Lectures/Scripts/WritingsTelevision ScriptsYoung People's ConcertsHolst: The Planets

Young People's Concert

Holst: The Planets

Written by Leonard Bernstein

Original CBS Television Network Broadcast Date: 26 March 1972

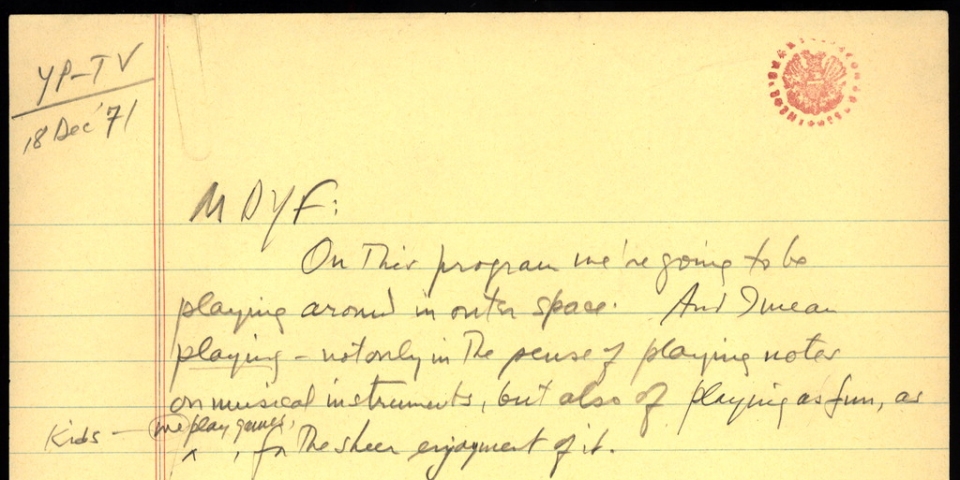

LEONARD BERNSTEIN:

My Dear Young Friends: On this program we're going to be playing around in outer space. And I mean playing — not only in the sense of playing notes on musical instruments, but also of playing as fun, as we play games, for the sheer enjoyment of it.

Now these days when we think of outer-space music, the first thing that pops into our minds is that well-known fanfare:

(LB sings next two notes)But that is, of course, the opening of Zarathustra by Richard Strauss, which we learned about in such depth last season, and so we know it doesn't really have anything to do with outer space. Then there's what's sometimes called "spaced-out" music like certain rock music or pieces by Stockhausen, but they really have to do with the inner spaces of our minds.

But today we're going to hear a piece called The Planets by the British composer Gustav Holst — and this does have to do with outer space, because that's literally what it's about; The planets of our solar system. And the reason I call it music for fun is that it doesn't try to make any deep philosophical points, it doesn't tell any complicated story, it doesn't try to blow your mind with new musical techniques — it's just great first-class entertainment. In fact, when it was first played in Germany around 1920 some critics roasted it as being nothing but "Unterhaltungsmusik" — which means "entertainment music," Well, what's wrong with that? Especially if it's good; and If it turns out to blow your mind, which it might — so much the better.

It's a big piece; after all, there are an lot of planets to cover, and each planet has a whole piece of its own. And so, correspondingly, Holst uses a big orchestra, a very big one, in fact, as befits so large a subject as the solar system.

He's not satisfied with the 100-odd pieces of the normal big symphony orchestras; he calls for extra added instruments, not ordinarily used, like a bass oboe:

Now it may surprise you to learn that Holst's Planets are seven in number: that is, there are seven movements. How come seven, when every child knows that there are nine planets moving around the sun? Well, the answer is that, first of all, at the time Holst composed this work, over 50 years ago, the 9th planet, Pluto, had not yet been discovered, so there were only eight. And second of all, he left one out that we consider pretty important — namely, Earth. Which leaves us with seven planets: Mars, Venus, Mercury, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune.

But why did he leave out, of all things, our very own planet Earth? That's an interesting question. The answer, of course, is that Holst wasn't at all interested in astronomy, but in astrology. I'm sure you know the difference. Now we all know that in astronomy the sun is the center of our system, and we all revolve around it; but in astrology the Earth is the center, and everything else revolves around us, including the sun and the moon.

So out went Earth as a planet. It's not very scientific but Holst couldn't have cared less about the scientific side of the planets, he was drawn to the mystic side of things, and for him the planets were important as symbols, in relation to the zodiac, to horoscopes, to the ancient sort-of-science known as astrology. I suppose today he would be called a mysticism-freak. One of his pet hobbies was drawing up horoscopes for his friends, not so much to predict the future, as to try and get a fuller idea of their character and personality. And this is just what Holst did with his planets. He would pick on one aspect, or personality, of each planet, and write music about it.

Now it's not that easy to pick: one single aspect of any planet — astrologers have been arguing for centuries about the real meanings and influences of these strange wandering bodies. But for Holst it was easy; he just decided what each planet meant to him, and went to work.

So out came planet No. 1, Mars, which he subtitled, the Bringer of War. It presents an amazingly realistic picture of war: the racketing of machine guns.

The grinding of monstrous tanks

plus fanfares and marching and screaming, and all the rest. Here is that first planet Mars, the Bringer of War.

Now that may be an exciting piece to hear, but it's not exactly beautiful music; in fact you might even call It ugly music. But then, what is uglier than war? And this music is not so much an impression of the planet Mars — with its red glow, and its possibility of life — as it is an impression of Mars the god of war, after whom the planet was named. It's an inhuman piece, utterly mechanical, brutal and relentless. Just like war itself, inhuman, brutal, relentless and mindless. But just think a minute: if an artist sets out to depict something ugly, in notes or paints or words, and if he does it well, doesn't that make beautiful art? (Think of Breughel) of the ugliness in Picasso's Guernica, the unpleasant scenes in drawings by Goya, the distasteful subject matter in Dickens, and Dostoevsky. Aren't those all beautiful works? There's something for you to ponder over a hamburger some time.

