AboutHumanitarianAn Artist's Response to Violence

An Artist's Response to Violence

by Christopher Buchenholz

November 22, 1963 began as an ordinary Friday. Leonard Bernstein, Music Director of the New York Philharmonic, was at Philharmonic Hall in a script meeting with Jack Gottlieb and producer Roger Englander for an episode of the New York Philharmonic Young People’s Concerts, scheduled to be broadcast the next day. Also present at the meeting were Englander’s assistants Elizabeth “Candy” Finkler, John Corigliano and Mary Rodgers. The show was to be an episode of Young Performers, featuring Heidi Lehwalder (harp), Weldon Berry (clarinet), Amos Eisenberg (flute), Shulamit Ran (piano), Stephen Kates (cello), Pedro Calderon, and Zdenek Kosler (conductors).

In the office next door, Howard Keresey, the Philharmonic librarian, heard a news report of the shooting and immediately called in Gottlieb. Behind the closed door of the meeting room, they could hear Gottlieb say, “Shot! What do you mean shot? Shot dead?” Bernstein tried to maintain order in the meeting by urging his staff, “We must go on...life goes on,” but within minutes he realized, “we can’t go on.” According to Bernstein, everyone then “huddled around the radio to learn whether the shot had been fatal.”

George Szell was scheduled to conduct an all-Beethoven program at an afternoon subscription concert. The concert had already commenced when the call came through with news of the death of President Kennedy. Immediately after Beethoven’s Leonore Overture No. 3, the Orchestra’s manager, Carlos Moseley walked on stage to convey the tragic news to the audience. George Szell led the audience in a moment of silence and the rest of the program was cancelled. Bernstein's staff rescheduled Saturday’s Young People’s Concert for December 23.

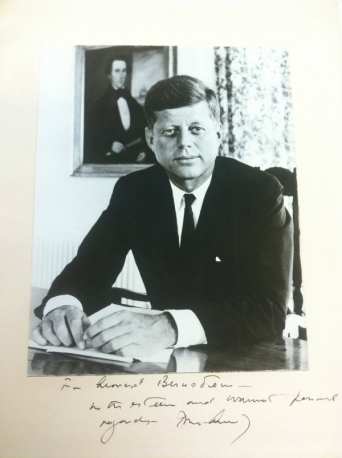

According to Bernstein biographer Humphrey Burton, “Bernstein saw Kennedy as a leader with outstanding intellectual gifts and a sympathy for the arts. Kennedy recognized Bernstein had something of his own inspirational qualities and speed at grasping issues, as well as a passion for promoting the arts.” Bernstein said of Kennedy, “Of all the political men that I have ever met, [he] was certainly the most moving and compassionate and lovable.” The newly elected President selected Bernstein to compose and conduct a fanfare for Kennedy’s Inaugural Gala. Bernstein soon became a regular presence in the Kennedy White House. In turn, the President and his wife attended the opening night of Candide. Bernstein kept a signed photograph of the President on his piano.

In the day after Kennedy’s assassination, as the country grappled with the loss of their charismatic leader, and Bernstein mourned for his close friend, CBS President Frank Stanton called to ask whether Bernstein would create a memorial program for the following day. The news had come that Eugene Ormandy intended to lead the Philadelphia Orchestra in Verdi’s Requiem, the ostensibly obvious choice for a memorial concert. Roger Englander and Carlos Mosely were discussing the possibility of performing excerpts from the Verdi, but Candy Finkler objected to the idea, admonishing, “You can’t do that, it’s like performing the best of Hamlet.” They settled on Brahms’ Deutsches Requiem, and Finkler immediately called Patelson’s music store, across the street from Carnegie Hall, to secure the score and parts. Finkler and staff assembled a crew, and booked the expansive CBS-TV Studio 61 on East 76th Street (also known as the Monroe Theater).

The New York Philharmonic, however, had already been rehearsing Mahler’s Second Symphony for a future program. On Sunday, November 24, two days after the assassination, Leonard Bernstein conducted the New York Philharmonic and the Schola Cantorum of New York in a nationally televised JFK memorial featuring Mahler's Resurrection Symphony-- not the Brahms Requiem. The performance featured soloists Lucina Amara (soprano), and Jennie Tourel (mezzo-soprano). This was the first televised performance of the complete symphony. Indeed, Mahler’s music had never been performed for such an event. The more common practice would have been to perform a requiem, or, as George Szell did for the remaining Philharmonic concerts that weekend — replace the overture with the funeral march from Beethoven's Symphony No. 3, Eroica and ask that the audience members not applaud after the movement’s final bars.

On the evening of Monday, November 25, the United Jewish Appeal of Greater New York held its annual fundraising event, the twenty-fifth “Night of Stars” at Madison Square Garden. The event was part of the UJA’s annual fundraising campaign for aid on behalf of Israel. Vice-President Lyndon B. Johnson was originally scheduled to speak, but cancelled, and the event instead became a memorial to the slain President. Bernstein was there, as were violinist Isaac Stern, soprano Eleanor Steber, and 18,000 distinguished attendees. The President of the New York Board of Rabbis spoke, and Bernstein had prepared remarks. These were his words:

My dear friends:

Last night the New York Philharmonic and I performed Mahler’s Second Symphony-- The Resurrection-- in tribute to the memory of our beloved late President. There were those who asked: Why the Resurrection Symphony, with its visionary concept of hope and triumph over worldly pain, instead of a Requiem, or the customary Funeral March from the Eroica? Why indeed? We played the Mahler symphony not only in terms of resurrection for the soul of one we love, but also for the resurrection of hope in all of us who mourn him. In spite of our shock, our shame, and our despair at the diminution of man that follows from this death, we must somehow gather strength for the increase of man, strength to go on striving for those goals he cherished. In mourning him, we must be worthy of him.

