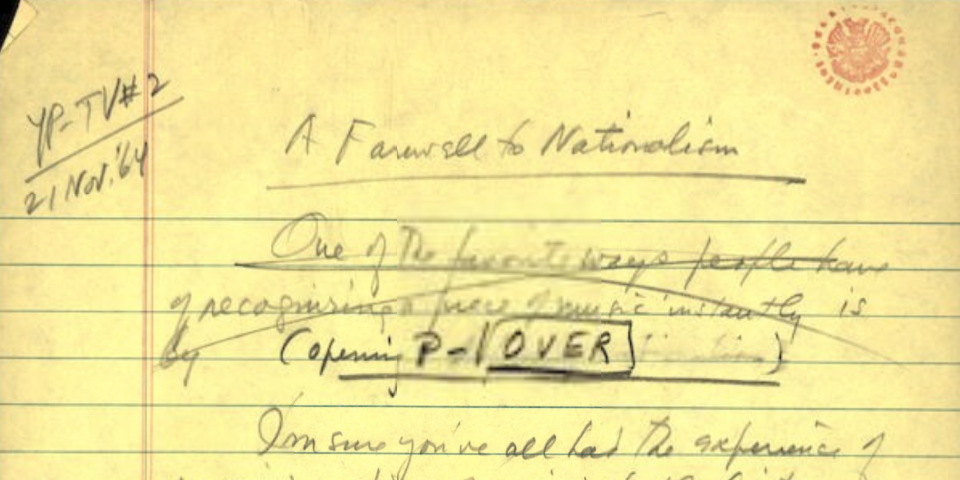

Lectures/Scripts/WritingsTelevision ScriptsYoung People's ConcertsA Farewell to Nationalism

Young People's Concert

A Farewell to Nationalism

Written by Leonard Bernstein

Original CBS Television Network Broadcast Date: 30 November 1964

Wow! You probably all know what that exciting little piece was - it's called the Russian Sailors' Dance from the ballet "The Red Poppy" by Gliere. But even if you didn't know it by name, I'll bet you recognized it as Russian music. And that's because it is so full of Russian folk spirit — folk melody, folk rhythm. In other words, it's what is called nationalistic music - that is, music that reflects the character of a particular nation, whether that nation be Russia, or France, or Peru, or the Navajo Indian.

For instance, if we play this bit of music, you'll immediately know it's - what? Try to guess.

What is it? [AUD. AD LIB] Try this one?

What is that? [AUD. AD LIB] Right! That's easy - obvious - everybody knew that. Spanish -- that's from a ballet by De Falla. Well, anyway, that's the way music used to be written, neatly packaged with clear nationalistic labels, and tied with colorful native ribbons. But I say "used to be" -- these days it's a whole other story. Especially since the last world war. The most recent music has been getting more and more international; in other words, it's becoming harder all the time to spot what country a really modern piece comes from.

For instance, see if you can tell the national origin of this:

Any suggestions? [AUD. AD LIB] No one brave enough to try? OK - It's German; although I don't know how you can tell, but amazingly enough, that was a complete piece by the famous and very influential Austrian composer Anton von Webern, written in the year 1913. Now, did you hear anything particularly German about that music? No. Probably not.

All right, another bit of music in the same style. See if you have any better luck with it.

Does that begin to sound any more German to you? It doesn't sound any more German than the first I take it. If it does, there's something wrong, because what we just played is not German at all, but a piece by a modern Japanese composer named Mayazumi.

Now how about that? If I hadn't told you that second piece of music was by a Japanese, you'd never have known, would you? You see, we've jumped 6000 miles from Germany to Japan, and the music has hardly changed at all. So something strange is going on these days, isn't it? Perhaps music is finally becoming what so many people have always liked to call it: a universal language.

Now, just for fun, listen to this bit of music, written in 1948 and see if you can tell what country it's from:

How 'bout that? Same problem again. It could be by a German, or a Japanese, or I heard someone say "Mars" before, but it happens not to be from Mars, it happens to be by an American named Milton Babbitt, a very gifted composer. Now here are a few bars from an Italian composer--his is just to complete our little world trip--a young Italian composer named Nono.

Again, that doesn't sound any more Italian than the Japanese piece did. Do you think so? No. Now, I don't want you to get the idea that all new music sounds like this, or that it all sounds exactly alike. It's just that the general trend these days is in the direction of an international style.

And I'm not saying that this is either good or bad; it's just a fact of history. With the world becoming smaller all the time, with news and fashions jumping over oceans in a matter of minutes or seconds even, with any spot on the globe just a few hours away by air from any other spot - it's no wonder that the world's music is becoming more and more alike. But there are lots of people who think that this is a pity; who long for the good old days when German music sounded German, when Japanese music sounded Japanese, and could always spot American music by its jazziness. Well, gone are the days.

