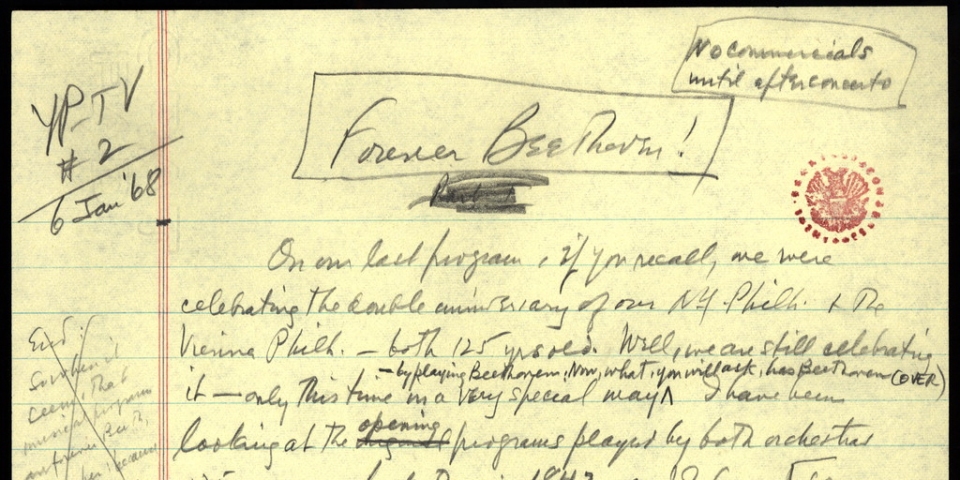

Lectures/Scripts/WritingsTelevision ScriptsYoung People's ConcertsForever Beethoven

Young People's Concert

Forever Beethoven

Written by Leonard Bernstein

Original CBS Television Network Broadcast Date: 28 January 1968

LEONARD BERNSTEIN:

My dear young friends: On our last program, if you recall, we were celebrating the double anniversary of our New York Philharmonic and the Vienna Philharmonic both 125 years old. Well, we are still celebrating it - only this time in a very special way - by playing Beethoven. Now what, you will ask, has Beethoven got to do with our anniversary? Well, I'll tell you. I have been looking at the two opening programs played by the two orchestras way back there in 1842, and I found one striking similarity between them: the name Ludwig van Beethoven is all over the place. Almost half of all the pieces played by both orchestras were by Beethoven. He had the market cornered; this was a mere fifteen years after his death.

But what's even more remarkable is that today he's still by far the most often played symphonic composer that ever lived. He still has the market cornered. An all Beethoven concert is an every-day occurrence, isn't it. And what is the main piece on every piano recital? A Beethoven sonata. And during the last world war, what was our musical symbol for victory? Pah-pah-pah-PAH. Morse code 'V' for victory, which as you know is Beethoven's Fifth. And when a great man dies, what do we play? The funeral march from Beethoven's Eroica. And on United Nations Day, or Brotherhood week, or whatever it happens to be, what is the inevitable piece of music? Beethoven's Ninth. Why, even the Beatles featured it in their film "Help." And look at Schroeder in Peanuts; To him Beethoven's birthday is more important than the 4th of July. It's Beethoven, Beethoven, forever Beethoven -it's name that's almost become a synonym for music itself.

And who was this giant with the magic name? Well, he was short, stubby fellow, not Viennese at all, not even Austrian, but German, from the town of Bonn on the Rhine River, where he was born in 1770. And how did he get to Vienna? At the age of 22 he was sent there by the local big-shots of his home town, since Vienna was the place for studying music and making a career.

And so this little provincial chap with bad skin and a comedy accent from the Rhineland arrived in Vienna, knocked them all dead, and was taken up by the Viennese nobility and made a hero. Before long he was dominating the musical scene, which he has continued to dominate ever since - the mighty, the colossal, the profound, the revolutionary, the mystic, romantic Beethoven. He was also, you should know, bad-tempered, stubborn, ill-mannered, messy, arrogant, moody, and miserly. But out of this homely human, and a defective one at that, since he had grown deaf by the time he became 32 - out of this human vessel spoke a voice that was more than human - a voice with the ring and the conviction of something eternal, something that still today makes us tingle with a sudden awareness that a divine spark exists in every one of us.

Now why should this be? I've been trying all my life to find out.

The very first television program I ever did was about Beethoven. The very first chapter of my first book is called "Why Beethoven?" Well, I'm still asking that question, and I will probably never find a total answer. Mighty, colossal - those words just don't explain anything. Because the final answer is a mystery - the mystery of why this one particular, grubby, shaggy-headed little man should have been chosen to wallop the galaxies with his music. And so we shall have an all-Beethoven program today, beginning, just as we began 125 years ago, with those four heaven- storming notes that announce the first movement of his Fifth Symphony.

Still the most fantastic music no matter how often you hear it. Did you grasp the shape of that movement? The perfect definition, the exactness, of starts and stops, of holding back and plunging ahead, of the sudden mysterious drops and the wild eruptions? Every split second is measured and molded by a master.

