AboutHumanitarianDisarmament Activist

Photo Credit: James Lightner

Photo Credit: James Lightner

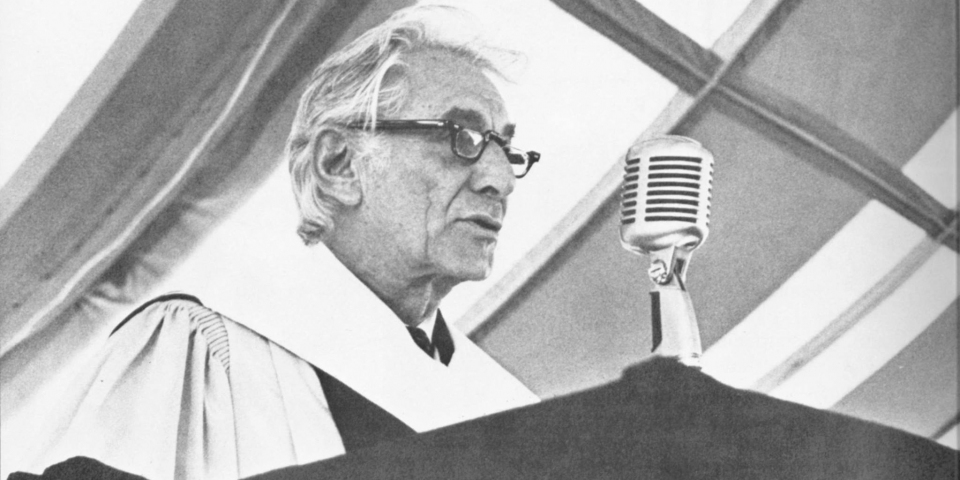

Commencement Speech at Johns Hopkins

May 30, 1980

President Muller, worthy Deans, learned faculty, reverend clergy:

I thank you most sincerely for this honor. In accepting it, I am reminded of the words of your first president, Daniel Gilman, who said, at the dedication of the Medical School, that a university "misses its aim if it produces learned pedants, or simple artisans or cunning sophists, or pretentious practitioners…Its purpose is not so much to impart knowledge as to whet the appetite…."

I should like to take off from there, and, with your permission, speak now directly to the graduating body itself.

My dear young friends:

The notes for these upcoming remarks were made on a Sunday morning a week or so ago – a cold, rainy Sunday morning. I had just put aside the Sunday New York Times – or rather, the little of it could read without ruining my breakfast – and was staring alternatively at the gray outdoors and the blank page before me, trying to digest the unrelentingly hopeless reports I had been reading of this, our world; then trying the find something in them that could be the basis for this commencement address; then trying to forget them entirely, so that my mind might be free to invent something hopeful to say at this happy band of departing graduates. No such luck, to quote my mother. I tell you all this only in case what I do say should, by chance, reflect the chill of that gray morning, and of its newspaper.

Now, you and I know that the good, gray lady, pessimism, however elegant she may be, has no business intruding upon a commencement speech, however inelegant it may be. I am here to deliver a Charge to the Graduates, Mandatum Alumnibus, and send them charging into their future with banners raised. Hail optimism; be with us, Leibnitz! No such luck.

And so, that Sunday morning, I began to make these notes, putting myself into your place. What do those seniors and graduate students want to hear from me? That you are brilliantly educated; the world is yours, go forth and take it? You are far too sophisticated for such bromides. Or do you await a high moral tone, inciting your acquired idealism to triumph over your native materialism? No, this is not a sermon, said I that Sunday morning, nor shall I come as a preacher. But perhaps I might come as an artist, the musician I am, to share with you something of what goes on in an artist's head and heart when confronted with what we blithely call reality.