Now I don't want you to fall into the other trap of thinking that all old music was nationalistic, any more than I want you to think all new music isn't.

Up to the 19th century, most music was more or less international in flavor - in sound. For instance, this is a bit of music by Bach, who as you know was a German

Now, here's a bit of music by Vivaldi, who as you know was an Italian.

Practically the same piece. Now even a musical expert would find it difficult to tell which of these two was German and which Italian, they sound so much alike. But once we come to the 19th century - ah, there we have another story. - Because those hundred years, from 1800 to 1900, were the time of the most tremendous nationalistic politics and spirit in Europe; and also most of the music we still hear today in our concert halls was written somewhere in that hundred-year period. So, if you put those two facts together, you get a third fact: which is that most of the music we hear today in our concert halls comes out of one fiery nationalistic feeling, or another, from the 19th Century.

Just think of some of the best-known 19th century pieces that we still hear in our concert halls today; like the prelude to Wagner's opera "Die Meistersinger."

Why that has 'Germany' written all over it: ponderous, earnest, well-nourished. German. And now the same thing is true of almost all the countries of Europe during that 19th century. This nationalistic feeling was everywhere. For instance, out of Poland came Chopin, who wrote his Polonaises and Mazurkas by the dozen, like this:

What else can that be but Polish music. And out of Italy came a whole slew of grand operas, marvelous operas, which are still today the mainstay of our opera houses, Rigoletto - Tosca - Pagliacci - Traviata: and all those famous tunes that you know, I'm sure.

That's Italian music; I mean, how much more Italian can you get? And then, of course, there's Russia, which was bursting with nationalistic composers all through the 19th century; Glinka, Borodin, Moussorgsky, Tchaikovsky - with pieces that went like this:

Russian music. Can't mistake it... written all over it.

So, in the same way, there was Granados and Albeniz in Spain, being very Spanish indeed; and in Czechoslovakia (or, as it was known then, Bohemia) there appeared Dvorak and Smetana, both fierce nationalists; and out of Norway came Grieg, and out of Finland, Sibelius, and out of Hungary, Liszt, and so on and on.

Even in our own America, which was born late and took a long time to get going musically, we had our own 19th century nationalists: MacDowell with his Indian suites; Henry Gilbert with his Negro and Creole Dances. And, by the way, let's not forget Ernest Schelling, the original founder and conductor of these Young People's Concerts, who died twenty-five years ago this month; and whom we are honoring for the great work he did with his concerts for young people, as well as for the proudly American nationalism of the music he wrote.*

But the greatest American nationalist of the time was certainly that strange and salty New Englander, whose name was Charles Ives, whose wildly original music has only recently begun to be known and appreciated. Ives was a part-time composer; you know he sold insurance for a living, and composed on nights and weekends; but somehow, in his half-amateur inspired way, he was able to produce music that was not only full of nationalistic American flavor, but music that also predicted many of the new, startling sounds that were later to become everyday stuff in what we now call 'modern' music. Ives was a pioneer and a prophet, and a patriot - a real old-fashioned American individualist, like Emerson and Thoreau. We are going to hear next one of his wildest and most original compositions, a very American piece called the "Fourth of July."

In this amazing work, we will be able to get a full picture of Charles Ives: including his fantastic invention of new sounds, bold harmonies, and mad orchestrations; and also his fascinating way with popular American tunes. In the space of this short piece we can hear snatches of more than half-a-dozen such ditties, ranging from the bugle-call 'Reveille' to 'Yankee Doodle' - and all mixed up together in a sort of dream-like far-out harmony. For it is a dream, this 'Fourth of July', — a boy's dream of that most exciting of all boys' holidays, in which sky-rockets are mixed up with marching bands and hymn-tunes, staying up late, and eating too much picnic food. And so all the familiar tunes come out slightly twisted, a little bit wrong, as they might be in a dream of long ago... Especially with indigestion.

For instance at one wild, climactic moment, you can hear the flutes are playing their version of 'Glory, Glory, Hallelujah. Sounds like this.

At the same moment, mind you, the cornets are blaring the first part at the same time, 'Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory.' That sounds like this:

AND at the same time the trumpets and the trombones are trying to top the others with 'Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean'

Now that's not just dream-like you understand; that's probably the way the local band actually sounded - [laugh] quite seriously - when Ives was a boy in the small town of Redding, Connecticut. They had a local band which I'm sure sounded like that and Ives was always trying to recall his own childhood and in this case he did it very graphically as you hear. It's part of that boyhood dream and it's associated with the fourth of July.

