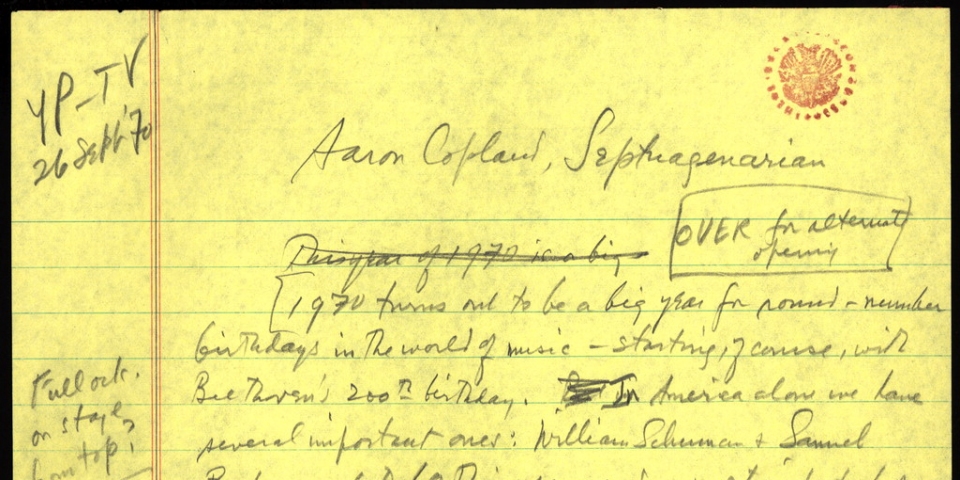

Lectures/Scripts/WritingsTelevision ScriptsYoung People's ConcertsA Copland Celebration

Young People's Concert

A Copland Celebration

Written by Leonard Bernstein

Original CBS Television Network Broadcast Date: 27 December 1970

LEONARD BERNSTEIN:

My dear young friends:

It seems only a couple of years ago that we had a Young People's program back in Carnegie Hall honoring the great American composer Aaron Copland's 60th birthday. I remember it as if it were yesterday - I don't know if you do, but I do - and it's almost impossible to believe that the time has rushed by so fast that this year Copland is suddenly 70, as of November 14th.

Copland has often been called the "Dean of American Composers" - whatever that means. I suppose it means that he's the oldest, but he isn't the oldest, he's just unique. He has led American music through paths both pleasant and thorny for half a century, and he has never ceased fighting for the cause of new music, especially new American music. What's more, he has been the idol and teacher and model for more young composers than you can count, and through his music and his books he has entered minds and hearts of millions of music lovers. In short, he is a National Treasure; and if we had a Legion of Honor in this country, Aaron Copland should be a Commander.

But we're going to honor him today by playing two of his most popular works, his Clarinet Concerto, and a suite from his famous ballet Billy The Kid.

Both of these pieces are on rather the light side — at least compared to his symphonies and his chamber music - but they're not so light that they don't show almost every important aspect of his style. And by style I don't mean anything as superficial as fashion in clothes or quick fads. Copland's style is his musical speech itself, a very personal language which we might call Coplandese, through which he speaks directly, clearly, gracefully and forcefully to all his hearers.

Take, for instance, the Clarinet Concerto, which we're going to hear first.

It's a rather short piece in one continuous movement, the first half slow and the second half fast, with the two halves separated by a brilliant cadenza for the clarinet alone.

Now in this fast second part we get a clear, bright picture of one aspect of Coplandese, which is the big-city sophisticated, Copland style, which is nourished on jazz, on New York slang, Latin-American rhythms, the tough accents of the city streets. Like this tune:

You see what I mean. But it's not just raw jazz: there's always a personal style of Copland that gives it a certain elegance, a humor of his own, like this:

You'll also hear another typical Copland element which is those biting, funky dissonances that 20 years ago, when the piece was written, used to make people wince at what they called "crazy modern music" but which today seem as right and simple as an average Rock group.

That last dissonance was mine, not his.

Don't forget that this Clarinet Concerto was commissioned and first performed by Benny Goodman, the King of Swing; and these days, when we're all rediscovering the swing era,and big bands, and jazz and the rest, this concerto seems more timely than ever before. And one of the miracles of the piece is that all this jazzy music is scored for an orchestra with no brass, and no percussion at all - imagine, jazz without drums! - and yet it all comes swinging out with a great beat, out of a simple orchestra made up of only strings, a harp, a piano, and naturally the solo clarinet. Of course, this piece isn't all swinging jazz: remember, there's that slow section at the beginning I talked about, and a beauty it is - which shows us another aspect of the Copland language - the simple, singing, lyrical side. It's simple - but so special, so sophisticated, every note chosen with immense care; so that no matter how simple the music is it is always as fresh as new bread.

When Copland first wrote this Concerto back in 1948, and he played it for me on the piano, I became very conscious of this highly selective note picking. I remember his playing the ravishing opening theme (PLAY AND TALK OVER) and when he came to this note (GET TO NOTE) that one. That Eb in the bass, I involuntarily went "umh" with delight and Copland said: "That's the note that costs'." And that's just the whole point about Copland; his notes are expensive, not just lots of notes a dime a dozen. So let's now listen to this expensive Concerto and here to play it with us is our high-priced soloist, the Philharmonic's great solo clarinetist, Stanley Drucker.

