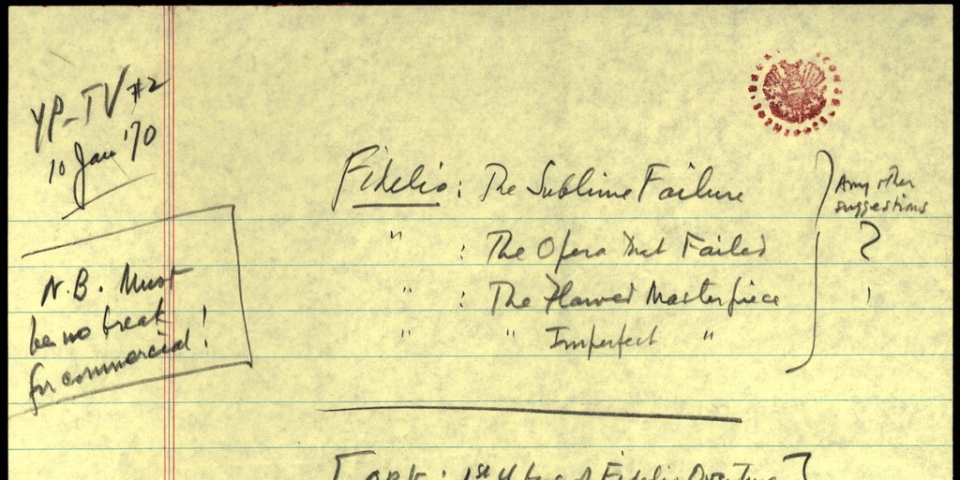

Lectures/Scripts/WritingsTelevision ScriptsYoung People's ConcertsFidelio: A Celebration of Life

Young People's Concert

Fidelio: A Celebration of Life

Written by Leonard Bernstein

Original CBS Television Network Broadcast Date: 29 March 1970

Now those famous bars proclaim the opening of Beethoven's one and only opera, Fidelio—one of his greatest works, containing some of the most glorious music ever conceived by a mortal, one of the most cherished and revered of all operas, a timeless monument to love, life, and liberty, a celebration of human rights, of freedom to speak out, to dissent. It's a political manifesto against tyranny and oppression, a hymn to the beauty and sanctity of marriage, an exalted affirmation of faith in God as the ultimate human resource. All of those, and more, are Beethoven's Fidelio.

And yet everyone will admit that, as operas go, Fidelio has its weaknesses. Some critics find it filled with flaws, and there are even those who call it a failure—a sublime bore. In fact, although it's performed day and night in German-speaking countries, it very rarely gets performed here in America. It's hardly what you would call a popular favorite like Carmen, or Aida. But then Beethoven never pretended to be an opera composer: He had never tried to write an opera before Fidelio, and he never tried one again. But the one he did try he gave his life's blood to. Imagine: He made three different versions of it over a period of ten years. He wrote and rewrote, he took out duets and put in arias, he changed spoken dialogue. He made up to eighteen different starts on one single number, and even wrote four whole different overtures to the opera before he was through. And after all that it remained imperfect, and still is to this day. A flawed masterpiece. But still a masterpiece, because when it's good, it's very, very good and when it isn't, it's still pretty wonderful. The truth is that Beethoven has become such a god-like image in our minds, that we tend to be extra-harsh and critical of him, when his music is the least bit short of absolute perfection. Besides the problems of the opera aren't so much musical ones as dramatic ones; that is, having to do with the play, and so I think the best way for me to explain them to you is to tell you the story of the opera very quickly, and you'll see what I mean even before we play a note of it.

It takes place in Spain, and the whole action occurs in a huge, gloomy state prison outside of Seville. (Imagine: A whole opera in a gloomy jail. That's a pretty stiff problem to start with.) The time is the end of the eighteenth century, just after the French Revolution. It's a time when everybody was concerned with freedom and political tyranny. The story, like all good old-fashioned plots, concerns a hero, a heroine and a villain. The hero is the nobleman Florestan, who has lo, these many years, been secretly and unjustly locked away in this prison for having spoken out bravely against tyranny, specifically against the wicked tyrant, Pizarro. Now Pizarro just happens also to be the governor of this prison, so naturally, it's the dungeon for Florestan. Well, there you have your hero and your villain. Now for the heroine. The heroine is Florestan's loving wife, Leonore by name, who spends the whole opera trying to get her husband free, and to do this she disguises herself as a boy, using the name Fidelio and thus getting a job as assistant to the jailkeeper—not to the wicked governor Pizarro, but to the nice little old jailkeeper. Keep that straight. Her assumed name of Fidelio is well-chosen since it means "the faithful one"—and Leonore is nothing if not faithful. Her one consuming obsession is to be reunited with her husband. Her plan is to pull an inside job; once she's in the prison working there, she thinks, she will find Florestan's secret dungeon—the deepest and darkest one in the prison, known only to the jailkeeper—and once she's found it, she can then help her husband escape. All this she does, brilliantly, and there is a happy ending.

