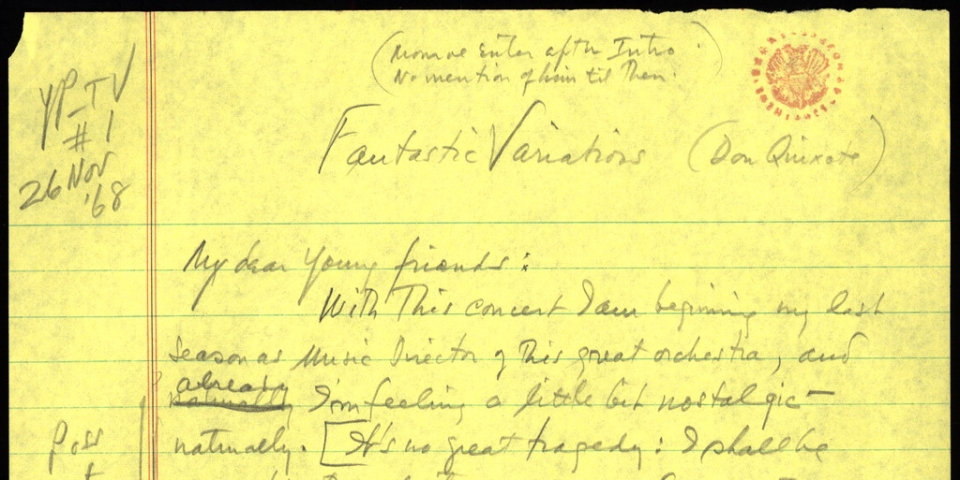

Lectures/Scripts/WritingsTelevision ScriptsYoung People's ConcertsFantastic Variations

Young People's Concert

Fantastic Variations

Written by Leonard Bernstein

Original CBS Television Network Broadcast Date: 25 December 1968

LEONARD BERNSTEIN:

My dear young friends: This is going to be my last Season as Music Director of the New York Philharmonic and naturally I'm already feeling a little bit nostalgic. I can't help looking back to the beginning of my relationship with this great orchestra, twenty-five years ago, heavens, when I was its assistant conductor, and made my debut unexpectedly, by replacing Bruno Writer who had caught the flu. On that program, the main event was the fabulous tone-poem Don Quixote by Richard Strauss, and I would like to indulge my nostalgic mood today by playing it again, and sharing it with you. Besides, it's a masterpiece, and you ought to know it anyway — it's one of the big ones, like the novel by Cervantes on which it is based — funny, wise, romantically warm, and philosophically cool. Very up-to-date, as you'll see,

That marvelous Spanish novel by Cervantes is, of course, one of the all-time classics, about three and-a-half centuries old; but as I say, very up to date. It concerns an aged gentleman named Don Quixote (or Don Quixote, as the British like to say, or Don Quichotte, as the French and Germans say) — anyway, Don Quixote, an aged gentleman of La Mancha (plug!) who in his declining years has become obsessed by the idea of chivalry - that is, gallant knights on horseback sort of thing, roaming the world searching out evil and finding causes to champion, especially the cause of purity, for example, find the pure, ideal woman. The old Don has been reading every word he can find on the subject — book after book — until his poor old head is so crammed with giants, ogres, enemies, infidels, evil magicians and the like that he is impelled to set forth on his skinny old nag Rosinante, suffocating in his heavy, rusty armor, and put all evil to the sword -— all, of course, in the name of his fair beloved, Dulcinea, whom, needless to say, he has completely made up.

In short, the whole long novel is a hilarious account of the poor old. Don's knightly exploits — that's knightly with a K — as he and his fat faithful little squire, whose name is Sancho Panza, roam about rooting out evil for the sake of the lovely Dulcinea. They have a long series of fantastic adventures, at the end of which Quixote finally realizes his folly and goes home to die peacefully in bed. I'm tempted to go into the philosophical meanings behind all this — there are many — it's all so relevant to us today with our peculiar 20th century brand of madness - but if I do we'll never get to the music.

Ah, the music! What makes Strauss' Don Quixote so remarkable is the way he has succeeded in catching the literary and pictorial elements of the novel in all their wit and variety. This tone poem is probably the most literary piece of music ever written, and in it Strauss gives us a detailed musical picture of this marvelous madman that is almost more vivid than Cervantes' original picture, because of the special power that music has to reach so deeply into us.

Now as someone said the other day, "That Quixote piece sure is a purty song." Now Strauss subtitles this pretty song Fantastic Variations on a Theme of Knightly Character. And what is this theme, so gallant and chivalrous? Well, it's hard to say, because it appears in so many different shapes and sizes even before the variations begin! In its most primitive shape and size it's basically these six notes, which never appear in this simple form until the end of the piece:

PLAY: A, B, F, D, F, ADoesn't sound too promising, does it? Or even very knightly in character. But let's see what glorious, gallant forms Strauss can give these few ordinary notes.