I know of no musician in this country who did not love John F. Kennedy. American artists have for three years looked to the White House with unaccustomed confidence and warmth. We loved him for the honor in which he held art, in which he held every creative impulse of the human mind, whether it was expressed in words, or notes, or paints, or mathematical symbols. This reverence for the life of the mind was apparent even in his last speech, which he was to have made a few hours after his death. He was to have said: “America’s leadership must be guided by learning and reason.” Learning and reason: precisely the two elements that were necessarily missing from the mind of anyone who could have fired that impossible bullet. Learning and reason: the two basic precepts of all Judaistic tradition, the twin sources from which every Jewish mind from Abraham and Moses to Freud and Einstein has drawn its living power. Learning and Reason: the motto we here tonight must continue to uphold with redoubled tenacity, and must continue, at any price, to make the basis of all our actions.

It is obvious that the grievous nature of our loss is immensely aggravated by the element of violence involved in it. And where does this violence spring from? From ignorance and hatred-- the exact antonyms of Learning and Reason. Learning and Reason: those two words of John Kennedy’s were not uttered in time to save his own life; but every man can pick them up where they fell, and make them part of himself, the seed of that rational intelligence without which our world can no longer survive. This must be the mission of every man of goodwill: to insist, unflaggingly, at risk of becoming a repetitive bore, but to insist on the achievement of a world in which the mind will have triumphed over violence.

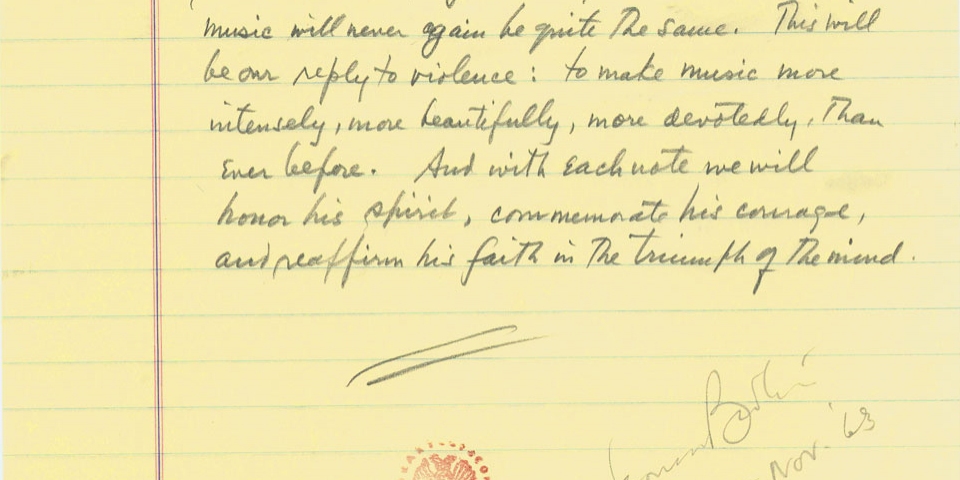

We musicians, like everyone else, are numb with sorrow at this murder, and with rage at the senselessness of the crime. But this sorrow and rage will not inflame us to seek retribution; rather they will inflame our art. Our music will never again be quite the same. This will be our reply to violence: to make music more intensely, more beautifully, more devotedly than ever before. And with each note we will honor the spirit of John Kennedy, commemorate his courage, and reaffirm his faith in the Triumph of the Mind.

The following month, on December 10, 1963 in Tel Aviv, Bernstein’s next major work, the Kaddish Symphony, had its world premiere performance with the Israel Philharmonic. Bernstein dedicated his Symphony: “To the beloved memory of John F. Kennedy.” The American premiere occurred on January 10, 1964, with Charles Munch and the Boston Symphony Orchestra at Symphony Hall, near Kennedy’s hometown of Brookline Massachusetts.

Ever since Bernstein’s riveting tribute to JFK, Mahler’s symphonies have become a musical symbol for national mourning. On June 8, 1968, Bernstein conducted the Adagietto from Mahler's Symphony No. 5 at JFK’s brother Robert’s funeral at Saint Patrick’s Cathedral. Pierre Boulez also performed the Adagietto on March 28, 1969, the day President Dwight D. Eisenhower died. On September 10, 2011, conductor Alan Gilbert directed the New York Philharmonic in a memorial of the 9/11 terrorist attacks with Mahler's Second Symphony, the same piece performed by Bernstein in memory of JFK.

Bernstein’s powerful antiphon against hatred remained unknown until 1982 when it was published in “Findings,” a personal self-portrait containing essays, letters, and other writings on a variety of subjects. John F. Kennedy was a true champion of the arts. In the wake of his murder, many artists and musicians, poets and thinkers have searched for meaning in the shadow of tragedy. For many, Bernstein’s “reply to violence” has been a beacon of hope for those in distress. After the attacks on The World Trade Center and the Pentagon on September 11, 2001, during the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, in the wake of the Newtown massacre and the Boston Marathon bombings, people have turned to Bernstein’s words as a source of comfort and strength in the face of unimaginable pain and loss. For Bernstein, as for Kennedy, “Learning and Reason” were the appropriate responses, the appropriate antidote to ignorance and hatred, and are the true instruments of peace.

"Tribute to John F. Kennedy" printed in FINDINGS by Leonard Bernstein © 1982, Leonard Bernstein