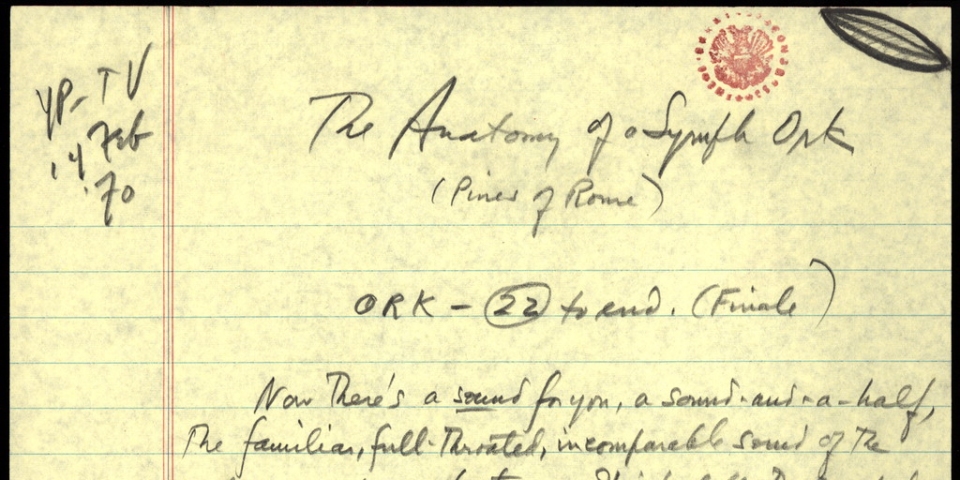

Lectures/Scripts/WritingsTelevision ScriptsYoung People's ConcertsThe Anatomy of a Symphony Orchestra

Young People's Concert

The Anatomy of a Symphony Orchestra

Written by Leonard Bernstein

Original CBS Television Network Broadcast Date: 24 May 1970

[ORCH: Last 6 Bars of Finale.]

Now there's a sound for you, that's a sound- and-a-half- the familiar, full-throated, incomparable sound of the modern symphony orchestra. It is probably the grandest sound on earth — at least among man-made noises. In all its variety and mixture and splendor. How did this sound ever come to be? How is it that this particular collection of sound-making devices have come together to achieve this grandeur?

Well, that's a long history and longer than we have time to tell on this program.

But what we can do is to show you the anatomy of this orchestra- as it exists today: we can put a sort of X-ray onto it, analyze it, dissect it, as if we were in a scientific laboratory.

And in order to do this, we've picked a piece of music that's not regarded as the greatest, like a Beethoven symphony or a Wagner opera, but which is perfect for our purposes. It's called "The Pines of Rome" by the early 20th century Italian composer, Ottorino Respighi. This famous and popular symphonic poem is one of those colorful, descriptive pieces that have been so widely imitated in movie scores and TV background music. But remember, in 1924, when Respighi wrote it, the sound film had not yet been invented so at that time the Pines was considered a pretty original and imaginative creation.

And it's still, for that matter, has quite an original sound today, - and — as I said before, it's just great for our X-ray purposes here; because it reveals the orchestra in all its different glorious aspects, and even calls for some extra instruments not normally used in a symphony orchestra. I think you're going to find it exciting.

But before we plunge into it, I'd like to prepare you for it with a very brief look into just how this massive symphony orchestra is divided; what constitutes it—and this will be our first set of X-rays in this lab session. Now usually the elements of the orchestra are explained and demonstrated in terms of families, the families of instruments, where you inevitably wind up talking about Grandpa bassoon and Auntie English Horn, that sort of baby talk. I can't bear to do that to you. You're too sophisticated for that.

So I'll just give it to you straight, and quickly and painlessly.

OK. There are four main sections in the orchestra; the strings, the woodwinds, the brass and the percussion. Simple? The strings are the main body of the orchestra, in quantity as well as in basic responsibility.

[STAND]

There are 67 of them standing here, which is quite a multitude when you think of it, ranging from the high violins here, to the low double basses over there. Ladies and gentlemen, be seated.

[SIT]

Usually the highest string parts are assigned to the first violins, like the sopranos of a chorus:

[THEY PLAY: High E FP & hold.]

