Works Solo Instrument(s) & Orchestra Symphony No. 2: The Age of Anxiety (1949)

Background

When W.H. Auden's ambitious book-length poem The Age of Anxiety was first published in July 1947, it garnered him some of the worst reviews of his career. The Times Literary Supplement declared it "his one dull book, his one failure." For many, though, The Age of Anxiety struck a powerful chord, giving name to the cultural condition of the mid-twentieth century and allegorizing the search for faith fomented by the Second World War. T.S. Eliot lauded it as Auden's "best work to date," and the poem won the Pulitzer Prize in 1948. Within two years, it had been reprinted four times and inspired a symphony by Leonard Bernstein and a ballet by Jerome Robbins. Bernstein regarded it as "one of the most shattering examples of pure virtuosity in the history of English poetry."

"When I first read the book I was breathless," Bernstein said. "'Frock coated father framed on the wall', 'The world needs a wash and a week's rest.' It's marvelous."

Immediately after reading Auden's "fascinating and hair-raising" poem in the summer of 1947, he found " . . . the composition of a symphony based on The Age of Anxiety acquired an almost compulsive quality."

In a letter dated July 25, 1947, Bernstein's friend Richard Adams Romney was planning to send Bernstein a copy of the book and scribbled in the margins, "Why don't you try a tone poem of 'Anxiety'? The four themes—their inter-relationship, paring-off drama—etc. Might make a good thing. And you could do it!" Four days later Romney wrote again:

What do you think of the 'Anxiety' idea? There is so much musical-subtlety in it, and those various metres brought about by the different roads the couples take and their differing means of transportation, to say nothing of the moods, and the separateness that becomes Oneness under alcohol and/or libidinal urges. You mentioned it being good ballet material, yes, but I think, first, it should be composed as music by itself and therefore protect it from being too obvious program music, and then if some clever choreographer can put the musical composition to work, with what added quality good music may give to the themes and material, well and good. I would rather have 'it' in the concert hall, where it can be less 'handled' than in the ballet school where many different talents brush it up. It's too good a thing for many hands.

The letters were both persuasive and prescient. The Age of Anxiety explored a theme that Bernstein was repeatedly drawn to in his compositional career: as he described it, "The essential line of the poem (and of the music) is the record of our difficult and problematical search for faith." Identifying strongly with the poem, he chose to write his symphony for piano and orchestra, noting that "the pianist provides an almost autobiographical protagonist" in the quest for meaning and faith. Just as the friend insisted should happen, Bernstein wrote his symphony, then the score was "put to a work" by a "clever choreographer", Jerome Robbins.

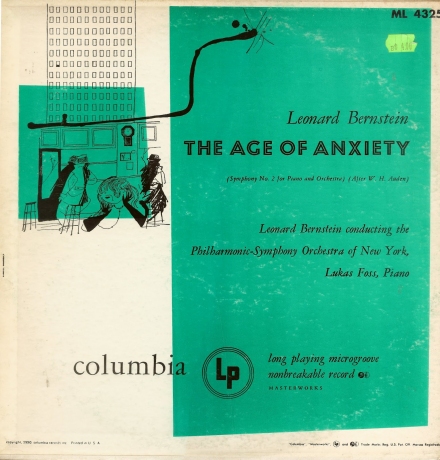

Bernstein's long-time mentor Serge Koussevitzky commissioned the symphony, and The Age of Anxiety premiered on April 8, 1949, with Koussevitzky conducting the Boston Symphony and Bernstein playing the piano solo. Bernstein dedicated the work "in tribute" to Koussevitzky, who was completing his twenty-five-year tenure in Boston; a repeat performance was given at Tanglewood that summer. In February 1950, Columbia Records recorded The Age of Anxiety with Bernstein conducting the New York Philharmonic and Lukas Foss as soloist; the same month, Jerome Robbins's new work (unfortunately now lost) for the New York City Ballet premiered at City Center.

The 80-page poem follows four lonely strangers who meet in a wartime New York bar and spend the evening ruminating on their lives and the human condition. Subtitled "a baroque eclogue" (a pastoral poem in dialog form), the characters speak mostly in long soliloquies of alliterative tetrameter, with little distinction among the individual voices.

It is divided into six sections: a "Prologue," which introduces three men and a woman, Malin, Quant, Emble, and Rosetta; "The Seven Ages," during which they gather in a booth over drinks and talk, dividing existence into seven ages from infancy to death; "The Seven Stages," in which, semi-intoxicated, they go on a symbolic dream-quest, searching for "that state of prehistoric happiness"; "The Dirge," a lament on the loss of a guiding father figure, the "colossal dad"; "The Masque," a late-night party at Rosetta's apartment where love is kindled between Rosetta and Emble but fails to develop; and an "Epilogue," wherein dawn breaks and they each return to their everyday lives, alone.

Bernstein used Auden's six section titles for the movements, masterfully mirroring the moods and events of the poem, which he described in detail in his program notes for the premiere. In "The Prologue," two clarinets engage in a lonely, pianissimo duet, one overlapping and echoing the other, followed by a long descending scale on the flute, which, Bernstein explained, "acts as a bridge into the realm of the unconscious, where most of the poem takes place." "The Seven Ages" begins with a piano solo, followed by a series of variations in which "each variation seizes upon some feature of the preceding one and develops it." Continuing with more variations in a broad range of moods and textures, the symbolic odyssey of "The Seven Stages" leads to "a hectic, though indecisive, close."

