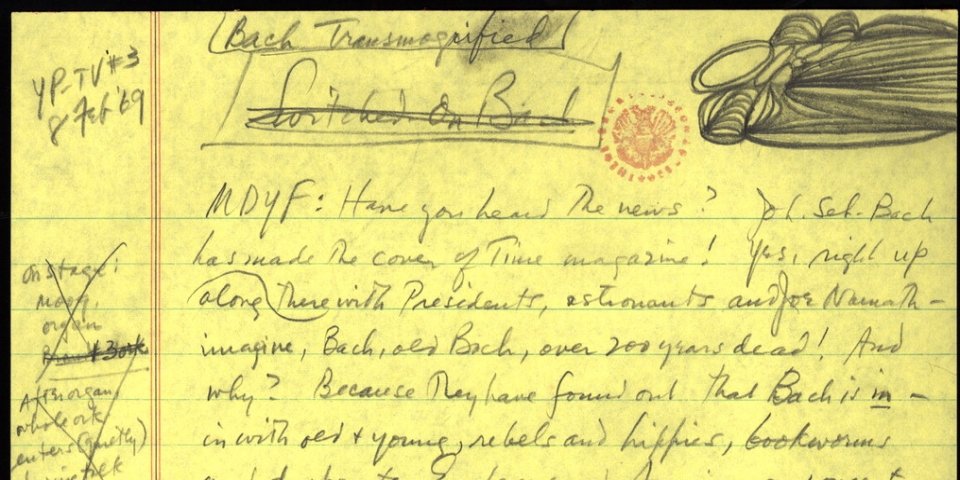

Lectures/Scripts/WritingsTelevision ScriptsYoung People's ConcertsBach Transmogrified

Young People's Concert

Bach Transmogrified

Written by Leonard Bernstein

Original CBS Television Network Broadcast Date: 27 April 1969

LEONARD BERNSTEIN:

My dear young friend:

Have you heard the news? Johann Sebastian Bach has made the cover of a national news magazine! I'm not saying which one, but he's right up there along with Presidents, astronauts and Joe Namath—imagine, Bach, old Bach, over 200 years dead! And why? Because they have suddenly found out that Bach is in—in with old and young, rebels and hippies, scholars and dropouts. Everyone who like music suddenly likes Bach. But actually there's nothing so new about it; Bach is always being discovered and dropped and rediscovered. It's an old story. He was even dropped by his own sons; they were the first to drop him, who thought of him as an old square. In fact, they used to call him the Old Wig behind his back. And then he was discovered a few years later.

But this latest rediscovery off Bach is supported by a host of new gimmicks and treatments and tricks that can be played on him. Bach's music just naturally seems to lend itself to treatments or trans-mogrifications, whether it's by the Swingle Singers, or Rock and Roll groups, or by way-out composers, or very serious conductors. And this is what our program is about today: Bach switched on, turned on, rocked, rolled, shaken and baked. What you're going to hear may astonish some of you, and outrage others—but it can't fail to fascinate you. And the most fascinating thing of all is likely to be the incredible spiritual vitality of the original, the Old Man's wiggy music—these magic notes that will last forever.

So let's start by hearing an original, famous Bach fugue—the so called "little" G-minor fugue for organ. We're going to hear it in three different ways: first in its pure form for the organ, and then in two transmogrifications—one a version for symphony orchestra, and the other a rather more kooky version for the newly famous Moog synthesizer. But more about that later: let's first listen to the fugue itself, as Bach conceived it, played by a marvelous young organist that we discovered at one of our auditions, the 21 year old Michael Korn.

[KORN: BACH—FUGUE IN G MINOR]

Bravo, Michael. Now that's a fugue you can hear once and never forget. But you're going to hear it three times, so you can be sure you'll never forget it. Now, about this second version for symphony orchestra: Orchestral transcriptions of Bach's organ and harpsichord music are usually made by conductors who are not satisfied with the small number of pieces Bach wrote for orchestra, to say nothing of the smallness of the orchestras he wrote them for. Now here are these virtuoso conductors with hundred-piece symphony orchestras, and no Bach for them to play.