But meanwhile, as an antidote, Holst brings us his second planet, Venus, the Bringer of Peace.

Now that's sort of a surprise; we usually think of Venus as the goddess of love; but astrologers have made her a symbol of peace by a simple equation: love equals harmony, and harmony equals peace. Easy.

So here is Venus, a very different story from Mars: This is music of humanity, of rich harmony and gentle movement. In short of peace.

We're going to play the next two planets together, without pause, because they're short, and somehow belong together. The first is Mercury, described by Holst as the Winged Messenger. Which, of course, the Roman God Mercury was, swift as lightning, swift and small. And so is the music. Actually, the planet Mercury is the smallest of all and being the closest to the sun it has the shortest orbit; so naturally it has the shortest musical run as well. But that's astronomy again, which wasn't the name of Holst's game. What he cared about was that astrologers have always described Mercury as a quick tricky type, double-dealing, now-you-see-him-now-you-don't. And Holst makes this point by writing double-dealing music — for instance, by writing in 2 different keys at once. Here's one harp playing in Bb major:

and the other harp in E major:

And the whole orchestra follows suit. To make the two-faced point even stronger, Holst writes in 2 different rhythms at once: like here's a clarinet playing in 6/8 time:

and against that the bassoons are playing in 3/4 time:

And together they sound like this:

You see what I mean "by double-dealing? Mercury is a very elusive little creature.

One other little trick: since Mercury is the messenger of the gods, and astrologically in charge of messages and communications, Holst tells us this by inventing a little passage of what seems to be Morse Code:

This is later repeated by the Glockenspiel:

I've always suspected some secret message in this music, but I've never been able to discover what it is. Maybe some Morse-code expert among you out there can decipher it.

Anyway, that's Mercury. And his companion is his exact opposite — Jupiter, the hugest planet of all, the master, the chief god. Holst calls him Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity -- but that seems a very small attribute to assign to so great a planet. The astrologers say that Jupiter brings power, wealth, high position, fatherhood, ownership — everything big. Also jollity — I suppose because the Romans also called him by the name of Jove, from which we get our word jovial.

And to Holst, that was the most important of all — joviality, or jollity, and in the most British manner — the ho-ho jollity of Santa Claus, of John Bull, of roast-beef and Yorkshire pudding. This is the most famous of all Holst's planets, and even contains a lot of famous jovial tunes you'll recognize from TV commercials and stuff like that.

So now, here they are together, these total opposites, little Mercury and big Jupiter, the messenger and the master, the servant and the lord, the naughty little boy and Big Daddy.

Well, that leaves us with three remaining planets, and not enough time to play them all. The next in line Saturn, the Bringer of Old Age, seems like a good one to skip, since it's long and slow and draggy, and who wants to think about old age at this moment anyway? Besides, the astrologers tell us that Saturn is a nasty-planet, always making trouble for us mortals. So on to the next planet, Uranus, which Holst calls the Magician. Well, again, that's only one astrological side to this strange planet: it is supposed to control all kinds of sudden changes, reforms, inventions, revolutions. And what is so interesting to us in this revolutionary day and age is that Uranus is linked to the sign of Aquarius, and Heaven knows we never stop hearing about how we've entered the (Age of Aquarius.) But of course Holst never saw "Hair", so as far as he was concerned, Uranus meant magic to him. And in his music he makes a delightful picture of a magician— in fact, the music is at times very reminiscent of "The Sorcerer's Apprentice"

But that's not all there is to it. This magician struts about, pulling off one surprise after another, and finally breaking into a triumphant march:

Say: Come to think of it, that's not a bad tune for the Age of Aquarius:

Well, maybe not. Anyway, the magician has one final trick up his sleeve, where the music abruptly goes soft and way-out, and we suddenly are in outer space. I think you'll know it when we come to it. Here's Uranus, the Magician:

And now we have a surprise for you, and for Holst too, if he's listening somewhere out there in the Universe. Instead of playing his final planet, Neptune, which is also long and slow, the New York Philharmonic and I propose to supply the missing planet, Pluto. You remember I told you that Pluto had not yet been discovered when Holst wrote this work; but it was discovered in 1930, when Holst was still alive. So he had his chance to add Pluto to this work, but for reasons of his own didn't. So we're going to make up for this omission by supplying a little Pluto of our own.

As you know, Pluto is the furthest planet from the sun, and therefore the darkest and the most mysterious. Very little is known about it, except that it is very dark, and very slow-moving, with an endlessly long orbit. It is also the bane of the astrologers1 existence, because suddenly there it was in 1930, upsetting all the calculations of centuries, and causing no end of confusion in the world of horoscopes.

With all this in mind, we shall now attempt to shed a little light on this dark planet by improvising a Pluto-piece. Let's call it in the manner of Holst, Pluto, the Unpredictable; but there any resemblance to Holst will end. This music will not be in Holst's style, nor in anybody's style for that matter, because we don't know what's going to come out. We have no pre-arranged signals, and we here on stage are going to be as surprised as you at the mysterious sounds we will be making. In other words, you are about to hear a piece nobody has ever heard, nor will ever hear again. It's a once-in-a-lifetime experience, a real spaced-out trip. And here it is: Pluto the Unpredictable.

END

© 1972, Amberson Holdings LLC.

All rights reserved.