Lectures/Scripts/WritingsTelevision ScriptsYoung People's ConcertsFolk Music in the Concert Hall

Young People's Concert

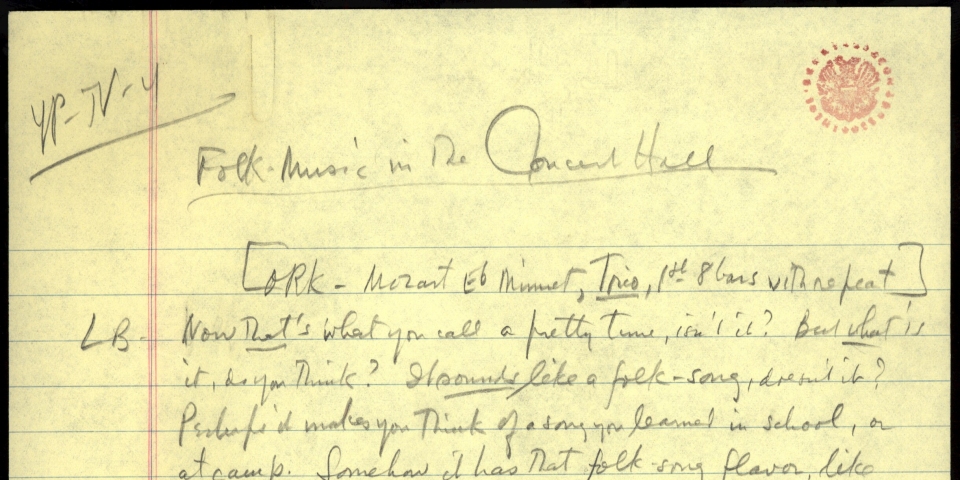

Folk Music in the Concert Hall

Written by Leonard Bernstein

Original CBS Television Network Broadcast Date: 9 April 1961

[ORCH: Mozart - Minuet in E-flat:Trio]

Now that's what you call a pretty tune, isn't it? Perhaps it makes you think of a song you learned in school, or at camp. Somehow it has that folk-song flavor, like something a lot of people might sing together, in a bus, or on a hike, or around the campfire. But it's not sung in any of those places: it's not even sung at all; it's played by a clarinet, as you just heard, and it comes from a symphony by Mozart, Maybe that surprises you — because it seems so simple and natural, not like the kind of complicated and grand stuff we usually think of as being in a symphony. But folk-songs and folk-dances are really the heart of all music, the very beginning of music; and you'd be amazed at how much of the big, complicated concert music we hear grows right out of them.

What is folk-music, anyway? Well you see, folk music expresses the nature of a people — you can almost always tell something about a certain people by simply listening to their folk-songs. Of course, most of the folk-songs we know belong to the past, when the different peoples of the earth were more separate from one another, and their characters and different natures were easier to tell apart. Sometimes these songs reflect the climate of a certain country; or they may tell us something about the geography of a country; or even tell us something about what the people do mostly, like being shepherds or cowboys, or miners, or whatever.

But most important of all, folk-songs reflect the rhythms and accents and speeds of the way a people talk, a particular people talks: in other words, their language — especially the language of their poetry — sort of grows into musical sounds. And those speaking rhythms and accents finally pass from folk-music into what we call the art-music, or opera or concert-music of a particular people; and that is what makes Tchaikovsky sound Russian or what makes Verdi sound Italian, or what makes Gershwin sound American.

It all comes from the folk-music, which in turn comes first of all from the way we speak. And that's the important thing we have to learn about today.

For instance, take a Hungarian folk-song that begins like this.

[SING: Hungarian folk-song]

Why do we know immediately that that's a Hungarian tune? (I mean, besides the fact that it's got Hungarian words.) It's because the Hungarian language has a strange thing about it: almost all the words in it are accented on the first syllable. Yoyon Hazak Edes Anyam. That's how you can always tell a Hungarian speaking English: he always says: "I don't UNderstand, BEcause I am HUNgarian." And that same accent naturally pops up in the music;

[PLAY: Hungarian folk-song]

— all the stresses BElong at the BEginning. And so it's just natural, when a great Hungarian composer like Bela Bartok writes his music, that he should compose in that same accent. Just listen to this tune from Bartok's beautiful "Music for Strings, and Percussion and Celeste.

[VIOLINS :Bartok - Music for Strings, Percussion and Celeste]

Do you see how that tune is like a string of words in a sentence, each one with a big accent at the BEginning on the first syllable? And that's not even folk-music anymore; it's already moved into the concert-hall.