Now apropos of this shaping, and molding there is an important thing that needs to be said, and I'm going to try to explain at the risk of boring you with a tiny lecture. You've probably heard of a popular biography of Beethoven called "The Man Who Freed Music." Now this title has always caused me a certain disquiet. Because, what does it mean? Freed music from what? From Bach? From Mozart? Haydn? Well hardly: I mean they all had plenty of freedom of their own.

The truth is that all great composers free music - not from the bondage of other composers, but from routine, from mediocrity, from second-rate, dusty tradition; in other words, a great composer frees music from the predictable. Now take one of Beethoven's most obvious examples of the unpredictable - the famous opening tune of his third Symphony, the Eroica. Now you know that tune. It rides along in E-b major on the nice, expected notes of the tonic triad

it goes like that for four bars, on just those notes, and then, on the fifth bar, the unexpected happens so the tune goes like this:

Bang! - That D-b! Surprise: the bondage of the triad is broken. Music is freed. But freed by what? By a Db and that's just the point: it's a Db, not a Cb and not by an A natural but that one, chosen, limited note, Db - that's what did the freeing.

Now doesn't this tell us something very important about the nature of freedom? Obviously freedom must carry with it the meaning of freedom to limit oneself, and one's material. Freedom is not infinite, not boundless liberty, as some hippies like to think - do anything you want, any time, anywhere you want to. No, freedom isn't that. It means being free to make decisions, to determine one's own course. But deciding means choosing and choosing is impossible without rejection. Can you understand that? You can't choose something without rejecting all the other things you haven't chosen. If you choose one apple out of a dozen, you automatically unchoose the other eleven, and Beethoven chose that one D-Flat, he automatically un-chose all the other eleven notes.

So you see, real freedom must contain within itself the freedom to un-choose as well as choose, to censor oneself to limit oneself. That is the whole meaning of democracy, the kind freedom on which we base our hopes for a peaceful world - just as it is the meaning of freedom in great musical composition. In Beethoven, as in democracy, freedom is a discipline, combining the right to choose freely, with the gift of choosing wisely. Now do you see what I meant by Beethoven's shaping of that movement? I hope so!

End of lecture.

Now we are going to hear more of that great free discipline in action — the last two movements of Beethoven's Fourth Piano Concerto in G major. Now the first of these is the brief but marvelous slow movement which has often been compared to Orpheus taming the beasts with his legendary musical powers - the beast in this case is of course the orchestra which is loud and angry and rough, and Orpheus is the solo piano - soft and tender, in this dialogue as the movement progresses the orchestra is gradually reduced to a domesticated whisper. And then everything ends in a happy rondo. Our Orpheus today is a young artist who has the depth and power to match this music - a 21-year old Israeli named Joseph Kalichstein.

And he will be accompanied by one of our young assistant conductors, Paul Capolongo, a very gifted young Frenchman, who was born and raised in of all places, Algiers. How wonderful that Beethoven's music can bring together an Algerian and an Israeli. And here they are --

A little before that gorgeous piano concerto, we were talking about the connection between Beethoven and freedom; and nowhere is that connection more evident than in Beethoven's opera Fidelio. This was the only opera Beethoven ever wrote, but he wrote it and rewrote it and rewrote it over a period of twelve years. This, of course, was typical of Beethoven in his search for perfection; all his works went through long agonies of rewriting and scratching out and trying again -that was the price he paid for his freedom, the price of free choice - to make the exactly right choice. But, with his opera Fidelio the agony was even worse, and I think one of the main reasons was that the story of the opera deals with the very subject of freedom itself. The hero of the story is a young Spaniard named Florestan, who has nothing to do with toothpaste, but has been unjustly imprisoned for speaking out freely against tyranny.

CFlorestan's loving wife, whose name is Leonore, has managed to sneak into the prison disguised as a boy, and gets a job as the jailor's assistant so that she can help her husband escape. So there you have Florestan and Leonore. Now why in the world is this opera called Fidelio? Because that is the name Leonore takes in her disguise as a boy.

And even here, with the title Beethoven wrestled with his freedom of choice. Because the opera was first called Fidelio, then changed to Leonore, and then back again to Fidelio. And the overture to the opera most clearly of all reflects the agony of free choices. Beethoven was not satisfied until he had written four different overtures to this opera. Three of them are called Overture to Leonore numbers 1, 2, 3, respectively and the fourth is known as the Overture to Fidelio. Don't ask me to explain why, it's too complicated - but of all four, it is the 3rd Leonora Overture that is the masterpiece, and the one we are going to play now. This is a massive work - more than just an overture, rather more like a great symphonic poem describing the whole opera.

During its slow introduction we feel the heavy, brooding atmosphere of Florestan's dungeon. And then, when the main fast section begins, we hear the gradually rising hope of rescue surging up through the orchestra, and the excitement is made even more dramatic by alternating with moods of prayer and of love music. At the climax the orchestra suddenly cuts off, and the famous trumpet-call of liberation sounds in the distance announcing the arrival of the rescue party (You'll hear it coming from somewhere backstage there); then there is a moment of hushed suspense, then again the trumpet-call, nearer this time, and finally the it arrives, the triumphant achievement of freedom, in a brilliant coda of celebration. As you listen now to this essay on liberty, you can understand why Beethoven has always meant so much to us and will continue to. As long as the human race struggles for freedom.

END

© 1968, Amberson Holdings LLC.

All rights reserved.