Works Solo Instrument(s) & Orchestra Serenade (after Plato's Symposium) (1954)

"Love is simply the name for the desire and pursuit of the whole."

-Plato, The Symposium

Background

The 1950s were an extraordinarily productive decade for the young Leonard Bernstein. It was during this period that he redefined the Broadway stage with his scores for the musicals Wonderful Town (1953), Candide (1956) and West Side Story (1957). He contributed to the opera repertoire with Trouble in Tahiti (1952). He broke into Hollywood with his film score for On the Waterfront (1954), nominated for the Academy Award for "Best Music, Scoring of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture." (Although the film version of On the Town was released in 1949, On the Waterfront was Bernstein’s first -- and, as it turned out, only -- score written directly for film.) And all of this creative activity occurred while he was busily nourishing his international reputation as an orchestral conductor.

During the summer of 1954, Bernstein focused on two major compositions: his operetta-styled musical Candide, and a new orchestral piece featuring solo violin. Completed that summer, this violin concerto became the five-movement Serenade, satisfying two commitments: a much delayed commission for the Koussevitzky Foundation (1951), and the promise of a piece for violin and orchestra forhis friend, the eminent violinist, Isaac Stern. Composed in less than a year from late 1953 through August 1954, Bernstein dedicated the Serenade to the memory of his mentor, Serge Koussevitzky, and to Koussevitzky’s first wife, Natalie. Scored for solo violin, harp, string orchestra, and percussion, Serenade remains one of Bernstein’s most lyrical orchestral works.

Bernstein himself stressed that Serenade has “no literal program,” but like many of his works, including Candide, West Side Story, and the Age of Anxiety, it relates directly to literature. Bernstein has explained that the work “resulted from a rereading of Plato’s charming dialogue, The Symposium.”

Plato’s dialogue concerns itself primarily with the nature and purpose of love. The text explores love through a series of speeches in praise of Eros, delivered by some of the great thinkers of Athens at a symposium, which in ancient Greece meant, quite simply, a drinking party.

According to the composer, “The music, like the dialogue, is a series of related statements in praise of love, and generally follows the Platonic form through the succession of speakers at the banquet.” That is, each successive speaker takes as a starting point the virtues or deficiencies of the previous speaker's remarks. Analogously, the music introduces new ideas through expansion or refinement of earlier elements from previous movements in a process that longtime Bernstein music advisor Jack Gottlieb called “melodic concatenation.”

The musical relationship, according to Bernstein, “does not depend on common thematic material, but rather on a system whereby each movement evolves out of elements in the preceding one.” Specifically, this concept of evolution and transformation is associated with the opening theme presented by the solo violin: its intervals and contours are constantly reappearing and examined from new angles and in new contexts throughout the work. Thus, Bernstein has derived from Plato a model to relate the most basic elements of a large-scale work through a process whereby variations are composed through the elaboration of existing elements.”

Bernstein was always sensitive to the audience’s reception of his “funny modern music,” as Bernstein referred to the Serenade in a letter to his wife Felicia in 1955. Nonetheless, his Serenade owes much to Igor Stravinsky who, in scores such as Oedipus Rex (1927), Apollon Musagète (1928), Persephone (1933), and Orpheus (1947), demonstrated an interest in Greek archetypes and themes from Classical literature and mythology. This became a trend in all of the arts. Pablo Picasso developed an interest in Greek subjects, as did the young choreographer George Balanchine. In an interview with his future biographer Humphrey Burton in 1986, Bernstein remarked that the piece was “originally called Symposium [but] I was dissuaded from that title because people said it sounded so academic. I now regret that. I wish I had retained the title so people would know what it is based on… It’s one of Plato’s shortest dialogues and it’s on the subject of love. It’s seven speeches, at a banquet, after-dinner speeches so to speak. By Aristophanes, by Agathon, by Socrates and himself… it’s really a love piece.”

Literary Framework

On August 8, 1954, the day after completing his score, Bernstein wrote the following descriptions for each movement as a suggested series of "guideposts" for the listener:

I. Phaedrus; Pausanias (Lento; Allegro marcato). Phaedrus opens the symposium with a lyrical oration in praise of Eros, the god of love. (Fugato, begun by the solo violin.) Pausanias continues by describing the duality of the lover as compared with the beloved. This is expressed in a classical sonata-allegro, based on the material of the opening fugato.

[The second theme of this sonata movement incorporates disjunct grace-note figures and dissonant intervals in the elegant solo violin part.]