And the next highest parts go to the 2nd violins, who are like the altos of a chorus:

[THEY PLAY: C# - 6th below FP & hold.]

And the middle voices usually go to the violas, which are somewhat larger and lower-sounding, than violins and could be said to be the tenors of this orchestral chorus.

[THEY PLAY: Middle B, FP & hold]

Now the cellos here, or celli in Italian, are like the baritones of a chorus.

[THEY PLAY: Play Low E, FP & hold]

and the basses are, of course, the basses.

[THEY PLAY: Play Open E & hold]

[LB cut off entire strg. chord]

NOW the tricky thing is that the violins can also play low as well as high:

[NADIN EX: low G-string open — (hold over thru cello)]

and the cellos can also play high as well as low:

[EX: G - 2 octaves above violins. (Cut off together.)]

So you see the strings are a very flexible and useful section of the orchestra. They are also capable of playing very loudly:

[EX: Chord ad lib and very softly.]

_ They are also capable of hammering notes out.

[EX: Repeated down-bows]

or of plucking sounds which are called in the trade pizzicato —

[EX. Repeated pizz.]

And there are all kinds of other weird and wonderful sounds they can make which we won't go into because we haven't time. Oh, and let's not forget the piano and the harp, which don't look like stringed instruments, but are, because — well because they have strings, so they're stringed instruments.

All right. on to the woodwinds — a smaller but equally important and flexible department of the orchestra.

[STAND]

This is a totally different set of sounds, and very different from one another too. In fact, some woodwinds aren't even made of wood.

[SIT]

For instance, the flute, which is made of silver

[SHOW]

[STAND AND ALL SIT BUT BAKER]

and is held laterally.

[EX: Baker — one note]

Now this is the soprano of the woodwind section, with a range going from her low C to an octave above her high C, and octave ABOVE high C — which is more than any soprano I know can do.

[EX: FLUTE Low C - Hi C]

Now comes the oboe, which is made of wood, and held frontward and played through a mouthpiece of carefully cut reed - two reeds, actually, stuck together, leaving a tiny air-space for the breath to penetrate. It's one of the hardest instruments to play.

[EX: One note]

Now this oboe is also a soprano, as you can hear, with a wide range starting with her (or his) low C. and soaring up above high C -

[EX.]

Great - I'm sure you all know a clarinet when you meet one. He's also made of wood, but with a single reed mouthpiece, and he's even rangier than the oboe -he can go lower and higher, and faster and funnier -

[EX.]

And finally the bass of the woodwind section, the bassoon, again made of wood with a double-reed mouthpiece like the oboe, but much longer and gloomier.

[EX: Low range]

Now those are the four basic instruments of the woodwind section - flute, oboe, clarinet and bassoon. But you should know that there are also smaller and larger versions of each one - for instance there's a small, higher flute called the piccolo.

[STAND AND PLAY AND SIT]

There is a larger, lower oboe, called confusingly enough, the English Horn.

[STAND AND PLAY 1 NOTE AND SIT]

There's a larger, lower clarinet, called the bass clarinet.

[STAND AND PLAY AND SIT]

and there's a much larger, much lower bassoon, called the double bassoon.

[STAND AND PLAY AND SIT]

And there are many variations too. And all these wind instruments can also play loudly or softly, rhythmically or songfully, together as a choir, or alone as soloists.

And what soloists they are: they are the most often called upon to be the solo stars of the orchestra.

And now here are the big, beautiful brass.

[STAND]

This is the big sound of the orchestra almost always called in at the climaxes.

[EX: Ad lib chord]

[REMAIN STANDING]

Terrific. But they are also capable of mellow songfulness and of quiet chorale playing, and of gentle solo playing. Again, there are high ones and low ones. The highs are the trumpets:

[EX. (PLAY AND SIT)]

and the lows, or course, are the trombones:

[EX. (PLAY AND SIT)]

And of course, the lowest of all, the bass tuba:

[EX. (PLAY AND SIT)]

Now between these two extremes of high and low, are the French Horns which are a special case. You see, they're made of brass, all right. but they're often considered to be part of the woodwind section rather than the brass section, because they blend so well with the woodwinds. They're like certain people we all know who try to be on both sides of a fence at the same time; put them with the winds and they sound like winds; put them with the brass, and they sound like brass. But left to themselves, they sound exactly like French Horns, and there's no mistaking them.