So, these conductors reasoned, let's give them some Bach to play by making big, lavish transcriptions—and these are usually justified by the reasoning that if Bach were alive today, with these great, overwhelming orchestra-machines at his disposal, he would most certainly have given his music the same full treatment. I'm not completely sold on that argument, but many other conductors are, most notably the great and beloved Maestro Stokowski. He has made many Bach transcriptions over the years and one of the most famous is of this very G-minor fugue we just heard, and so here it is again, in the grand Stokowski manner. Of course, ideally, a Stokowski transcription should be conducted by Stokowski himself, and guess what: we have been lucky enough to persuade the great Maestro to come and conduct it for us in person.

How's that for an exciting bonus? We are proud to welcome none other than Leopold Stokowski.

[ORCH: Bach—Fugue in G Minor (Stokowski)]

Thank you Maestro.

And what a glorious sound that was.

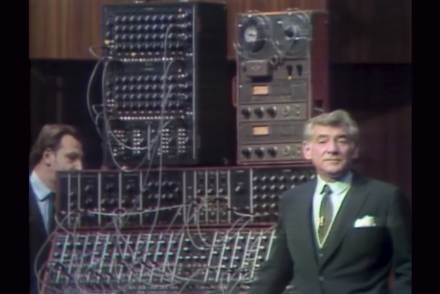

But of course, if you happen to be on the side of the purists and you think that's a distortion of the true Bach, wait 'till you hear the next one—which is a transmogrification of the same fugue again, but on the much written and talked about Moog Synthesizer. And here it comes now.

Hello Hal!

[ENTER MOOG]

How about that?

What you're going to hear now is that same Bach Fugue pre-recorded on a tape which was made by this incredible electronic instrument. It can do anything but stand up and take a bow; it can produce almost any kind of variation on pure sound including some sounds never heard before on this earth, at least:

and these sounds can then be dubbed onto tape in any combination from interplanetary noises to a Bach Fugue. But there's been so much talk and publicity about this extraordinary machine that I needn't take time to describe it in any further detail. Anyway, what do I know about oscillators and patch-panels and all that jazz? The thing about it that really interests us today is that this is the instrument on which has been recorded a very popular album called Switched-On Bach which I'm sure many of you here have listened to. Through this record-album, the Moog-Machine has made a startling contribution to the new Bach rage. The bizarre version of the Bach fugue it's about to play for us now was prepared by Walter Sear, who will operate the machine; now are you ready? Prepare decompression chambers. Force field operative. All systems go. And, blast off!

[MOOG: Bach—Little Fugue in g minor]

I think we've just about had that fugue, don't you?

So let's clear the air as soon as we clear the stage, by going to another famous Bach piece in a whole different key, this time it's for unaccompanied violin solo—that is, in Bach's original version. And after it you're going to hear a transmogrification of it that may make your hair stand on end. But first let's hear a little bit of the original—the Praeludeum, from Bach's E-major Partita played by our own distinguished concertmaster, David Nadien.

[Nadien: Bach—Partita in E Major]

I hate to stop that beautiful playing, but that's enough to give you sane idea of the piece, which goes on in much the same way for about four minutes. Now for the transmogrification: along comes one of our best-known and most talented composers, Lukas Foss, who for some years has been experimenting with various new wrinkles in the world of the so-called avant-garde, the way-out fringes of contemporary music.

Mr. Foss, who is also a fine conductor, has taken this we11-loved and world-famous piece of violin music, and has made—not a transcription at all, like in Stokowski's—but a whole new modern piece of his own, in which, astonishingly enough, every note comes from the Bach piece. But the way he puts these notes together is something else, as you'll hear in a moment.

Foss calls his piece Phorion—a Greek word meaning "stolen goods"—thereby emphasizing the fact that all the notes he uses are stolen—or borrowed—from Bach.

And he has subjected these notes to a highly unusual treatment, which I'll try to explain to you as briefly as I can.