Well, so far we've been listening to one kind of Coplandese - let's say one of his dialects - the big-city vernacular, born of jazz. Now we're going to hear a whole other dialect, just as much a part of the Coplandese language, only this time born in the wide open spaces of the American West. The accent is completely changed now, from urban to rural, from New York jive to New Mexico twang, mixed with a bit of cowboy drawl and hot Mexican pepper. And yet it all comes out Copland, immediately recognizable, so strong is the force of Copland's personality. It shines through everything he writes. I have always considered his ballet Billy the Kid a masterpiece of stage-music; it's not only rousing but also tender; and in its opening and closing pages it even has a majesty and grandeur as wide as the prairie, as lofty as the Rockies, like this:

See what I mean by lofty? That happens at the beginning and the end of the suite. But in between that opening and closing music we are told the story of Billy the Kid, who was one of America's great bandit heroes. Every country has its bandit-heroes - England has its Robin Hood, Germany has Til Eulenspiegel, and Russia has Stenka Razhin. But Billy the boy-bandit is held in particular affection by Americans - I guess because he was so young and attractive and such a smash with the girls. (He was only 30 or so when the sheriff finally got him.) Besides, unlike Robin Hood or Til Eulenspiegel, he was a real person of fairly recent history. Actually, he died less than a century ago. In the ballet the story is quickly told of Billy's short career: seeing his mother killed before his eyes when he was only twelve years old and promptly killing her killers in revenge; and from then on becoming the famous outlaw we know about - the legendary terror of the West. He is finally hunted down by a posse, ambushed at night in the desert, and that's it, pardner.

To tell this story in music, Copland has naturally made use of a number of well-known cowboy songs, but he never just quotes them, rather, he transforms them by some magic into his own music. That's why I call it a masterpiece; it's a model of how to use folk-music in a symphonic way without just making high-powered arrangements of the tunes. Let me show you what I mean. (CROSS TO PIANO) For instance, just after that majestic open prairie music, we get a sequence describing a street in a frontier town, with all its familiar furnishings of cowboys, Mexicans, saloons, brawls, horses - that whole well-known Hollywood scene. And in this one scene Copland uses at least half a dozen cowboy tunes - in his very own way. Here's one of them, in the original called "Git Along Little Dogies".

When I was out walking out one morning for pleasure,

I met a young boy a-riding along;

His hat was thrown back and his spurs was a-jingling,

As he approached he was singing this song:

Yippee yo ti ye, get along little doggies,

It's your misfortune and none of my own.

Yippee yo ti ye, get along little doggies,

You know Wyoming will be your new home.

That doesn't deserve a hand. However, wait 'till you hear what happens when Copland gets a hold of it in his ballet. Like this spot, where he completely changes the rhythm of that tune and throws in a couple of peppery little dissonances, and out comes this.

You see? He's even added a typical cowboy yodel at the end, YIPEE (SING) and then he takes that little yodel and turns it into a loping horseback rhythm (PLAY) which in turn becomes the accompaniment for the next tune which sounds like this:

Now, isn't that great? Now that new tune you just heard comes from an old pioneer ballad called Great Grand-Dad, which goes like this:

Great grand-dad when the land was young,

Barred the door with a wagon tong.

For the times was rough and the redskins mocked,

And he sayed his prayers with his shot-gun cocked.

That was a tongue-twister.

Anyway, now look at what else Copland does to that little old ditty:

Could you tell what happened this time? The tune itself remained practically as I sang it, in a straight 2-beat (SING:) but the accompaniment was, of all things, a waltz rhythm in 3. Listen:

...and that rhythm works directly against the rhythm of the tune, so that you get a real Copland case of cross-rhythms:

You see, and that's what makes the difference between a mere arrangement and really original music. Then he does the same trick of cross-rhythms, only using the first tune about the Little Doggies, in a sort of variation, and it comes out sounding like this:

You see what fun he has with that tune, and how original he makes it sound? But if you think that's far-out rhythm, listen to what he does with this tune, called "Trouble for the Range Cook;" you may not know it under that title:

Come wrangle your bronco and saddle him quick,

The cook is in trouble down there by the crick

I guess you all know that. Well, this naive little tune really gets rough treatment: Copland puts it into the cockeyed meter of 5/8 time, with a 4/8 thrown in here and there just to make it a little more cockeyed: and out comes this Mexican jarabe:

How's that for a transformation? - from a little innocent waltz into a real symphonic grabber. And there are lots more familiar cowboy tunes used in this way before this street scene ends. Like Goodbye, Old Paint, I'm Leavin' Cheyenne, The Chisholm Trail, and so on. I wish I had time to show them all to you, and show you what Copland does with them. But by the end of the scene, the 12-year old Billy has seen his mother shot, and the trouble has begun. Billy is pursued by the law for the rest of his life. It's one long running gun battle from then on.

And as the smoke clears away, we are left with the tantalizing question - did they get him or didn't they? And that's a Cliff-Hanger.

And now, at last, we're going to hear an abridged version of Copland's "Billy the Kid", starting with that majestic open-prairie music we heard before, followed by the frontier-town street music we went into in such detail, and then, skipping a lot of the story, the honky-tonk dance in which the posse that has captured Billy gets drunk and celebrates the capture, then a short, tender passage describing Billy's death, and finally the return of the introductory music that tells us of America's great open spaces. And to Aaron Copland from all of us here, our loving and respectful wishes for a happy birthday.

END

© 1970, Amberson Holdings LLC.

All rights reserved.