II. Aristophanes (Allegretto). Aristophanes does not play the role of clown in this dialogue, but instead that of the bedtime-storyteller, invoking the fairy-tale mythology of love. The atmosphere is one of quiet charm.

[Aristophanes sees love as satisfying a basic human need. Much of the musical material derives from the grace-note theme of the first movement. The middle section of this movement incorporates a melody for the lower strings (marked “singing”) played in close canon.]

III. Eryximachus (Presto). The physician speaks of bodily harmony as a scientific model for the workings of love-patterns. This is an extremely short fugato-scherzo, born of a blend of mystery and humor.

[This section contains music that corresponds thematically to the canon of the previous movement, Aristophanes]

IV. Agathon (Adagio). Perhaps the most moving speech of the dialogue, Agathon's panegyric embraces all aspects of love's powers, charms and functions. This movement is a simple three-part song.

V. Socrates; Alcibiades (Molto tenuto; Allegro molto vivace). Socrates describes his visit to the seer Diotima, quoting her speech on the demonology of love. Love as a daemon is Socrates' image for the profundity of love; and his seniority adds to the feeling of didactic soberness in an otherwise pleasant and convivial after-dinner discussion. This is a slow introduction of greater weight than any of the preceding movements, and serves as a highly developed reprise of the middle section of the Agathon movement, thus suggesting a hidden sonata-form. The famous interruption by Alcibiades and his band of drunken revelers ushers in the Allegro, which is an extended rondo ranging in spirit from agitation through jig-like dance music to joyful celebration. If there is a hint of jazz in the celebration, I hope it will not be taken as anachronistic Greek party-music, but rather the natural expression of a contemporary American composer imbued with the spirit of that timeless dinner party.

[Speaking through the voice of Diotima, Socrates proposes the notion that the most virtuous form of love is the love for wisdom (philosophy).]

Despite this correlation between the music and the text, Bernstein biographer Humphrey Burton suggests that the composer introduced the Platonic connection later in the compositional process; a comparison of The Symposium and Serenade reveals discrepancies in the arrangement of the speakers and their underlying emotional character. For example, in Plato, Socrates has the most important and lengthy speech, while in Serenade, the fourth movement of Agathon contains the most weighty music. It seems likely that Bernstein superimposed Plato’s episodes over a fully developed work. It is also possible that Bernstein decided upon the name Serenade well into the work’s development: in the months preceding its completion, Bernstein refers frequently to an unnamed "concerto."

Also incorporated into Serenade are several quotations from some of Bernstein’s solo piano pieces which he named “Five Anniversaries,” short works dedicated to close friends as birthday gifts or memorial tributes. Weaving these musically intimate compositions (in particular: For Elizabeth Rudolf, For Lukas Foss, For Elizabeth B. Ehrman, and For Sandy Gelhorn) into the fabric of this concerto seems particularly appropriate, given its focus on the nature of human relationships.

In the summer of 1954, in a letter to the composer William Schuman, Bernstein wrote: I've finished the Serenade.... and it looks awfully pretty on paper at least. The Italian critics will hate it; but I like it a lot.” Despite its serious intentions, Serenade is as diverting as it is illuminating. Biographer Burton observed that the work, “can also be perceived as a portrait of Bernstein himself: grand and noble in the first movement, childlike in the second, boisterous and playful in the third, serenely calm and tender in the fourth, a doom-laden prophet and then a jazzy iconoclast in the finale.”