Two World Wars ago, the great Irish poet Yeats observed a reality remarkably like our own. "Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold," he intoned in that brief but shattering poem called "The Second Coming." "The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere / The ceremony of innocence is drowned;" – and then come the two lines that make one's flesh crawl, because they sound as though they were written yesterday;

The best lack all connection, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Most uncomfortably familiar. And how did Yeats respond to this chilling picture he himself had drawn? Like all artists, he responded with a vision, an equally chilling vision of a pitiless redemption; I'm sure you all remember that image of the rough beast slouching toward Bethlehem to be born. Who can forget it? And that image, that vision, alarms and alerts us today at least as strongly as it did its readers sixty years ago. But at the same time this poem comforts us and strengthens our faith by its very existence, by its perfect beauty, its aesthetic Inhalt. Like all great art, it tells us that we have guardians out there – artists, the prophets among us, scanning horizons we cannot see. Yeats looked beyond reality and beheld an enduring fantasy.

Every artist copes with reality by means of his fantasy. Fantasy, better known as imagination, is his greatest treasure, his basic equipment for life. And since his work is his life, his fantasy is constantly in play. He dreams life. Psychologists tell us that a child's imagination reaches its peak at the age of six or seven, then is gradually inhibited, diminished to confirm with the attitudes of his elders – that is, reality. Alas. Perhaps what distinguishes artists from regular folks is that for whatever reasons, their imaginative drive is less inhibited; they have retained in adulthood more of that five-year-old's fantasy than others have. This is not to say that an artist is the childlike madman the old romantic traditions have made him out to be; he is usually capable of brushing his teeth, keeping track of his love life, or counting his change in a taxicab. When I speak of his fantasy I am not suggesting a constant state of abstraction, but rather the continuous imaginative powers that inform his creative acts as well as his reactions to the world around him. And out of that creativity and those imaginative reactions come not idle dreams, but truths – all those abiding truth-formations and constellations that nourish us, from Dante to Joyce, from Bach to the Beatles, from Praxiteles to Picasso. Apropos Picasso, last week I visited that staggering Picasso retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and I was overwhelmed by the display of sheer imagination, of fantasy; of the sense of play, the joyful switching of styles, the constant freedom to think new, take chances – to have fun, in the deepest sense of the word. It is a great lesson, not only in art, but in living, because it is such a stimulus and exhortation for every one of us who views it to refresh our thinking and our attitudes, to cultivate our fantasy.

Which brings me to the salient point: The gift of the imagination is by no means an exclusive property of an artist; it is a gift we all share; to some degree or other all of us, all of you, are endowed with the powers of fantasy. The dullest of dullards among us has the gift of dreams at night – visions and yearnings and hopes. Everyone can also think; it is the quality of thought that makes the difference – not just the quality of logical thinking, but of imaginative thinking. And our greatest thinkers, those who have radically changed our world, have always arrived at their truths by dreaming them; they are the first fantasized, and only then subjected to proof. This is certainly true of Plato and Kant, of Moses and Buddha, of Pythagoras and Copernicus and, yes, Marx and Freud and, more recently, Albert Einstein, who always insisted that imagination is more important than knowledge. How often he spoke of having dreamed his Unified Field Theory and his Principle of Relativity – intuiting them, and then, high on the inspiration, plunging into the perspiration of working them out to be provable, and therefore true.

But what is true? Is Newtonian physics any less true for having been superseded by Einsteinian physics? No more than Wittgenstein has knocked Plato out of your philosophy courses. The notion that the earth is flat was never a truth; it was merely a notion. That the earth is round is a proven truth which may one day be modified by some new concept of roundness, but the truth will remain, modified or not. Truths are forever; that's why they are so hard to come by. Plato promulgated absolute truths; Einstein relative ones. Both were right. Both conceived their visions in high fantasy. And even Hegel, that stern dialectician, said that truth is a Bacchanalian revel, where not a member is sober. Well said, old Georg Wilhelm Friedrich; we hear you loud and clear. To search for truth, one has to be drunk with imagination.

Now, what has all this to do with you, or with the grim realities we face each day? It has everything to do with you, because you are the generation of hope. We are counting on you – on your imagination – to find new truths: true answers, not merely stopgaps, to the abounding stalemates that surround us. Buy why us, you ask? Why are you laying this very heavy number on our generation? I'll try to tell you why.

