AboutHumanitarianRadical Chic Flap

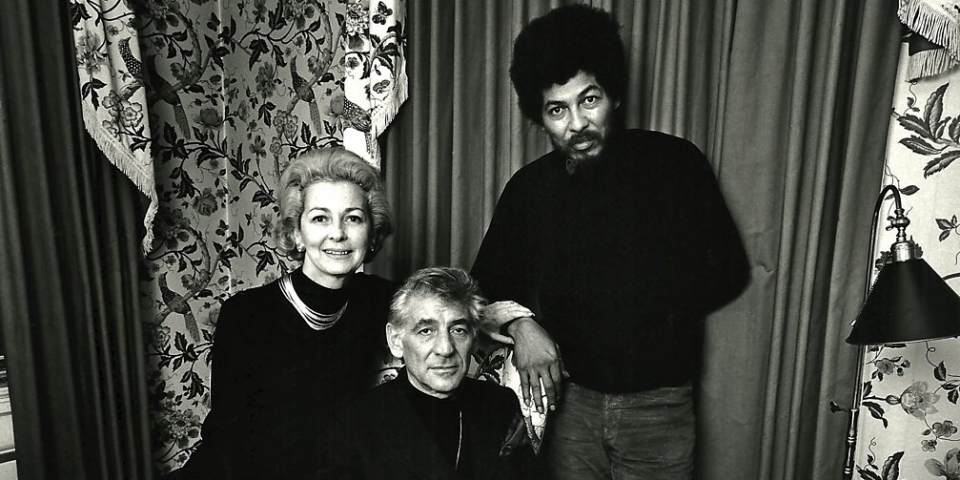

Leonard Bernstein (center), Felicia Montealegre (left) and Don Cox (standing), Field Marshal of the Black Panther Party in the Bernsteins' penthouse on Park Avenue in Manhattan, January 14, 1970. Photo by Steve Salmieri

Leonard Bernstein (center), Felicia Montealegre (left) and Don Cox (standing), Field Marshal of the Black Panther Party in the Bernsteins' penthouse on Park Avenue in Manhattan, January 14, 1970. Photo by Steve Salmieri

The Panther 21 Fundraiser and "Radical Chic"

by Kate Chisholm, with contributions from Jamie Bernstein

On the evening of January 14, 1970, Felicia Bernstein hosted approximately 90 people in the Bernsteins' home to raise funds to support the families of the "Panther 21," a group of twenty one Black Panther Party members arrested on April 2, 1969 and charged with conspiring to kill police and bomb New York police precincts, department stores, and other public buildings. The Panther 21 had been held in jail for nine months—many on bails set as high as $100,000—without a trial and without adequate resources to prepare for their defense.

The Black Panther Party, a radical, socialist organization committed to the empowerment of African Americans, was a source of anxiety for many Americans. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover called the Black Panther Party "the greatest threat to the internal security of the country." Yet to civil libertarians, the arrest of the "Panther 21" appeared to be a case of government engaging in preventive, political detention and ignoring due process. A group of concerned New Yorkers established a fund to help with legal expenses and to assist the families of the accused while the prisoners awaited trial; the gathering at the Bernstein apartment was held to raise awareness and contribute to this fund.

What was intended as a serious meeting to address a violation of civil liberties became a sorely misunderstood event that led to a media frenzy and extensive personal attacks on the Bernsteins. Years later, it was further understood to be a glaring example of FBI intrusiveness at its very worst.

In attendance at the Bernstein apartment on January 14th were numerous prominent figures in the arts and media, including Otto Preminger, Jean vanden Heuvel, Peter and Cheray Duchin, Sidney and Gail Lumet, Cynthia Phipps, Barbara Walters, Bob Silvers, Mrs. Richard Avedon, Mrs. Arthur Penn, Julie Belafonte, Peter Stone, Sheldon Harnick and Burton Lane. Also present were Black Panther Party members Robert Bay, Donald Cox and Henry Miller, as well as some wives of the accused. Members of the press were not invited to the event, but Charlotte Curtis of the New York Times and Tom Wolfe of New York Magazine somehow managed to slip in.

A social hour was followed by a meeting in the living room, in which Leon Quat, a lawyer, Donald Cox, field marshal for the Black Panthers, and Gerald Lefcourt, chief counsel for the defense, each spoke, followed by a question and answer period. Leonard Bernstein arrived late from a rehearsal of Beethoven's Fidelio and joined the discussion. At the end of the meeting, contributions were solicited, and nearly $10,000 was raised.

The following day, Charlotte Curtis reported on the fundraiser in The New York Times society section. "There they were, the Black Panthers from the ghetto and the black and white liberals from the middle, upper-middle and upper classes studying one another cautiously over the expensive furnishings, the elaborate flower arrangements, the cocktails and the silver trays of canapés." (The New York Times, January 15, 1970)

The account of the liberal elite socializing with the radical Panthers caused an immediate backlash that was further fueled by a January 16 editorial in the Times condemning the Panthers and the Bernsteins for undermining the serious efforts of those working for civil rights:

"Emergence of the Black Panthers as the romanticized darlings of the politico-cultural jet set is an affront to the majority of black Americans. ...The group therapy plus fund-raising soirée at the home of Leonard Bernstein… represents the sort of elegant slumming that degrades patrons and patronized alike. It might be dismissed as guilt-relieving fun spiked with social consciousness, except for its impact on those blacks and whites seriously working for complete equality and social justice. It mocked the memory of Martin Luther King Jr...." (The New York Times, January 16, 1970)

