Lectures/Scripts/WritingsTelevision ScriptsYoung People's ConcertsBerlioz Takes a Trip

Young People's Concert

Berlioz Takes a Trip

Written by Leonard Bernstein

Original CBS Television Network Broadcast Date: 25 May 1969

Pretty spooky stuff. And it's spooky because those sounds you're hearing come from the first psychedelic symphony in history, the first musical description ever made of a trip, written one hundred thirty odd years before the Beatles, way back in 1830 by the brilliant French composer Hector Berlioz (That's Berlioz: the Z is pronounced). He called it Symphonie Fantastique, or "fantastic symphony," and fantastic it is, in every sense of the word, including psychedelic. And that's not just my own idea: It's a fact, because Berlioz himself tells us so. Just listen to these first two sentences of his own program note that he wrote describing the symphony. Quote:

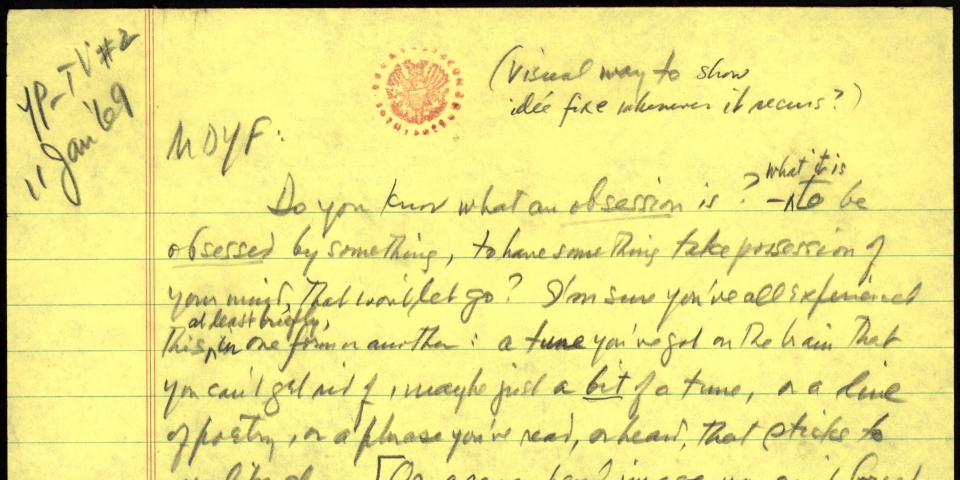

Unquote. Doesn't sound very different from modern days, does it? And we have every reason to suspect that the morbid young musician Berlioz is talking about is none other than Hector himself. He certainly did have fits of lovesick despair we're told, and he was a creature of wild imagination--wild enough to have these visions and fantasies without taking a dose of anything. His opium was simply his genius, which could transform these grotesque fantasies into music. Now listen to the next sentence of that same program-note: Quote: "Even the beloved one, herself, [the one who's made him lovesick] has become for him a melody, like a fixed idea which he hears everywhere, always returning." Unquote. A fixed idea--remember that, in French -- idée fixe, in other words, an obsession. You all know what an obsession is, it's something that takes hold of your mind and won't let go. Well, in this symphony the obsession is Berlioz's beloved, she who has made him so desperately lovesick. She haunts the symphony; wherever the music goes, she keeps intruding and interrupting, returning in endless forms and shapes.

So you can see that if we're going to understand anything about this weird symphony, the first thing we have to know is that idée fixe melody, the theme of the beloved, and be able to recognize it each time it appears, no matter how it's disguised. Here it is, or at least the first phrase of it:

That's the first phrase. Can you hear the lovesick yearning in that melody? The way it has a rising shape at the beginning

and then rising even higher, straining still further

and then even further

and then hopelessly collapsing

Isn't that a perfect musical picture of lovesick longing?

Now listen to it again, this time letting it continue into its second phrase, then its third, fourth, and so on, each time rising and straining further and further, and each time again falling back into despair.

Now I'm sure that any of you who has ever had a crush on someone who didn't return your feeling will understand that passionate melody perfectly; and you can easily see how a lovesick musician could become obsessed by it. And if you understand that, you're ready to hear the symphony.

Now the first movement is subtitled "Visions and Passions." And it all begins with a slow dreamlike introduction, which we're going to skip, since it only prepares the atmosphere for the entrance of that main theme--in other words, it paints for us the dreamy, romantic lover before the obsession hits him. But when it does hit--oh boy, just listen. Here's the end of the introduction as it leads into the first feverish outburst of the idée fixe theme--and listen for those psychedelic fireworks.