The generation that preceded yours has been a pretty passive one, and no wonder. It was the first generation in all history to be born into a nuclear war, the first people ever to have had to accept the bomb as an axiom of life. There it is; the world is qualitatively changed; behold the Hiroshima generation. You can understand how this can have caused a profound passivity, a turning-inward to self-interest, a philosophy of "take as much as you can while there's still time." And, of course, this so-called "me" generation was strongly reinforced in its passivistic philosophy by the extraordinary takeover of television; it was the first generation to be reared on and chained to the TV tube, with all its promise of instant gratification, both in the commercials – instant relief, instant gorgeous hair, instant everything – and in the very phenomenon of having that gratification at your fingertips in the form of instant and varied entertainment. And add to those a third element, the enormously increased indulgence in dope, and you have a perfect recipe for passivity. The result in large measure, has been dropping out in one way or another, or else the mad rush to be fitted for that three-piece suit, as soon as possible, and then an overriding concern with making it, in the most cynically materialistic way. I don't have to tell you that neither of these consequences has produced much in the way of imaginative thinking.

But your generation is different. Oh, really? You say. We also live in a bomb-ridden world; we've also got out TV, our dope, our instant gratifications. Why, some of us have already been measured for a three-piece suit. Ah, but you are different, because you have perspective – a priceless asset; you have decades of distance from your predecessors on whom all these influences descended suddenly, together, and without warning. You are the first generation since Hiroshima that can look back and say, No – not for me. You have witnessed the laid-back thinking of your predecessors; you have grown up with Vietnam, Watergate, and all the other cautionary lessons of your two decades. Thus, you are, can be, a new and separate generation, with fresh minds, ready for new thinking – for imaginative thinking – if you allow yourselves to cultivate your fantasy.

What I am asking of you, and what you must ask yourselves, is this: Are you ready to free your minds from the constraints of narrow, conventional thinking, the rigorous dictates of a received logical positivism? Are you willing to resist being numbed into passivity by settling for the status quo? More specifically, do you have the imaginative strength to liberate yourselves from the Cold War ambiance in which the eighties have already begun – along with all its accompanying paraphernalia of ever-proliferating borders, barriers, walls, passports, racial and subnational fragmentation and refragmentation? Far too many people have begun to speak of the "Third World War" as if it were not only conceivable, but a natural inevitability. I tell you it is not conceivable, not natural, not inevitable, and all the pseudo- professional talk about rates of possible survival after nuclear attack in cities A and B or area X and Y is dangerous and foolish talk. Survival of what, how, to what end? The height of absurdity is reached in the word overkill – a subject much discussed in high places. What on earth can be the point in solemn negotiations to reduce the percentage of overkill from, say 89 to 84? or from 2 to 1, for that matter? One percent overkill is enough to extinguish the planet. And the more this useless talk goes on, the more we witness a steady proliferation of nuclear arms. The mind boggles.

What do we do with our minds when they boggle? We quickly put them to strenuous imaginative work. Mind-boggling time is the perfect moment for fantasy to take over; it's the only way to resolve a stalemate. And so, I ask you again: Are you ready to dare to free your minds from the constraints we, your elders, have imposed on you? Will you accept, as artists do, that the life of the spirit precedes and controls the life of exterior action; that the richer and more creative the life of the spirit, the healthier and more productive our society must necessarily be?

If you are ready to accept all that – and I am not saying that it's easy to do – then I must ask if you are ready to admit the ensuing corollaries, starting bravely with the toughest one of all: that war is obsolete. Our nuclear folly had rendered it obsolete, so that it now appears to be something like a bad old habit, a ritualistic, quasi-tribalistic obeisance to the arrogance of excessive nationalism, face-saving, bigotry, xenophobia, and above all, greed. Do you not find something reprehensible, even obscene, about the endless and useless stockpiling of nuclear missiles? Isn't there something radically wrong with nation-states' squandering the major portion of their wealth on military strength at the expense of schools, hospitals, libraries, vital research in medicine and energy – to say nothing of preserving the sheer livability of our planetary environment? Why are we behaving in this suicidal fashion?