The same day, Mrs. Bernstein wrote a response to the Times and delivered it personally to their office — though, curiously, the Times did not publish it until several days later. She wrote:

"As a civil libertarian, I asked a number of people to my house on Jan. 14 in order to hear the lawyer and others involved with the Panther 21 discuss the problem of civil liberties as applicable to the men now awaiting trial, and to help raise funds for their legal expenses. ...It was for this deeply serious purpose that our meeting was called. The frivolous way in which it was reported as a 'fashionable' event is unworthy of The Times, and offensive to all people who are committed to humanitarian principles of justice." (The New York Times, January 21, 1970)

Felicia Bernstein was unable to stop the outcry. For the next few months, the Bernsteins received volumes of hate mail, withstood innumerable printed attacks and were harassed all spring in front of their building by picketers from the Jewish Defense League who loudly protested Bernstein's supposed "endorsement" of the anti-Zionist Panthers.

Five months later, the fundraiser was immortalized in a lengthy essay by Tom Wolfe in New York Magazine entitled, "Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny's" (June 8, 1970). Urbane, witty, and supremely derisive of Bernstein, Wolfe used the Bernstein "party" to demonstrate what he saw as a trend among the wealthy, white elite to dabble in radical social causes and hobnob with extremists in an attempt to be "chic" — hence the term coined in the title. For twenty-nine pages, Wolfe dissected every detail of the evening, from the "million-dollar chatchka look" of the apartment to the tactfully selected white servants, to portraying Bernstein as "the Great Interrupter, the Village Explainer, the champion of mental jotto" who talked "jive" with the "funky" Black Panthers.

On May 13, 1971, after an eight-month trial and only a few hours of jury deliberation, the Panther 21 defendants were acquitted on all counts—in part because it emerged that undercover informants had infiltrated the Black Panther Party and instigated the bomb plot.

Any factual retrospective on Felicia Bernstein's fundraiser in support of the Black Panthers 21's civil liberties and rights to legal representation has been consistently overwhelmed by the toxic combination of Wolfe's satire and the F.B.I.'s secret harassment campaign.

In the 1980s, parts of Bernstein's 800-page F.B.I. file were released under the Freedom of Information Act. The contents revealed that for over three decades, the F.B.I. kept extensive records on Bernstein's political activities, obsessively trying (but never succeeding) to establish that he was a member of the Communist Party. (In fact, he never was.) In the aftermath of the fundraiser for the Panther 21, the released files now made clear, the F.B.I. had engaged in a methodical undercover campaign to damage Bernstein's reputation. The angry letters and hate mail sent to the Bernsteins were orchestrated by J. Edgar Hoover's counterintelligence program. The Jewish Defense League protesters outside the apartment were heavily infiltrated by F.B.I. operatives. And the relentless assault by the press was in part instigated by the FBI's carefully placed confidential news leaks to their cooperative press contacts.

In response to these revelations, Bernstein issued the following statement:

I have substantial evidence now available to all that the F.B.I. conspired to foment hatred and violent dissension among blacks, among Jews and between blacks and Jews. My late wife and I were among many foils used for this purpose, in the context of a so-called 'party' for the Panthers in 1970 which was neither a party nor a 'radical chic' event for the Black Panther Party, but rather a civil liberties meeting for which my wife had generously offered our apartment.

The ensuing F.B.I.-inspired harassment ranged from floods of hate letters sent to me over what are now clearly fictitious signatures, thinly-veiled threats couched in anonymous letters to magazines and newspapers, editorial and reportorial diatribes in The New York Times, attempts to injure my long-standing relationship with the people of the state of Israel, plus innumerable other dirty tricks. None of these machinations has adversely affected my life or work, but they did cause a good deal of bitter unpleasantness, especially to my wife who was particularly vulnerable to smear tactics. (The New York Times, October 22, 1980)

In his unpublished collection of personal thoughts, Leonard Bernstein quotes a November 1986 New Yorker profile of music historian Nicolas Slonimsky, in which the esteemed historian cites as his bête noire "factual errors that, once born into print, refused to die, and indeed spread exponentially from one sourcebook to another, eternally. They haunted his sleep like vengeful wraiths." Leonard Bernstein wrote at the top of the page: "A Lexicon of Gripes, Whines, Clarifications". The first item on his list that follows: "Black Panthers."

Jamie Bernstein wrote,

With the "New York 21" episode, the FBI nearly succeeded in discrediting Leonard Bernstein. For a time my father's stature as a musician was overshadowed by his awful new role as object of trendy ridicule, embarrassing to his acquaintances and infuriating to his fellow Jews. Sadly, we weren't the only ones to suffer. The FBI had deliberately pitted Jews and African-Americans against each other, fanning flames of animosity and mistrust that burn to this day.

Maybe a few more people now understand what an indomitable visionary he was. All his life my father resisted the easy tendency to divide the world into Us versus Them. His embrace of humanity shines through every note of music he composed and conducted. The very existence of music, he believed, was glorious evidence of the human potential for good. That belief was the strength and soul of his lifework, and such beliefs are more powerful than any attempt to discredit them.