Now that would all be fine and dandy as an opera plot, but there is unfortunately also a subplot. And that's where the trouble begins—with that wispy little subplot that involves the jailkeeper, his daughter and his daughter's boyfriend. Oh, the jailkeeper is a kindly, bluff old peasant-type named Rocco. He has a pretty teenage daughter named Marzelline, who is beloved by the equally young jailporter, whose name is Jacquino. Jacquino is trying to get her to marry him. But alas, Marzelline does not return his affection; because she has fallen for the new assistant, Fidelio, not knowing, of course, that he is a she. Now ordinarily such a set-up would produce a hilarious comedy of mistaken identity, awkward complications and lots of belly-laughs. But instead this little comic triangle gets mixed up with the noble, tragic drama of Florestan and Leonore, so that the subplot gradually gets lost in the shuffle, and finally disappears altogether. For instance, at the very end, when Florestan is finally freed and publicly reunited with his wife Leonore, and poor little Marzelline realizes with a thud that there's no such fellow as Fidelio at all, she's given one short line to express her surprise, "uh," and that's all. No pay-off. And as for poor Jacquino, he doesn't even get one line to express his surprise; he just sings along with everyone else in the triumphant finale. But we assume the two kids get together in the end and live happily ever after—but we'll never know for sure.

Well, that's the sort of dramatic problem Beethoven had to contend with. Now, of course it's not really Beethoven's fault, it's the playwright's fault. He's the one to blame; but these problems are unfortunately reflected in the music inevitably. You see, it's sort of two different operas stuck together. For instance, whenever we're dealing with the jailkeeper and his daughter and her boyfriend (that is, the subplot), the music is rather lightweight, charming, not very important. But the moment Leonore or Florestan step onto the stage; the music becomes sublime and on a par with Beethoven's most inspired creations. For example, here's the beginning of the duet between the two youngsters, Jacquino and Marzelline:

It's charming. It sounds rather like a comic opera by Haydn or Mozart, but not like a noble opera by Beethoven. Or take the opening of Rocco the jailkeeper's area:

Well, it sounds like.....Thank you, I really wasn't going to go for a hand on that one. But, you'll admit that sounds like a jolly enough German folk song, but it's not exactly what you'd call sublime music. And needless to say, it's the sublime music we're concerned with today, especially in this year of 1970 when we are celebrating Beethoven's two hundredth birthday. And perhaps the longest continuous stretch of sublime and dramatic music in the whole opera is that sequence of four musical numbers which opens Act Two: An aria, a duet, a trio, and a quartet, in that order. And that's the music we're going to hear now. I'm sure you'll see immediately what a world of difference there is between this magnificent music we're going to hear and the cute little bits we were just listening to. These four pieces are going to be sung in German by four unusually gifted young singers who are special post-graduate students at the Juilliard School, here in Lincoln Center. They are a great credit to its school, and to its new American Opera Center which is headed by the brilliant opera director, Tito Capobianco. The singers are, in order of musical appearance, Forest Warren singing Florestan, Anita Darian as Leonore, and Howard Roth as Rocco, and finally David Cumberland as the monstrous Pizarro.

And now to the music. We begin with Florestan's great aria — the opening of Act Two. The scene is that dark, dank, scary dungeon where Florestan lies in chains, wasting away, as he has for so many years. The long, mighty orchestral introduction to this scene is one of Beethoven's most powerful utterances, full of threat and pain and dark mystery. Out of this orchestral darkness rises Florestan's suffering voice: God, he sings, how dark it is, how horribly silent and dead! Then he tells, in a famous, noble melody, of how in his days of youth he had spoken out courageously for truth and freedom against the tyranny of Pizarro only to wind up in this filthy black pit. But he doesn't complain: He has done his duty, he is a man of honor and believes that God will help him. Then a marvelous thing happens: The orchestra quickens with excitement, and Florestan, in delirium, has a mystical vision of his beloved wife, Leonore, shining through the dark like an angel come to lead him to freedom.

It's almost a hysterical piece of music, one of the most difficult things ever written for the tenor voice, but luckily it lasts only a brief minute and again Florestan sinks, exhausted, down upon the deathly cold stones of his cell.

Now you understand what I mean by sublime music. But now, in order to understand what happens next, you must know that in the first act the cruel tyrant Pizarro has decided to murder Florestan in his cell, since he has just been tipped off that the minister of justice is about to pay a surprise visit to the prison—and Pizarro can't afford to have the minister find Florestan in his dungeon, because that would spill the beans, and Pizarro's own crime would be exposed. Can you follow that? I can barely follow it myself. However those were facts. And so he has bribed Rocco, the nice old jailkeeper, to prepare a grave for Florestan in an old abandoned well in his dungeon and once it has been dug, the plan is for Rocco to whistle a signal, and Pizarro will then slink in with his dagger, do the foul deed, and have Florestan buried before the minister can arrive. It's all a race against time, you see, and the suspense is tremendous.