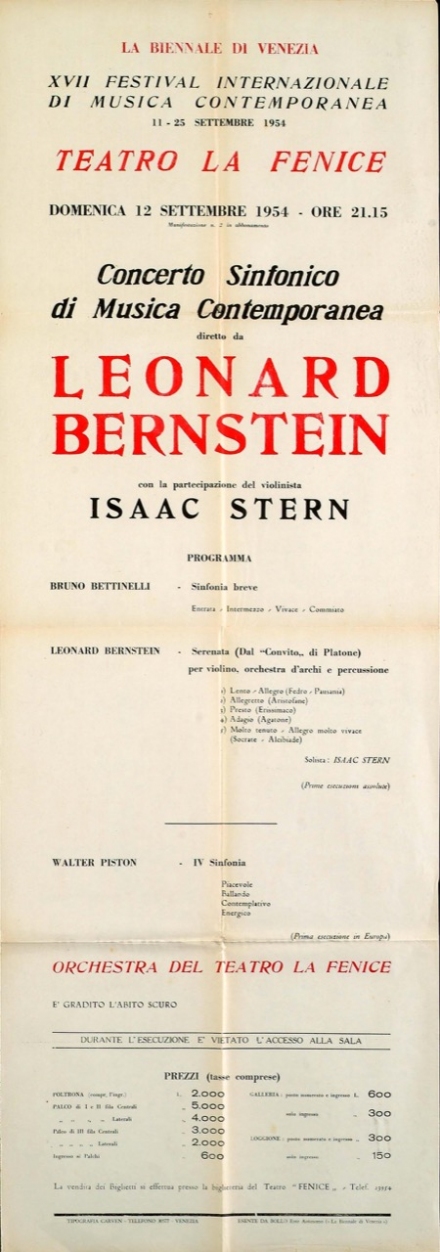

Isaac Stern premiered Serenade at the Teatro La Fenice in Venice, September 1954, with the composer conducting the Orchestra Del Teatro La Fenice . Bernstein himself, in a cable to his wife Felicia exclaimed, “Isaac plays the Serenade like an angel. If it all goes well tomorrow it should be a knockout.”

Serenade was only one triumph during a flurry of major successes during this period in Bernstein’s life. The Broadway opening of Wonderful Town in 1953 directly preceded it. The first performance of Serenade took place just two weeks after the premiere of Bernstein’s film score to On the Waterfront. The celebrated “Omnibus” telecasts began shortly afterward, in November 1954, while 1955 saw the European premiere of Wonderful Town; the birth of his second child, Alexander; and the premiere of Symphonic Suite from On The Waterfront. By December 1, 1956, he would also sign his first long-term contract with Columbia Records; would earn a post as one of the two principal conductors (along with Dimitri Mitropoulos) of the New York Philharmonic 1957-58 season; and, finally, would witness the premiere of Candide on Broadway. Within a year after the opening of Candide, the curtain would go up on West Side Story. Heralded by Marc Blitzstein as “the finest work you ever wrote,” Serenade has become a staple of the violin repertoire, with such notable soloists performing the work as Gidon Kremer, Joshua Bell, and Midori. This remarkable piece confirms Bernstein's authority as a composer of symphonic music, and helped define what is possibly the most varied and storied period of the composer's life.

LB100

Throughout the Leonard Bernstein Centennial, in a particularly notable expression of enthusiasm during the celebrations, Serenade had 276 performances across 6 continents (including Antarctica!), by 139 orchestras, featuring 80 accomplished violin soloists. According to Bachtrack.com’s 2018 statistical performance survey, Leonard Bernstein was the third-most played composer for the year, alongside Beethoven, Mozart, Bach, and Brahms, taking a top spot among the perpetual greats. Bachtrack also reported, that four of the five most-played concert works in 2018 were Bernstein Compositions, with Serenade holding the number 3 spot behind Symphonic Dances from West Side Story and Overture to Candide. In addition, as part of The Royal Ballet's Bernstein Celebration, a triple bill of new ballets set to Bernstein's music, choreographer Christopher Wheeldon's Corybantic Games, set to Serenade, was screened to theaters throughout Europe, Asia, and Australia, and later released on DVD.

*Music by Leonard Bernstein. ©1956, renewed

Gidon Kremer, violin. Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Leonard Bernstein.

℗1979 Polydor International GmbH, Hamburg. 447 957-2.

Related Works

Sonata for Violin

Details

To perform Serenade, please contact Boosey & Hawkes. For general licensing inquiries, click here.

To purchase the sheet music for Serenade, please visit our store.

Media

Anselm Feuerbach's

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

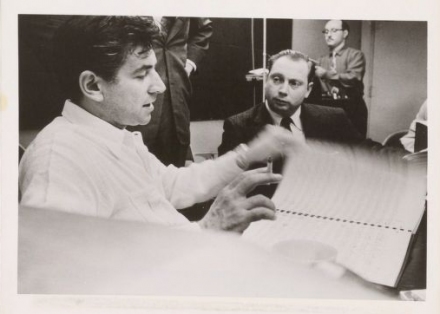

Leonard Bernstein and Isaac Stern in Venice, premier of Serenade, September 1954

Library of Congress Digital Archives

Library of Congress Digital Archives

Leonard Bernstein and Isaac Stern, recording session for Serenade, 1955.

Library of Congress Digital Archives

Library of Congress Digital Archives

Poster for 'Serenade' Premiere Performance

Teatro La Fenice Archives

Teatro La Fenice Archives

Over 75 violinists performed Serenade during the Centennial!!

Click to download list of names

Click to download list of names

"Serenade" performed in Antarctica!

Dan Zhu, violin

Dan Zhu, violin

Audio