Part Two begins with "The Dirge," which "employs, in a harmonic way, a twelve-tone row out of which the main theme evolves. There is a contrasting middle section of almost Brahmsian romanticism, in which can be felt the self-indulgent, almost negative, aspect of this strangely pompous lamentation." Next, the desperate late-night party of "The Masque" "is a kind of scherzo for piano and percussion alone… in which a kind of fantastic piano-jazz is employed, by turns nervous, sentimental, self-satisfied, vociferous." When the orchestra joins in for four bars of "hectic jazz," the "traumatized" piano protagonist stops playing, effecting "a kind of separation of the self from the guilt of escapist living," and "is free again to examine what is left beneath the emptiness." In "The Epilogue," the melancholy strings finally join the winds' repeated statements of "something pure," leading to "a positive statement of the newly-recognized faith." The piano-protagonist remains a detached observer until the very end, when he plays a single chord, symbolizing the unity of man and God.

In the same program note, Bernstein admits his astonishment at "the extent to which the programmaticism of this work has been carried":

I had not planned a "meaningful" work, at least not in the sense of a piece whose meaning relied on details of programmatic implication. I was merely writing a symphony inspired by a poem and following the general form of that poem. Yet, when each section was finished I discovered, upon re-reading, detail after detail of programmatic relation to the poem—details that had "written themselves", wholly unplanned and unconscious…. If the charge of "theatricality" in a symphonic work is a valid one, I am willing to plead guilty. I have a deep suspicion that every work I write, for whatever medium, is really theatre music in some way.

Bernstein had rushed to complete the "Epilogue" movement, finishing it only three weeks before the premiere. Never satisfied with it, in 1965 he decided to make a revision, explaining, "In the years that have passed since 1949, I have reevaluated my attempt to mirror Auden's literary images in so literal a way. It seems to me to have succeeded least well in the finale, where the non-participation of the solo piano did not so much convey the intended "detachment" as rob the soloist of his concertante function. With this in mind, I have revised the finale so as to include the solo pianist, even providing him with a final burst of cadenza before the coda. I am now satisfied that the work is in its final form."

Later in his life, when asked if he thought it was important for listeners to have read the poem, Bernstein replied, "At the time I wrote it. I thought it was absolutely necessary; the poem and the Symphony were mutually integral. That's why I stuck so literally to the form of the poem. But now I don't think so. The Symphony has acquired a life of its own." Auden, who never cared for ballet, reportedly especially hated this one. Certainly, of the three works titled "The Age of Anxiety"—poem, symphony, and ballet—Bernstein's symphony has proved to be the most enduring.

LB100

Throughout the Leonard Bernstein Centennial, Bernstein’s three symphonies saw a particularly noteworthy increase in performances, with Symphony No. 2: Age of Anxiety for solo piano and orchestra receiving 183 performances by 85 orchestras and 50 pianists, in 28 countries across Asia, Australia, Europe, and North and South America. Leading orchestras that championed all three symphonies during the Centennial include the New York Philharmonic, Shanghai Symphony Orchestra, Real Orquesta Sinfonica de Sevilla, and Orchestra dell'Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia. The latter’s recording of the symphonies under the baton of Antonio Pappano garnered critical acclaim.

Related Works

Symphony No. 1: Jeremiah

Symphony No. 3: Kaddish

Details

Commissioned by the Koussevitzky Foundation

Orchestra part reduced for a second piano by Leo Smit

To perform Symphony No. 2: The Age of Anxiety, please contact Boosey & Hawkes. For general licensing inquiries, click here.

To purchase sheet music for Symphony No. 2: The Age of Anxiety, please visit the store.

Media

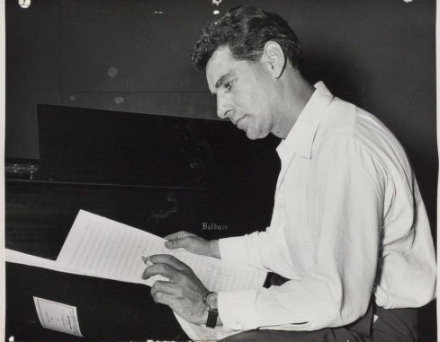

Leonard Bernstein with his score for Age of Anxiety after a session at Tanglewood, August, 1949

Library of Congress Digital Archives

Library of Congress Digital Archives

Leonard Bernstein and Serge Koussevitzky, premier of Age of Anxiety

Library of Congress Digital Archives

Library of Congress Digital Archives

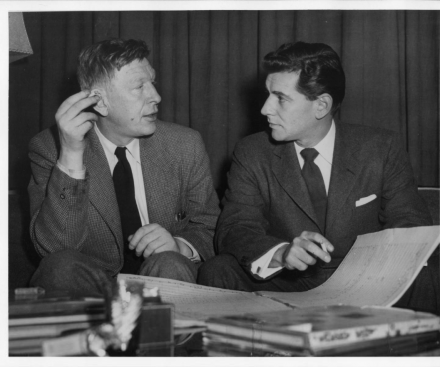

W.H. Auden and Leonard Bernstein discuss Bernstein's 'Age of Anxiety' at Bernstein's apartment

Photo by Ben Greenhaus. Courtesy of the Boston Symphony Orchestra Archives.

Photo by Ben Greenhaus. Courtesy of the Boston Symphony Orchestra Archives.

Bernstein: Symphony No. 2: The Age of Anxiety - Part II. The Masque

© 1986 Unitel / © 2008 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH, Hamburg

© 1986 Unitel / © 2008 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH, Hamburg