[EX: All horns (Unison) Till theme]

[SIT]

Terrific - what a range they have - from all the way [sing] to [sing] And finally there is what is sometimes called the kitchen of the orchestra - the percussion section. This is usually thought of as the noise department - but these instruments can also play delicately, beautifully, and with great artistry. They are headed by the timpani or kettledrums.

[EX.]

and they include a whole raft of noise-makers- I don't mean only that they're loud, but that they make noises rather than specific notes. In other words, they are instruments without pitch - you can't play a tune on them. For instance - the triangle,

[EX.]

the snare drum,

[EX.]

the tenor drum,

[EX.]

the bass drum,

[EX.]

the wood-blocks,

[EX.]

the temple blocks,

[EX.]

the cymbals,

[EX.]

the gongs

[EX.]

And a whole variety of, objects which are scraped, rubbed, cranked, slapped rattled, clicked and otherwise maltreated.

But let's not forget that there are some percussion instruments which are pitched,(like the tympani) and which can play tunes very well. For instance the xylophone,

[EX.]

and the glockenspiel,

[EX.]

and the chimes,

[EX.]

and lots of others. Well, there you have it, the bare bones of the orchestra. And for the next half hour we're going to see, by dissection and X-ray, just how all these wildly different instruments of wood, silver, brass, cat-gut, horse-hair, calf-skin, copper steel and nylon all manage to produce the glorious sound of Respighi's wide-screen, glowing technicolor, epic spectacular, "The Pines of Rome".

Respighi's "Pines of Rome" is or are divided into four continuous movements, each one named for certain aspects, or areas, of the city of Rome. The first movement is called The Pines of the Villa Borghese — the Villa Borghese being a famous park in the middle of Rome, a park famous, among other things, for the hordes of children who always seem to be playing there. And so this opening movement is a romp, full of the squealing of high-pitched young, voices, of yelling and teasing, and of the kids' tunes that go with games, especially soldier-games. Here's how it begins :

[EX: Opg. to Reh. No 1 thru the bar]

Now let's put our X-ray eye on that dizzying sound, and see just what makes it. First of all, there's that squealing made by trills in the strings and the oboes:

[EX: Squeals, trills]

OK, got that. Now there's the suggestion of rushing around, made by racing figurations in the flutes, clarinets, the piano and harp and the pitched percussion instruments:

[EX]

And on top of all that there's a mad tintinabulation on the triangle:

[EX: triangle]

Imagine one little triangle making all that noise! And finally there are the trumpet fanfares, telling us that we're playing soldiers.

[EX: trumpets]

Now you put that all together, and you have this brilliant opening of The Pines of Rome.

[EX: (REPEAT) Op. Reh. l]

Terrific sound. Really original. Now against this shrill background erupts a lusty folk-tune or rather a game-tune - sort of the Italian equivalent of The Farmer In The Dell - which is played by a very special combo of instruments from different sections of the orchestra. Mainly the cellos, the English Horn and the Bassoon playing way up high, it's a low instrument playing high, and a French Horn playing the main notes of the tune, only not the whole thing, but accenting them.

This method of combining unrelated instruments together is called doubling, which means simply what it says: coupling different instruments on the same tune.

Here's what it sounds like with all the combo together.

[EX: 2nd bar 1 to dbt. 10th bar]

And now listen to that tune against its background of the squealing and yelling, and you'll get a real picture of the symphony orchestra in action — as well as a sound-picture of kids playing in the Villa Borghese.

[EX: Opg: to dbt. of bar 19]

Marvelous sound, isn't it? So vivid and bright. Well now all this dissection we've been doing up to now has taken care of exactly thirteen seconds of music; so you can see that if we went on X-raying every bar of the piece at this rate we'd finish our anatomy lesson next Purim. So we're going to have to skip.

All right; we skip to another spot in this first movement, again featuring trumpets being soldierly. They're still playing soldier games only this time accompanied by a Bronx cheer percussion instrument called the ratchet:

[EX: Ratchet]

You see, the game's getting rough. In fact, the fanfares are rudely interrupted at this point by violent jabs, as if the kids in the park are taking pokes at each other.