But even that's not all: at the same time, other instruments are trying to get through with 'Yankee Doodle'

Now somehow all those mad tunes go together, somehow, tossed around in a feverish memory of drums, fireworks, and church-bells:

Some dream! It sounds more like a nightmare. And to make it all even more peculiar, Ives has recorded for us that special sound of two bands playing at once. I'm sure you've all had the experience, during a parade, of hearing one band approaching as another disappears, each one is in a different rhythm.

Well, Ives actually makes this happen in the music, by splitting up the orchestra every once in a while into two orchestras; and of course for those moments we need two conductors, of course, to keep track of what's going on. So don't be surprised if now and again you find our assistant conductor, Seymour Lipkin, suddenly standing up and conducting away in a whole other beat. Mr. Lipkin...

This 'Fourth of July' by Charles Ives begins in the spooky shadows just before dawn. You'll hear little bird calls piping in the night, and even a rooster crowing for day. And then with the coming of day, the piece gradually builds up by piling one sound on top of another — a march, a hymn, church bells, fireworks, fifes, drums, and bugles — until the whole orchestra arrives at one final dissonant shriek, which is supposed to be the skyrocket going off above the town hall... looks as if the town hall is exploding, and then it all suddenly peters out in a few wispy notes, like waking up from a dream. You may not even realize the piece is over, the ending is so strange and sudden; so if you hesitate about applauding, Mr. Lipkin and I will understand.

Now that extraordinary piece by Charles Ives that we've just played was part of a 19th century movement in our country to compose American sounding music, somehow or other. Make it sound American. And this movement reached its peak in our own century with Gershwin, who as you know used jazz as the main nationalistic element in his music, instead of patriotic tunes, and with Aaron Copland, who used cowboy tunes and folk songs as his basic nationalistic element. But by the 1940's, the movement was over, not only in America, but all over the world. In Germany for example, the last of the great nationalists was, you know, Hindemith, whom you may remember we talked about last season, apropos of his death - and he is now dead, as is Mahler, who was the last great nationalist in Bohemia. In Spain, the last great one was de Falla, and he's dead; and in Hungary, it was Bartok - and he's dead. Even those great nationalistic composers who are still living are not being very nationalistic anymore, like the Russian Stravinsky, or the American Copland, who write in a rather international style these days. So, you see, times have changed; we're living now in an international world.

There are people who are convinced that a new period of nationalism is coming, especially in the music of the newer nations like Israel, and possibly the newly-emerging countries of Africa and Asia. It's possible, but at the moment we're still waiting. These days, audiences who love to hear music of a nationalistic kind still have to cast a fond look backwards to the last century in order to satisfy their nostalgia; so we're dependent on 19th century music. And so we're going to spend the rest of this hour playing two choice favorites from the good old days of nationalistic music.

Our first stop on this sentimental journey is Spain, and the music of Manuel de Falla.

We're going to hear a suite from his very famous ballet 'The Three Cornered Hat' - a light humorous work full of Spanish fandangos and flamenco spirit. This music is unmistakably Spanish. The moment you hear a rhythm like this you know you're in Spain.

That's absolutely Spanish - could be nothing else. Or a flamenco phrase like this which you'll here in this music

- or a dance tune like this one.

There's no mistaking what that music is, I'm sure you'll agree. Those are the Spanish materials out of which de Falla weaves his colorful, nationalistic tapestry. Now here are the dances from Part One of de Falla's ballet, 'The Three Cornered Hat'.

We're going to end our program on nationalism by playing for you in its entirety perhaps the most famous of all nationalistic tone-poems, 'The Moldau,' by the Bohemian composer Smetana. Into this endearing and enduring piece, Smetana has poured all the tenderness and pride of his love of country, and has produced this monument of patriotism which celebrates his native land by describing an imaginary journey down its most majestic river, the Moldau. You see, there are various ways in which a composer can pay homage to his country. Ives did it by a musical celebration of the Fourth of July, a great national holiday. De Falla did it by fashioning a large, beautiful ballet out of the folk-songs and dances of his native country. And now Smetana does it by celebrating the natural beauties of his country.

You've probably heard enough about this piece elsewhere to follow it without my giving you a road map: the lapping waves of the Moldau, the stormy rapids, the hunting scene, the wedding scene, the moonlight scene, and so on. I'm sure you'll recognize them all as you drift happily down Smetana's river; and as you drift, you should feel a warm, romantic glow from the nationalism that used to be.

END

© 1964, Amberson Holdings LLC.

All rights reserved.