as teacher/interlocutor for music of many different kinds—mainstream classical, contemporary classical, jazz, musical comedy and rock. Seond were programs of his work as a composer, including his symphonies and some of his stage works—MASS, Trouble in Tahiti, Wonderful Town, and Candide, among many. Third were the over 70 programs of his appearances as a conductor, with orchestras that include the New York Philharmonic, the London Symphony, the Israel Philharmonic, the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and, especially, the Vienna Philharmonic.

Omnibus began in 1952 as the TV/Radio Workshop of the Ford Foundation. It was the first commercial television outlet for experimentation in the arts and from the beginning the program's approach was fresh and unusual. It clearly demonstrated the series' determination to make the arts come alive on television. Its most slam-bang music program took off with Bernstien on November 14, 1954, his first appearance on television, in which the then 35-year-old Maestro discussed the structure of the first movement of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony. Bernstein knew how to convey the intellectual and emotional passion of his art in a way that was accessible and stimulating to all types of viewers. His style met the middlebrow on his or her own level, without stooping. More than any musician before (or since), he understood television's potential to unlock the mysteries of music and make the home audiences care as deeply as he di dabout the glories of its expressive language.

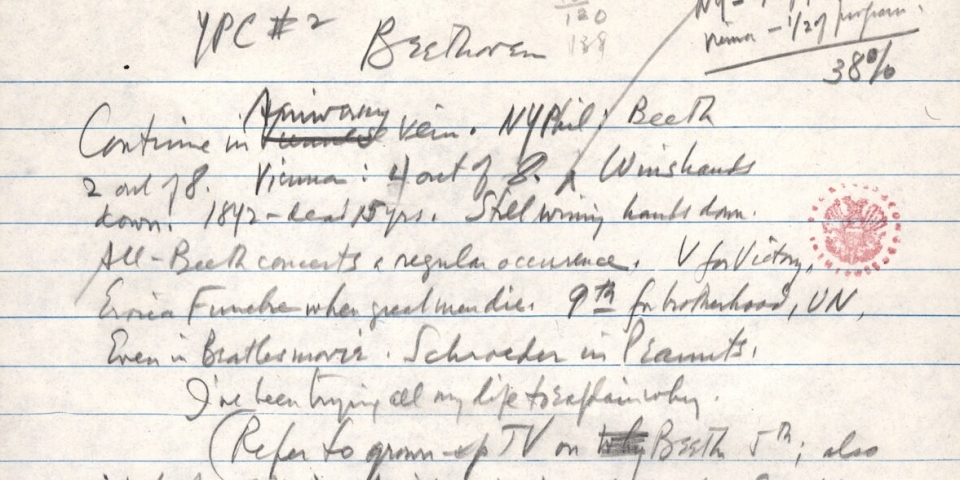

In 1957, CBS decided to feature his talents on a more regular basis by televising the New York Philharmonic's Young People's Concerts. Bernstein and director Roger Englander devised the format for the first broadcast on January 18, 1958. Recognizing that few people could match the Maestro's attention-holding powers, Englander knew it was equally important to use soe of the medium's unique resources to enhance and underscore each concert's primary theme. Not only was camerawork carefully planned in advance to coordinate with the music being played, but special visual material was inserted to illustrate key points.

Bernstein's magic with the audience at Carnegie Hall, and later at Lincoln Center's Avery Fisher Hall, and his fervor in discussing the first concert's topic of "What Does Music Mean?" came across with such effectiveness that two more Young People's broadcasts aired in the months that followed, and their successes, in turn, persuaded CBS to keep the series going.

In 1968, Bernstein stepped down as Music Director of the New York Philharmonic (but continued the Young People's Concerts until 1972.) That same year, he and I decided to create a small production company in anticipation of major technological changes in television and home video. Roger Stevens, the distinguished Broadway producer, underwrote our first venture, a video recording of Verdi's Requiem made in St. Paul's Cathedral, London, with the London Symphony Orchestra and chorus and soloists Martina Arroyo, Josephine Vesey, Placido Domingo and Ruggiero Raimondi.

Our second project was financed by CBS—a 90-minute special to celebrate Beethoven's 200th birthday. It was shortly after these successes that Unitel Film & Television Company in Munich approached us with an almost irresistable offer: to film the nine symphonies of Gustav Mahler, the four symphonies of Brahms and other works Bernstein might select with whatever orchestras he wished.

It was a fabulous and timely moment, and over the years, that association produced over 70 different musical programs that have been seen all over the world, many on PBS in the United States.

It has been said often enough that even had television not existed, Bernstein's career would still have been the most remarkable ever for a classically trained musician in America. Yet to him—and to me—it seems unarguable that his creative and recreative work remains indivisible from its television manifestations.

This article was originally published in the Spring 1992 issue of Prelude, Fugue & Riffs.

Schuyler G. Chapin, an executor and trustee of the estate of Leonard Bernstein, is currently Vice President of Worldwide Concert and Artist Activities for Steinway & Sons. He is Dean Emeritus of Columbia University's School of the Arts and former General Manager of The Metropolitan Opera.