We hear it first at the very beginning of the piece in a very cavalier, off-hand way, right at the beginning, as the idea of becoming a knight-errant might first have flashed for a second across that fevered mind:

Now how's that for a magic change? Those same six ordinary notes, but we can already smell the idea, through the rhythmic suggestion of a knight-on-horseback.

Just listen to it again:

Glorious, isn't it? Now here's another startling metamorphosis: the same notes, but in the minor, proclaiming the old Don's urge to fare forth and fight:

And now, most magically, the same five notes extending themselves is almost like a tapeworm, as the idea of becoming a knight takes root and grows in Don Quixote's addled brain. This long, meandering line is almost like a documentary image of a wandering mind losing its marbles.

Now, you may have noticed that that was only the first five of the six notes - I don't know if you did, but it's true. But anyway, that's show business.

He's really flipping, isn't he? And all these versions of the same theme are surrounded by other themes and tunes and musical ideas representing various aspects of knighthood: like knightly courtesy:

very courteous.

And then there's knightly dignity:

— and then there's knightly passion;

very passionate

— and all this courtesy and dignity and passion for what? For Dulcinea, of course, the ideal, the unattainable, the impossibly flawless woman. And she goes like this:

Now all these themes — and more — get mixed up and shoved around in a staggering introduction that shows us Don Quixote's steadily mounting resolve to become a knight.

And this muddling together of the themes is a brilliant musical picture of the ideas that are whirring about in Don Quixote's muddled head; and it leads us to the climactic moment when, in a series of wild, dissonant chords, we hear the Don make his irreversble decision to set out on his adventures. Now here's the final stretch of that muddled introduction as it leads us to the climax.

And so the dear old mad man of La Mancha has acquired a new self-image: That of the young Knight-Errant of La Mancha, a man of vision and purpose, and, as Cervantes puts it, of a "Sorrowful Countenance" — that is, he's sorrowful at all the world's evil that must be destroyed, yet he's burning inside with an insane zeal to destroy it. And this image of himself, both loony and at the same time oddly touching, is given by Strauss to a solo 'cellist, who for the rest of the piece will represent, illustrate, and be Don Quixote. And here he is — the mad knight himself, in the person of our own Solo cellist of the N.Y. Philharmonic, Lorne Munroe.

And now Strauss, through his soloist, gives us a portrait of Don Quixote, the knight of the sorrowful countenance:

A perfect little portrait - sad, noble, gallant. And now a second portrait is shown us, that of Sancho Panza, the Don's loyal squire, servant, groom and companion, and his master's complete opposite: down-to-earth, practical, talkative, full of clichés, but with a certain peasant wisdom — in short, a perfect straight-man for the old Don, who is forever off on Cloud Nine. Now Sancho is portrayed by Strauss through three characteristic instruments: the tenor-tuba (STANDS) and the bass-clarinet (STANDS) both of whom represent the lumpish, oafish side of him, and by a solo viola (STANDS) which depicts the vocal, chattery sound of him. This part is played by our viola soloist, William Lincer. (ALL 3 SIT.) — And here is Sancho Panza.

Now that the main themes have been laid out for us, we are ready to follow the adventures of our characters. And these adventures are related to us by Strauss in the form of Variations on those themes — especially the theme of Don Quixote himself. For instance, in Variation I, the solo cello shows us the Don setting out on his limping excuse-for-a horse, while underneath the bass-clarinet shows us Sancho Panza close behind him on his donkey. And then over both of them floats the melody of Dulcinea, the guiding light. A very peculiar group they are, and yet a perfect musical combination. All three themes together, as they lumber along, the Knight and his squire suddenly come upon a group of windmills standing on a plain, their huge arms turning steadily against the sky.

Dear old Don Quixote is convinced that they are not windmills but evil giants, and in spite of Sancho Panza's protests, he charges full tilt into them, of course getting slapped down hard by those uncaring arms. All this is very clearly heard in the music; and my favorite moment comes just after the blow, as the arms of the windmill are heard, or seen, moving implacably on as though nothing had happened, while Don Quixote lies on the ground stunned and groaning. There's something very Charlie Chaplinesque about this — that combination of wild slapstick — comedy and sympathy for the little guy that makes you unsure whether to laugh or cry at it. Now here's that first famous Windmill Variation.

Poor man. But you see how gallantly he has recovered his dignity, picked himself up, and is ready for the next adventure. And this time his imagined enemies are not giants, but the entire massed armies of the fabulous Emperor Alifanfaron. Of course, as you will instantly hear, these armies are nothing but a large flock of sheep, as you will hear.

but to the eyes of our poor kooky hero, they are legions of infidels who must be vanquished. So again, it's Charge! and the sheep are routed, rushing off in all directions with the brass baa-ing wildly, and the victorious Don congratulating himself on his triumph. But, as you'll hear at the very end, Sancho Panza has his doubts about this victory.

Now here's Variation II: The encounter with the sheep.