Did you get what I meant by "psychedelic fireworks"? Those sudden flashes and changes of color and the dazzling unexpectedness of those dynamic changes--you know what dynamic changes are, that is, changes from loud to soft and back again. There are dozens of them. And then when the theme did come in, did you hear how those rising and surging phrases are each written with its own little burst of crescendo?

And did you notice how Berlioz accompanies his melody? Very strangely indeed: with no accompaniment at all under the melody, but between the phrases those jerky little figures in the strings.

And they're so uneven--they are always popping in where you don't expect them.

And then the way the tempo is always changing, charging breathlessly ahead, and then slowly up, and then suddenly in time again, and suddenly slowing up again--you never know what's coming. I tell you, you can become a nervous wreck playing this symphony; but then, that's what it is: a portrait of a nervous wreck.

Well, by now you ought to have that theme down pat, so that you can follow it in all its psychedelic disguises and developments, through anxiety, jealousy, rage, despair, whatever. The rest of this first movement is almost all such developments of the theme--of course, we can't play you all of them, but let's have a couple, just to see how they work. Now here's one, where the low strings take up the theme, in a growling, menacing way, while over them the woodwinds and horns are heaving a series of heartbreaking sighs. This is a perfect picture of the agony of jealous rage.

Did you hear how that worked up into a climax of anguish? But if you think that was anguished, listen to how it goes on, with the sighs growing into howls and the strings rising to hysterical shrieks.

Now that time he almost flipped his lid. This music sometimes comes dangerously close to the borderline of insanity; every once in a while you think it may just go over the line--but it never does, because Berlioz is always in control, no matter how insane he seems to get.

Now just one more passage in this first movement--and the weirdest of all. This time the low strings are again moaning away on the idée fixe tune, only now in canon (you all know what a canon is, I won't even explain that), with the violas imitating the cellos--they sound together like a bunch of lovesick cattle. Here first are the cellos by themselves moaning away.

You know that tune. And here are the violas imitating them:

Now here they are together, in canon:

But all that is only the groundwork. Over it and above it rises a melody in the oboe, having nothing to do at all with the main theme--in fact, having nothing to do with anything much except maybe modern music, music to be written over a century later. This long melodic line in the oboe is one of those musical monuments in history, unlike anything else of its time, so weird that you can almost not tell what key it's in, or indeed if it's in a key at all. It's a marvelous representation of a sick wandering mind, a desperate soul, but the mind that composed it was not sick: It was pure genius. Now listen to this mad oboe:

Wow! Can you believe that was written in 1830, only three years after the death of classical old Beethoven? It sounds more like 1930--as though it were by Hindemith or Shostakovich or somebody. And on and on that oboe goes, rising dizzily over the canon of those moaning strings here, soaring to a new climax of hallucination. And when it gets there, as you're about to hear, the whole orchestra joins in, including trumpets for the first time, with the idée fixe melody in full swing of triumph, as though Berlioz had at last conquered his mania--but alas no, the madness takes hold again, dynamic flashes and all, and suddenly everything falls apart. The music splinters, like a smashed window, and finally dies away out of sheer exhaustion. In the final bars we hear one last longing whisper of the idée fixe melody, and the movement ends with a few organ-like chords of religious comfort. Now here is that whole last section of the psychedelic first movement, starting with the mad oboe solo.

End of Scene I, and end of dream one. Now a new dream. New scenery: an elegant ballroom, at first shadowy, and gradually becoming lighter and brighter, until we are in the midst of a brilliant party. Two harps now join the orchestra which give a ringing shine to the music, the music, of course, being a waltz, a charming, whirling French waltz. But after a minute or so the tune changes mysteriously--to what? Guess. To the idée fixe naturally, and there indeed is the beloved's face appearing and vanishing among the dancers. The desperate lover reaches out for her, but she's never there; the more he reaches the more she eludes him. Finally the waltz hits its climax--and suddenly everything stops: Nothing is there but the tune, the obsession, and for a moment it seems possible that he will have her and hold her. But then the waltz-world crashes in on him, he is separated from her by all those thousands of waltzers, whirling faster and faster around him--and he wakes up. Another fantastic nightmare. Here is the entire second movement of Berlioz's masterpiece--the scene of the ball.