Obviously, I cannot supply the kind of authoritative answers you would receive from a man of politics, economics, or sociology. Those are not my disciplines. I am an artist, and my answer must necessarily be that we do not permit our imagination to bloom. The fantasies we do act out are still the old tribalistic ones arising out of greed, lust for power, and superiority. We need desperately to cultivate new fantasies, ones that can be enacted to make this earth of ours a safe, sound, and morally well-functioning world, instead of a destruction. We are told again and again that there is food enough on this planet to supply the human race twenty times over; that there is enough water to irrigate every desert. The world is rich, nature is bountiful, we have everything we need. Why is it, then, so hard to arrive at a minimal standard below which no human being is allowed to sink? Again, we need imagination, fantasy -- new fantasies, with the passion and courage to carry them out. Only think: if all our imaginative resources currently employed in inventing new power games and bigger and better weaponry were reoriented toward disarmament, what miracles we could achieve, what new truths, what undiscovered realms of beauty!

Impossible, you say? Inconceivable to disarm without inviting annihilation? Okay. Let's invent a fantasy together, right now – and I mean a fantastic fantasy. Let's pretend that any one of us here has become President of the United States – a very imaginative President, who has suddenly taken a firm decision to disarm, completely and unilaterally. I see alarm on your faces: This crazed artist is proposing sheer madness. It can't be done: A President is not a dictator; this is a democracy. Congress would never permit it, the people would howl with wounded national pride, our allies would scream betrayal. It can't be done. But of course, it can't be done if everybody starts saying it can't be done. Let's push our imagination; remember, we're only fantasizing. Let's dare to be simplistic. All right, someone would stand up in Congress and demand that the president be impeached, declared certifiable, and locked away in a loony bin. Others would agree. But suppose – just suppose – that one or two Senators or Congressmen got the point, and recognized this mad idea as perhaps the most courageous single action in all history. And suppose that those few members of Congress happened to be hypnotically powerful orators. It just might become contagious – keep pushing that imagination button! – it just might get through to the people, who instead of howling might well stand up tall and proud to be participating in this unprecedented act of strength and heroism. There might even be those who would feel it the noblest of sacrifices – far nobler, surely, than sacrificing one's children on the field of Armageddon. And this pride and joyful courage would spread – keep pushing that button! – so that even our allies might applaud us. There is the barest possibility that it just might work.

All right; now what? Now is when we really have to push, let fantasy lead us where it will. What is your first thought? Naturally, that the Soviet Union would come plowing in and take us over. But would they really? What would they do with us; why would they want to assume responsibility and administration of so huge, complex, and problematical a society as ours? And in English, yes! Besides, who are the Soviet Union – its leaders, its army, or its people? The only reason for the army to fight is that their leaders would have commanded them to do so; but how can they fight when there is no enemy? The hypothetical enemy has been magically whisked away, and replaced by two hundred-odd million smiling, strong, peaceful Americans. Now keep the fantasy going: the Russian people certainly don't want war; they have suffered far too much; and it is more likely that they would displace their warlike leaders, and transform their Union of Socialist Republics into a truly democratic union. And – keep going, keep going! – think of the example that would have been set for the whole world; think of the relief at no longer having to bluster and saber-rattle and save face; think of the vast new wealth now available to make life rich, beautiful, clean, sexy, thoughtful, inventive, healthful, fun! And there would be so many new things to do, to invent, to build, to try, to sell, to buy.

Well, maybe it won't work. But something in all that fantasy trip must have struck as – well, just possibly. And if one little seed or syllable of an idea may have entered one little ear in this vast assembly, where it can grow among the fertile neurons of one imaginative brain, then I could pray for no more. And at the very least you must admit that nothing I have fantasized, lunatic-artist though I may be, is actually inconceivable. After all, we did imagine it together, from beginning to end; which is a hell of a lot better than trying to imagine Armageddon, the extinction of mankind – which for this artist, at least, is indeed inconceivable. And this artist challenges you to pursue the fantasy, all your fantasies, while there is still time.

Now look what I've done: everything I said I wouldn't do. I have indeed given a Charge to this graduating body, in spite of all my good intentions; I have told you to go forth and take the world; I may even have sermonized. Forgive me: I was carried away by hope – hope in the wake of pessimism. And that hope is you, my dear young friends. May God bless you.