That little doubting phrase expressed by Sancho begins a long discussion now between knight and squire, in which the pro's and con's of all this chivalry business are discussed. Sancho of course, holds out for the simple life, while the Don insists on ideals, dreams, goals, visions. This third variation is quite long; as we can't play all of it for you, but I do want to play you one section — one of the most beautiful and romantic moments in all of Strauss — the passage where Don Quixote defends his knighthood, and the principle of romantic idealism, the virtue of pure womanhood, and all the rest of it. This is the original model for every romantic Hollywood film score you've ever heard.

That is gorgeous, isn't it? And very convincing, except to Sancho Panza, who says:

.... meaning: H'm. At which the Don is enraged, and shouts:

.... meaning Shut up. And let's get on with our travels. Which they do, this time coming upon a procession of Pilgrims, new adventure, Pilgrims who are chanting as they plod along.

Again the daft Don sees them as a column of dangerous desperadoes; again he charges and is knocked senseless by these holy fellows who continue, on, chanting away, without having missed a note. Sancho Panza is torn between sympathy for his senseless master and the insane comedy of the scene, doesn't know whether to laugh or cry, but is finally overcome by the comedy and breaks into a, full-throated horse-laugh, as you'll hear, which is echoed by an equally mean bray from his donkey. Now here is Variation IV, the encounter with the pilgrims.

Poor Don Quixote — Poor man, bruised, battered, laughed at by his own squire. But he never loses his dignity — after all, the world of truth that he's seeking is far above Sancho's literal world of sheep and windmills. Quixote's truth is beyond hum-drum reality; it's poetic truth, that seeks justice for the weak, the pure and the noble against the so-called reality of the Establishment. And so the gentle Don draws himself up to his full height, and tells Sancho to go to sleep for the night while he, Quixote, will keep an all-night vigil over his armor, as great knights do. It's a glorious vigil he keeps, in this fourth Variation, as he meditates sadly on the ruthlessness and uselessness of so-called reality, and yearns under the stars for the non-existent Dulcinea. Then as the day breaks, this now being Variation V, Quixote's sleepless eyes behold a real-low-down country wench who is approaching him and this is told us musically in a brilliant transformation of the Dulcinea theme we've just been hearing into a coarse, sort of rock-and-roll version of the theme.

Don Quixote is convinced that this wench is Dulcinea transformed by a wicked magician into a common hussy. As you can see, nothing can phase our hero; he never loses his faith, his hope, or his dignity. So, Here are Variations V and VI ' together — first the real Dulcinea and then the false Dulcinea — or is it really the other way around?

You know, in a way it's a kind of desecration to talk your way through a piece of music, interrupting constantly to explain what's coming. But this piece is not like most music, in that it has a very specific story running through it, every second and every single bar, so you can't fully understand the music without the story; and besides, the piece is filled with many convenient pauses, as though Strauss had just put them there to help us out in our explanation.

At any rate, from here until the finale of the piece, all the remaining Variations are one long series of disasters, delusions and defeats. For instance, they get into what they think is an enchanted boat which turns out to be a leaky old rowboat without any oars, and of course they wind up very wet. And another time Don Quixote attacks two fat old monks on muleback whom he mistakes for evil sorcerers - same old story. But perhaps the most famous of these Variations; which we're now going, to hear, concerns a ride through the air, with the Don and his squire mounted, blindfolded, and mounted on what they believe to be the magic horse Pegasus, who is supposed to be able to fly them through space. In their boggled imagination this does indeed happen, very graphically, with the aid of a Wind-machine

plus a lot of other windy noises; but the low instrument of the orchestra never get off their one low note, which is D:

They're there throughout, thus informing us that Pegasus has remained earthbound throughout the flight. And here they go.

As you've just heard, there they were all the time, right down on the ground. But now comes Don Quixote's greatest disaster and final defeat: when he is challenged to a duel by a rival knight, who is known as the Knight of the White Moon; and the conditions of the joust are that if the Don loses, he must give up his foolish wanderings and go home. Well, he does lose — and how he loses — not only the duel, but his whole campaign against evil, his whole quest, his very knighthood. And so begins his tragic march home, during which his mind gradually clears; and by the time the old gentleman reaches home, stripped of his illusions and fantastic dreams, he is at last resigned and ready for death.

This beautiful death scene is Strauss' finale, one of the greatest things he ever wrote: because the music suddenly becomes incredibly simple, clear and full of repose; the solo cello sings out the last, which is the simplest transformation of the Quixote theme like a great prayer, and finally, in a long downward slide into silence, gives out its final breath. Then the orchestra plays a quiet cadence recalling the Don's great dignity, and the piece is over.

As you listen to these exalted final pages - try to keep in the back of your mind that there are two ways to think about all this. One way is that life is absurd to start with; that only a madman goes out and tries to change the world, to fight for good and against evil. The other way is that life is indeed absurd to start with and that it can be given meaning only if you live it for your ideals, visions and poetic truths, and despite all the skepticism of all the Sancho Panzas in the world, saddle up whatever worn-out horse you've got and go after those visions. Take your pick.

END

© 1968, Amberson Holdings LLC.

All rights reserved.