So, in this next duet, we find Rocco descending into Florestan's infernal dungeon, spade in one hand, a lantern in the other, and accompanied by Fidelio (who, as you know, is really Leonore, in disguise). She has persuaded Rocco to take her along to help in the digging, on the grounds that Rocco is old and weak and needs assistance. As they enter the dungeon, we hear whispered dialogue between them: It's so cold down here, so dark—There he is!—I can barely make out his form—he seems dead—No, he's just sleeping—There's the well—Look, you're trembling, he says to her—No, it's just the cold, she says trying to be brave. And so the duet begins: Come on, dig, says Rocco, we have very little time. Yes, yes, answers Leonore, but inside she's praying: Give me strength to get though this: Let me set him free. Now all this is accompanied by a dark muttering in the orchestra, featuring the big double-bassoon which growls away in the depths.

That's Beethoven's kind of tone-painting—the deep, dark atmosphere of the place. You will also hear a wonderful bit of musical action-painting, as the two diggers labor to lift a heavy rock out of the debris in the well, and it's really quite a moment when the orchestra tells you that they've finally done it.

Up goes the rock! Now here come Rocco and Fidelio down the cold, sweating steps into the dungeon shadows.

Now, at this point, this dark, mysterious point, Florestan awakes, and Leonore sees with her own eyes that this starved, dirty unshaven skeleton of a man is indeed her husband. She recognizes him. He asks for a drink of water, and Rocco, moved by pity, gives the prisoner a little wine from his flask. Florestan is deeply stirred by this first humanitarian act he has witnessed in so many years having being treated like an animal, and in this spirit of almost religious holiness he begins the famous trio by singing his gratitude. And in the course of this trio Leonore produces a bit of bread she has been hoarding, and asks Rocco's permission to give it to the starving prisoner. Rocco finally reluctantly agrees, because it's strictly forbidden to give extra rations, but what's the difference he reasons? Florestan is about to die anyway; he might as well have a piece of bread. So she does give him the bread, and suddenly we're aware that we are witnessing a truly religious scene, where the act of giving the bread and wine becomes a Christian symbol of faith and salvation. Now here is that trio of compassion and love, and one might say Holy Communion.

God, that's beautiful stuff. It's very hard to speak even a word after that piece, but speak we must, for now the evil moment is at hand. The grave is ready, and Rocco whistles the signal. Enter Pizarro, cloaked and daggered; but like all great villains in old operas, old movies and plays and novels, he cannot simply kill: He must first have his sinister moment of triumph where he reveals himself to Florestan and gloats over his victim's imminent death and tastes the full sweetness of his own revenge. This is again one of those glaring dramatic flaws of which this opera is so full: You see, Pizarro knows that he's racing time, that the minister may arrive at any second, and yet he cannot resist milking his big moment. But then, when he finally does lunge for the kill, Leonore plants herself suddenly between her husband and the killer, shouting: Back! You must kill me first! Stab first this breast! The others are astonished: What?! Stop him! Take him away! Who is that person?! There is general consternation, topped by Leonore, on a high B-flat, singing: First you must kill his wife! What!? My wife? His wife? More general consternation. And Pizarro, by now wild with fury, lunges again to stab both of them when Leonore suddenly draws a pistol, shouting: One more step, and you are dead! And at that wildly dramatic moment, on the word dead, there is heard, off in the distance, the famous trumpet-call announcing that the minister has arrived. And there is a hushed moment of mixed emotions—wonderment, relief, anxiety, suspense all mixed together—and then again the trumpet call, nearer this time, louder. And now at last we are sure: Pizarro is foiled; the lovers are saved. The minister has arrived. And the quartet concludes with a thrilling coda, with Leonore and Florestan rejoined, singing jubilantly of their salvation, Rocco singing his relief, and Pizarro cursing his fate. It's a scene worthy of a Western thriller movie; but the amazing and magical thing is that with Beethoven's music it becomes so much more than that. It transcends our little earthbound sphere of heroes and villains, and it becomes something pure, abstract, sublime, and in the highest poetic sense, the triumph of good over evil.

END

© 1970, Amberson Holdings LLC.

All rights reserved.

Watch a video excerpt of "Fidelio: A Celebration of Life"

Leonard Bernstein rehearsing Beethoven's Fidelio with the Vienna State Opera Chorus and the Vienna Philharmonic, December 3, 1971. To be filmed by CBS for the program Beethoven's Birthday: A Celebration in Vienna with Leonard Bernstein.  https://www.loc.gov/item/musbernstein.100030253/

https://www.loc.gov/item/musbernstein.100030253/