You know, one of the most fantastic things about this Fantastic Symphony is that Berlioz was only a lad of twenty-six when he wrote this incredible new music. And I mean new: Try to think how amazing this Fantastique must have sounded in 1830, even after the wildest late works of Beethoven. This youthful symphony must have seemed to come from a whole other planet--a new world called romanticism.

For instance, take this third movement coming up, a "Scene in the Countryside." Now Beethoven had already written his scene in the countryside--the famous Pastorale Symphony, which you all know, with its shepherd calls, and birdcalls, and murmuring brooks and raging storms. But they were nothing compared to this. For instance, Berlioz writes real thunder in his storm scenes, using four different timpani-players--that's something classical old Beethoven would never have thought of. And Berlioz's shepherds don't just play their pipes--they play out a whole drama.

Here's the idea of the drama. Our poor drugged lover is now dreaming his scene in the country; for a moment it's not a nightmare but a peaceful dream of nature's beauty and repose. There's a shepherd playing to his flocks, who's answered by another shepherd way off on a distant slope. This duet of the shepherds is somehow comforting to our hero's loneliness: There is human communication in the world, even if people are far away from each other. Now let's listen just for a moment to those two shepherds:

Now there's a romantic piece of tone-painting: you can almost see the alpine countryside scene. And in this atmosphere Berlioz's hero dreams peacefully for a long while; the birds call sweetly, there seems to be hope (we're going to skip all that part, it's just too hopeful)--but suddenly the atmosphere changes, the skies darken, agitation seizes the music, and Guess-Who appears, taunting him with her idée fixe melody, a wolf-girl in sheep's clothing. Now here is that moment of truth:

What a nightmare. What a marvelous picture of panic and terror, with that breathless panting as it gradually subsides. Well now again there is some kind of peace and quiet, which we'll skip; our dreamer seems to be saved again from his obsession; but Berlioz has another horror up his sleeve--the final page of the movement. In this one extraordinary page he gives us a dramatic picture of the pain of loneliness that has probably never been equaled, not even by the most neurotic composers of our own century. And what happens is this: That shepherd begins his tune again--one phrase. We wait for the answer from his distant friend, but there is no answer. Instead, only a mysterious rumble of thunder. The shepherd tries again, another phrase; again the hollow answer of thunder. And so little by little the scene dies: The shepherd gives up completely, the thunder fades away completely, and our dreamer is left alone with the terrifying silence of lovelessness.

Scene four, or fourth movement. Change of scene: a new nightmare. In this dream our lover, our hero is a murderer--and whom has he murdered? Guess. His beloved, naturally, and the scene is the place of execution; he must now pay for his crime at the guillotine. This whole movement is a gruesome march, complete with the drums and brass of the execution squad. It's a great march, brilliant and horrible at the same time. At the end of it, our agonized dreamer arrives at the stake, bows his head to the blade--the music is by now savage, out of its mind--when suddenly, as happens in dreams, everything stops, and for one instant he sees, or hears, his beloved, the idée fixe, that melody. But only for an instant. The familiar phrase hangs there in the air on the clarinet, and--bang, it's cut off along with our hero's head. There's a roll of drums, a blare of brass, end of nightmare. And here is the fourth movement, "The March to the Scaffold."

Wait, wait, it's not over yet! There's a fifth and final dream that even tops that one--the nightmare of "The Witches' Sabbath," which is the topper of the whole trip. The lover now is dreaming he is dead; he is at his own funeral. But this is no solemn funeral; there are no holy words, and no prayers. There are only the grisly shrieks of witches,

and there's the blood-curdling laughter of demons and devils,

and the diabolical dancing of Halloween hags and grinning monsters.

And, of course, who should be the chief witch: None other than that sweet little beloved of his, whose angelic melody is now transformed into a hellish, squealing ride on a broomstick.

And then there are spine-chilling funeral bells,

and there's a parody of the Dies Irae chant from the Mass for the Dead:

and there's the writhing of evil snakes:

and the rattling of skeleton bones:

And much much more--but I want to leave a little something for your own imagination.

Now all this horror builds up into a most brilliant ending--but brilliant or not, I'm sorry to say, it leaves our hero still in the clutches of his opium nightmare. It's brilliance without glory--that's the problem. I can't honestly tell you that we have gone through the fires of hell with our hero and come out nobler and wiser, but that's the way with trips, and Berlioz tells it like it is. Now there was an honest man. You take a trip, you wind up screaming at your own funeral.

END

© 1969, Amberson Holdings LLC.

All rights reserved.