But the same thing is true of all music; it grows out of a people's folk-music, which first grew out of their language. Look at French, for instance. French is a language that has almost no strong accents at all: almost every syllable is equal — not in length, but in stress, in accent. "Permettez-moi de vous presenter M. Bernstein." Now the minute you hear somebody say "PerMETtez-MOI de vous PREsenTER M. BERNstein" then you know he's no Frenchman. All the syllables have to be alike in stress. And these equal stresses show up just as clearly in French folk-music. Do you know this charming French folk-song?

[SING: Il etait un petit navire]

Do you see how equal all these syllables are? Just the opposite of the Hungarian song. Because it's all smooth and even.

[SING: Il etait un petit navire]

and that's exactly the smoothness and evenness that we hear in French concert-music, like this phrase from Ravel's "Daphnis and Chloe":

[ORCH: Ravel - Daphnis and Chloe]

And so it goes, through all the languages, Italian, for instance, is famous for its long beautiful vowels — Volare, cantare, oh, oh, ho, ho. And so Italian music lingers on the vowels. But Spanish, on the other hand, doesn't linger so much on the vowels; the consonants are more important: "Para bailar la bamba se necesita una poca di gracia y otra cosita"; and so the folk music comes out crisp and rhythmic, like the language:

[SING: La Bamba]

German, of course, is a very heavy language, with long words, and very long combinations of sounds: "Soll ich schlurfen, untertauchen, suss in duften mich verhauchen?" and so German music tends to be heavier and longer and more — well, self-important —than, say French or Spanish music. And as for English — well, that depends what kind of English you're talking about. English English is on thing; and the folk-songs from England are unmistakable — tripping and light, and quick with the tongue, just the way the British speak:

[SING: Strawberry Fair]

But now what kind of English is this?

[SING: Lone Prairie]

What is that? What kind of English is that? American. But what kind of American? Western. Right. Cowboy. And you see how different, how lazy and drawling the music is, too; completely different from the British. And just as different is the English of New York City, with its slap-dash syncopations, and its kind of tough charm:

[SING: jazz]

That's another kind of English, so it's another kind of music.

Well, all this is fascinating, but it still doesn't explain that Mozart tune we started out with. But that's easily explained. It's the middle part of the Minuet — the 3rd Movement — of Mozart's Symphony in E-flat; and the thing that makes that tune so enchanting is not that it's a folk-tune, but that it's like a folk tune. And Austrian this time. The melody has all the clean sweetness of Austrian Speech. And what's more, in the first part of the minuet you will also hear some of those Tyrolean hup-tsa-tsas that makes that folk-music so famous. You know those thigh slapping things that you get in the mountainous music of Austria. And so here is the whole Minuet now, real high-brow concert-music by Mozart, which could never have been written if the simple Austrian folk music hadn't come first.

[ORCH: Mozart - Symphony in E-flat - Minuet]

Now we're going to take a big jump, from Austria all the way to Mexico. And this will bring us even closer to real folk music — not just music that's sort of like folk music, as we heard in the Mozart minuet, but music that is really based on the old melodies and rhythms of the Mexican Indians. This is a short symphony, in one movement only, by the famous Mexican composer Carlos Chavez, and it's called Indian Symphony, or in Spanish, Sinfonia India. Perhaps the most wonderful thing about this exciting piece is the rhythms you'll hear in it — all kinds of rhythms, regular, irregular, in 2's and 3's and 5's and 7's and every combination. We're not dealing anymore with little French songs or British ditties or cowboy laments; this stuff goes way, way back to a very old Indian civilization — which we now call primitive. Of course, we have very little idea of what their language sounded like way back then, but we can almost tell by listening to this music: choppy, unemotional, almost wooden-like, Indian, in other words, primitive. But primitive music can be very thrilling, even if it's also quite limited. You see, it's usually just five notes —sometimes six — over and over again, the same five notes. Usually these.

[PLAY: pentatonic scale]

I'm sure you've heard all kinds of old folk music from all over the world that use those five notes:

Old Chinese music

[PLAY]

Scotch bagpipe music

[PLAY]

only those five notes. You can find it in African music or certain Hindu music, Malayan music, all over the place, and that's called a pentatonic scale. And here are the same five notes again, only this time they are Mexican Indian

[PLAY: Carlos Chavez - Sinfonia India]

That's the first tune from this Indian Symphony we're going to hear; and at first you might just say, so what? How boring to have to listen to the same five notes all the time, never changing! But that's just the wonderful part; Chavez takes these simple primitive scales and makes them not just interesting, but so exciting you want to jump out of your seat. And he does it through his imagination, by the way he puts the notes together, and by the marvelous rhythms he uses. Like this section at the beginning.