First of all, each member of the orchestra has two sets of music in front of him: one a sheet containing Bach's original, and the other a complicated set of instructions. These instructions describe a series of musical events, the length of each event being more or less up to the whim of the conductor. Now also left to the conductor's whim are the entrances and exits of the various instrumental groups in the orchestra—with this one extra special added attraction that whenever a group of instruments is cued out by the conductor, they don't stop playing, but continue with their Bach notes, only inaudibly, without being heard. And that may sound impossible, but it's exactly so.

For instance, the cellos may be playing along, like this:

[EX:- CELLI]

when suddenly the conductor gives them the stop sign and they continue to finger the notes, but not to bow them, thus producing no sound except the tiny tapping of their fingers on the strings. Listen. Can you hear it? Meanwhile another group has been cued in, let's say the clarinets;

[EX:]

Then they are cued out and the cellos are cued back in, blooming suddenly into sound at whatever point they may have reached during their inaudible music: like this

[EX:]

You see it's a wild idea, but an exciting one, especially when the whole orchestra is doing it together, creating waves of sound rather like ocean waves rolling in unpredictably from any and all directions. But there's much more to this Phorion than that one trick: there are so-called supporting instruments, mostly brass and winds, that pick up occasional bits of the string music and join in, sometimes imitating them, sometimes mocking them. Now here's one example

EX: VIOLINS & SAX

And then there are three electric instruments—electric guitar, piano and organ who have their own separate instructions, which I won't go into—too complicated. And then there are different percussion groups stationed around the stage—with cymbals, gongs, anvils, and what-not—they support the instruments in front of them, and at other times join in battle with them, making random sounds of knocking, whipping, hammering or breaking. In fact, the first sound you'll hear, on the opening downbeat, includes the smashing of a soda bottle in a burlap bag.

And by the end of the piece, with everyone going at once for all they're worth, Bach has been turned into a bloody battlefield of noise. It's certainly not Bach any more, and you may not even think it winds up being music in its usual sense, but whatever it is, it's an intensely personal expression by a dedicated, talented composer who adores Bach, as I happen to know. So if he seems to you to be murdering Bach, it may be really that he is expressing something about our century that can be expressed only by committing this kind of violence on the music of the past.

This Phorion can amaze us and amuse us, even in the abbreviated version we're about to hear, but it can also tell us something awfully important if we listen with our minds as well as our ears. Here it goes.

[ORCH: FOSS - PHORION (EXCERPTS)]

So far, in our look at transmogrified Bach, we've spent much more time on the transmogrifications than on Bach himself—which is right, since that's what this program is about. But somewhere along the way we may begin to long for a bit more of the real thing—more than just a minute organ fugue and a snatch of a solo violin piece. So now, before our next and final transmogrification (which may turn out to be the wildest of all) let's hear a good solid hunk of untransmogrified Bach—namely the opening movement of the Fifth Brandenburg Concerto in D major, which is scored for a small string orchestra, as you see, with three soloists—violin, flute, and harpsichord.

Even this performance is going to be somewhat transmogrified—that is, not exactly as it was heard in Bach's day—since the string instruments are played very differently now from the way they were played then, plus the fact that the piano has replaced the harpsichord as the standard keyboard instrument. Besides we're going to shorten it a little bit. The solo parts will be played by David Nadien (who is certainly earning his bread today, by our great solo flautist Julius Baker, and yours truly at the keyboard. So let's give our undivided attention to the glories of Bach's concerto, before we let the N.Y. Rock and Roll Ensemble get their hot hands on it. David! Julie!

[ORCH: BRANDENBURG CONCERTO NO, 5 in D MAJOR 1st MOVEMENT]

Now at last we turn the stage over to those five mad geniuses who go by the name of the N.Y. Rock and Roll Ensemble. They are five hybrids—half blue-blood and half Beatle, half conservatory-trained and half trained in the college of hard rock.

I'm not quite sure what they're going to do with this music: we just presented them with the Fifth Brandenburg Concerto and said: take it from there. And wherever they take it, whether you approve or not, one thing is sure: it's going to be fun. And who knows: it may even be beautiful.

[NEW YORK ROCK AND ROLL ENSEMBLE: BRANDENBURG CONCERTO NO. 5 IN D MAJOR 1st MOVEMENT]

END

© 1969, Amberson Holdings LLC.

All rights reserved.