[EX: Tutti Reh. 5 for 8 bars]

Now those jabs are made mainly by the strings —

[EX: 5th bar of No. 5 for 4 bars Strings alone]

And notice again that the cellos are playing higher than the violins. This is a favorite trick of Respighi, putting low instruments into an unnaturally high register, you see. The violins are playing this:

[EX: Same as above, violins alone]

whereas the cellos are playing way up here:

[EX: Same as above, cellos alone]

You see, it makes the whole thing sound even jabbier, because the cellos playing way up in their high register can sound so nasty

[EX: CELLO]

Furthermore, these string-jabs are doubled by woodwind jabs.

[EX: Woodwind, 5th bar of No. 5, for 4 bars]

Of course, that nastiness comes partly from the dissonance of the notes (SING), but that dissonance is made even nastier by reinforcement from the french horns:

[EX: 6th bar of 5 for 3 bars]

Now that specially nasty effect you've just heard is due to the fact that these horns are playing muted, that is, with mutes stuck into them; (SHOW) Can we see those Mutes? Now mutes, as the name implies, are usually used to make an instrument sound softer and more distant; but if you do the opposite, if you mute a horn and then blow into it with all your might, you get a real nasty noise. Just compare: here are the horns without mutes, open:

[EX: 6th bar of No. 5 (minus mutes)]

And now they put in their mutes. They're closed and they sound like this:

[EX: Same with mutes]

You see? The very summit of nastiness. So now let's hear the whole thing again. The fanfares, and the jabs together.

[EX: No. 5 for 14 bars to dbt. of 15th bar]

X-ray completed. Well, that should be enough with the kiddies in the park, don't you think? On now to the second movement, which is called "Pines Near a Catacomb". You all know what's a catacomb? Well, it's an underground cemetery, and Rome is full of them, mostly housing the remains of countless Christian martyrs of early Roman times. So naturally, this music is going to be a sudden and immense contrast to the noisy gaiety of the first movement - this one is all mystery and twilight solemnity.

And in it, Respighi uses the orchestra in a most imaginative way to depict the evening shadows - a deep tolling church bell, and constant religious chanting going on and one of his most effective devices is a backstage trumpet solo suggesting, as if from far off, a hymn sung by the pure, high voices of young boys; and the spooky atmosphere surrounding this is meanwhile sustained by high muted strings. It sounds like this:

[EX: Strings & Off-stage trumpet Piu mosso, 4 bars w. fade]

Beautiful effect and now another chanting is heard, lower, faster, like the Gregorian chant you sometimes hear in Roman churches. And this is done by low, unmuted strings doubled by low clarinets and horns:

[EX: Ancora piu mosso. 1 bar only. Vc, Cb, Horns, Clarinets]

From here on, Respighi uses this insistent, haunting figure, to build up a big crescendo, finally arriving at an enormous climax, on which we'll now focus our x-ray machine. Look, the fast chant we just heard - this figure is now in the high strings, along with the winds and horns.

[EX: 4th bar of 11 for 1 bar only.]

And against this is sounded the boy's hymn we heard earlier in the off-stage trumpet, only now it's blared out by 3 trombones in unison.

[EX: 3 trombones in unison]

And under all this going together, marches a bell-like bass line - played by the cellos and basses, and the double-bassoon.

[EX: 4th bar of ll for 2 bars -bass, celli]

This heavy bass-line is made even more ponderous by the addition of the piano.

[EX: Piano bass line - 1 bar]

and especially by a really unusual instrument which is the great organ, here, of course, using only the pedals with his feet, to produce those low booming tones.

[EX: 1 bar - organ bass line]

Now, let's put all that back together and listen to this tremendous climax of the movement.

[EX: Tutti 4th after Reh(ll)for 4 bars w. fade]

What a sound. Well, gradually it diminishes, and as it finally dies away into silence we are led without pause into the third movement which is called The Pines of the Janiculum. The Janiculum is that great and beautiful Roman hill, one of the famous Seven Hills on which Rome was built.

This is now a pure atmosphere piece, suggesting the pines standing in bright moonlight like weird surrealistic sculptures. The atmosphere is set immediately at the beginning of the movement by a piano cadenza - you know what a cadenza is? A cadenza is a free improvisation - a pearly, romantic cadenza over a texture of muted strings.