[PLAY: Carlos Chavez - Sinfonia India]

Of course a lot of the excitement comes from the way he uses the orchestra; he has a whole gang of Indian drums and rattles and strings and things. Like this:

[ORCH: Carlos Chavez - Sinfonia India]

And in addition to that he has a xylophone that seems to have a primitive life of its own, which keeps going on no matter what the rest of the orchestra is playing with this:

[XYLOPHONE: Carlos Chavez - Sinfonia India]

And then there are very strange shrieks and whistles that occur in the woodwinds:

[FLUTE & PICCOLO: Carlos Chavez - Sinfonia India]

Of course, there are also some lovely melodies that Chavez makes out of his five or six notes: in fact there's one you may all go out whistling. And there's a dance at the very end that builds up to such a pitch of excitement by repeating and repeating, that I wouldn't be surprised to turn around at the end and find you all swinging in the aisles. Her is the Sinfonia India by Carlos Chavez.

[ORCH: Carlos Chavez - Sinfonia India]

So far we have heard a Mozart Minuet that is not folk-music, but has a family resemblance to it; and a Mexican symphony that uses real folk music rhythms and notes, but no actual folk melodies; Chavez wrote all those tunes himself. But now, at last, we are going to hear real folk songs, preserved just as fresh as the day they were born in that ancient region of France called the Auvergne. Even the language they are sung in is the same old dialect, part French, part Spanish, part who knows what, that the shepherds and peasants spoke in those mountains there centuries ago. These songs from the Auvergne have been collected for almost 40 years by a French composer named Canteloube, who has a special passion for the folk music of his country, and who has arranged orchestra accompaniments for them that are as beautiful and touching as the folk songs themselves, Now I have the great pleasure of presenting to you Miss Marni Nixon, a beautiful young soprano, who will sing three of these songs for you.

[ORCH: Canteloube - Chansons d'Auvergne L'antoueno]

MARNI NIXON:

That last song was a love song sung by a young farm girl to her lover. In the next song, the same girl sits down to her spinning wheel and spins and she says, "When I was a little girl I used to watch the sheep." And then she spins a little and she makes fast, little spinning sounds: Ti lirou lirou lirou lirou. Then she says, "There was a shepherd who helped me watch the sheep. He asked me for a kiss and out of gratitude, I gave him two." Then she spins again and says, "Ti lirou lirou lirou lirou."

[ORCH: Canteloube - Chansons d'Auvergne Lo fiolaire]

And the last song is a bit of carefree philosophy. It says:

Unhappy is the man who has a woman,

Unhappy is the man who doesn't have a woman,

And he who has a woman, doesn't want one

And he who doesn't have one, wants one.

[ORCH: Canteloube - Chansons d'Auvergne Malurous qu'o uno fenno]

LEONARD BERNSTEIN:

And now we're going to hear a marvelous piece that sums up all the things we've been talking about — a piece with the folk-spirit of the Mozart Minuet, the folk-material of the Chavez Symphony, but also real folk-tunes quoted as exactly as those folk songs of the Auvergne that we've just heard. It's an American piece this time by a salty old Yankee named Charles Ives, who lived, up to his death a few years ago, in Danbury, Connecticut. He was one of the first American composers to use folk songs and folk dances in his concert music. It was his way of being American to take marching tunes and hymns and patriotic songs and popular country fiddle music and develop them all together into big symphonic works. The piece we are going to hear is the last movement of his Second Symphony and before it is finished you will have heard tunes that sound like barn dance music, and tunes that sound like Stephen Foster melodies, Swannee River, tunes that sound like fife and drum music; but more than all this, you also hear real barn dance tunes like "Turkey in the Straw" which you all know

[PLAY: Turkey in the Straw]

and real folk songs such as "Long Long Ago"

[PLAY: Long Long Ago]

and a real Stephen foster tune - "Campton Races"

[PLAY: Campton Races]

and a real bugle call - "Reveille"

[PLAY: Reveille]

and to top it all off, a long quotation from that grand old American tune — "Columbia the Gem of the Ocean"

[PLAY: Columbia the Gem of the Ocean]

which I guess you know too.

It all adds up to a rousing sort of jamboree, like a Fourth of July celebration, finished off at the very end by a wild yelp of laughter by the whole orchestra made by playing a chord of all the notes in the rainbow at once like this:

[ORCH: chord]

That's the finish, as if to say — Wow! It's a perfect piece for ending this series of programs which have been very exciting for us to present to you. We hope you found them exciting too, and we're happy to say we'll be back with you for another series next year. And now ... Here's the final movement of the Second Symphony of Charles Ives.

[ORCH: Charles Ives - Second Symphony]

END

© 1961, Amberson Holdings LLC.

All rights reserved.