[EX: Bar No. 2, piano & 2 bars]

That sets the moonlight mood, and now comes the moment for one of our stars of the woodwind section - the solo clarinet — to pour out a stream of melody like some mythical night-bird singing his heart out to the moon.

[EX: Upbeat to 13 for 3 bars]

Gorgeous, isn't it? Now this magical atmosphere builds up and fades away, ending with a repeat of the opening piano cadenza and, the clarinet melody of that mysterious night-bird. Only this time - are you ready for this? - as the clarinet fades away its last note is taken over by perhaps the most unusual instrument ever to be used in a symphony orchestra - a phonograph. Actually, a phonograph record of a real nightingale really singing in real Rome.

[EX: Gramophone until cue off]

Sounds insane; twittering away all by itself, but it's an unforgettable moment in the music when the nightingale is introduced with all the violins trilling away behind it. I'm not going to give that moment now; it's too special. When we play the whole piece in a few minutes you'll see what I mean.

At any rate, as the phonographic nightingale fades out, we are suddenly aware of the sound of distant marching feet, measured and relentless, and we are into the fourth and final movement, which is the most famous of all, called the Pine of the Appian Way.

(I'm sure you all know about the Appian Way - the Via Appia, that historic Roman road over which passed so many Roman armies, which has seen so many victors and victims, so much glory and cruelty.) Here are those fateful footsteps created by low strings, plus the timpani and the piano.

[EX: Low strings, tympani, piano 2 bars]

Now these instruments, once they've begun, never stop their ominous tread right up to the end of the piece; it is the build-up of all time, something like Ravel's "Bolero," as more and more sound is added as the armies swell to gigantic hordes, and the sun comes up in all its glory. Sounds corny - but it is corny. I told you it was a colossal spectacular but it's still almost impossible to resist the magic of this incredible march as it builds.

Now over these distant marching feet, the first sounds we hear are of lamentation - of captured slaves, of Christian martyrs, of massacred children, of all those horrors on which the glory that was Rome was built. Here's one lament; a real heart stab in the muted violins:

[EX: (Violin 2) 18 1 bar]

And here are more victims from the East, with an Oriental lament on the English Horn. I don't know why, but all Oriental laments seem to be on the English Horn.

[EX: (4 bars before 19) 2 bars]

But now the victims give way to the victors and we begin to get fanfares, military calls and tattoos, starting in low horns and bassoon.

[EX: fig 20, 2 bars + dbt.]

And suddenly, from another direction, from another army, comes another fanfare, played by offstage brass instruments.

[EX: 5 after (20) 2 bars + dbt.]

And these fanfares, sounding from every direction, are gradually taken up by all the wind and brass instruments, and as the footsteps grow nearer and heavier so do the fanfares; and more and more instruments join the procession, more drums, more cymbals, gongs, trumpets and finally the king of instruments, the organ full blast, this time, hands and feet. The effect is tremendous, but rather than show it to you now and give it away, let's save it for its rightful climactic place at the end of the complete performance of Pines of Rome, which is now forthcoming.

I only want to remind you that we start in the park of the Villa Borghese with the squawling children, then abruptly into the shadow of the Catacombs, then we are gently led up to the moonlit Janiculum, and finally into that mystic vision of

The armies marching on the Appian Way. You may have noticed, if you've been listening carefully, that the four movements that are played with pause, have a continuous time sequence; it is presumably late afternoon for the kids in the Villa Borghese - after school, naturally, and it has become twilight - vespers time - by the time we get to the Catacombs. Now it's deep night on the moonlit Janiculum, and it's dawn on the Appian Way, ending in a glorious sunrise. You may also have learned a little bit more about the anatomy of a symphony orchestra than you knew before.

So now as you listen, I hope you'll be hearing this orchestral sound in a new way, with a new intelligence and with x-ray ears.

I. THE PINES OF THE VILLA BORGHESE

II. PINES NEAR A CATACOMB

III. THE PINES OF THE JANICULUM

IV. THE PINES OF THE APPIAN WAY

END

© 1970, Amberson Holdings LLC.

All rights reserved.

Watch a video excerpt of "The Anatomy of a Symphony Orchestra"