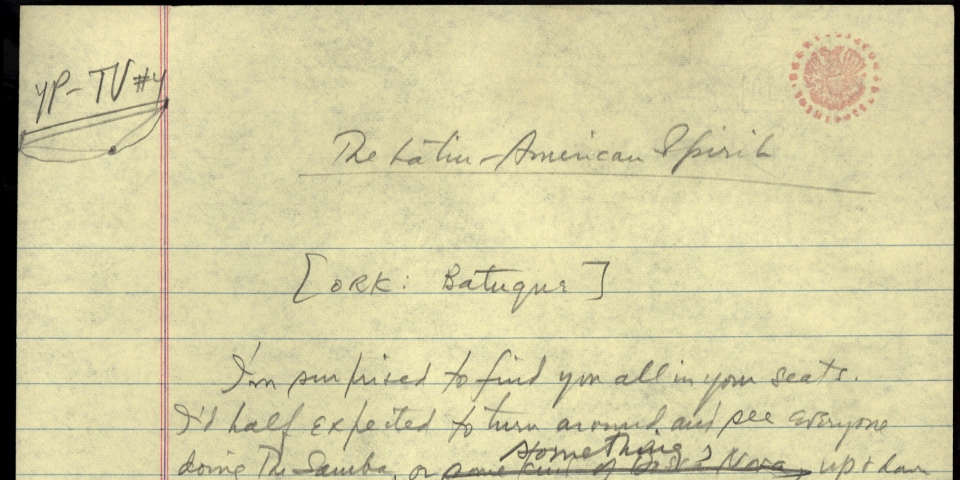

Lectures/Scripts/WritingsTelevision ScriptsYoung People's ConcertsThe Latin American Spirit

Young People's Concert

The Latin American Spirit

Written by Leonard Bernstein

Original CBS Television Network Broadcast Date: 8 March 1963

I'm surprised to find you all in your seats. I'd half expected to turn around and see everyone doing the samba, or something, up and down the aisles. This Latin American music is almost irresistible, when it's good, like the "Batuque" we just heard, by the Brazilian composer Fernandez. It has a way of stirring up the blood, not only our North American blood, but people's blood all over the world. Ever since I can remember there's always been an international craze of some kind for Latin American dance music, from the old Argentine tango, which swept the world in my childhood, all the way through the rhumba, the samba, the conga, the mambo, the cha-cha, the pachango, the merengue, right up to the present excitement over something called the Bossa Nova.

What is it that makes this music from South and Central America so exciting? Well, there are two ingredients that give this music its special Latin flavor: rhythm and color. The first of these, rhythm, doesn't mean just the beat, that insistent, obsessive beat, but the complicated rhythms that go on over the beat. For instance, in this Batuque we just played, you heard a fascinating beat that went:

which is already pretty exciting, not only because it keeps repeating insistently, but because it has that syncopated accent: 1, 2, 3, 4, 1, 2, 3, 4. Now, I'm sure a lot of you remember what syncopation means from other programs of ours we've given; a syncopation is an accent that falls where it doesn't belong, or where you don't expect it: 1, 2, 3, 4, 1, 2, 3, 4. You expect it on one, and it falls on four. That's exactly what happens in this Batuque beat.

But over that syncopated beat there are rhythms that are even more syncopated and more complicated like this one.

So, what with one syncopation and another, it turns into a pretty hectic boxing match with sudden lefts and rights hitting you where and when you least expect them. And that, plus the insistent repetition of the beat, explains why you want to get up and dance when you hear this kind of music.

The second element that we find so attractive in Latin American music is all that special instrumental color. It's unmistakable. You're never in doubt about what kind of music you're listening to the moment you hear, for instance, this colorful little sound:

Now that's a pair of maracas, and what's a rhumba or a samba without a pair of maracas? The same is true of that well-known dry little sound you get from hitting two sticks together—what the Cubans call "claves"

And then there are all kinds of gourds, like this,

and rasping sticks,

and an endless variety of other things like conga drums and bongos that make the music sound Latin.

Now actually I'm not crazy about that word "Latin" to describe this kind of music, because it tells only part of the story. When we speak of "Latin America" we are, of course, referring to the historical fact that these countries were conquered, settled, and exploited by invaders from Latin countries: like Spain—or, as in the case of Brazil, from Portugal. That's why Spanish and Portuguese are still the official languages of our friends to the south of us: and those languages are called "Latin" languages because they developed from the old language of ancient Rome.

But the Latin American spirit—which is our subject today—has other ancestors besides the Latin ones, at least as important; and they are first of all the Indians,—the original inhabitants of those countries, and in some cases very strong civilizations in themselves—and secondly, Africans, a tremendously important influence, at least as important as it is in our own country. And it is the mingling of these different ancestors, influences, and heritages, which makes the Latin American spirit, what it is at any rate in the music.

But we mustn't begin to think that all Latin American music is only cha-cha-cha-cha dance music—not by a long shot. Our Latin neighbors have produced an impressive number of serious symphonic composers, who have succeeded in preserving the folk flavor of their own countries, while at the same time expanding their music into what we think of as universal art—music that has not only a nationalistic spirit but the spirit of all mankind. Certainly the most admired of all these composers was the great Brazilian Villa-Lobos, who died only three years ago, leaving many beautiful compositions; and we're now going to hear the most famous one—the Bachianas Brasileiras No. 5. Now that's a mouthful of a title; but it's simple to understand: Bachianas simply means "pieces like Bach"—the great German composer Bach—in other words, "Bachian" pieces; Bachianas in Portuguese and Brasileiras means Brazilian, naturally, and #5 means that he wrote almost a dozen different words using this title, of which this is the 5th; so there you have it, Bachianas Brasileiras No. 5. Now what is Bach doing in Brazil? Well, that's just the point of this piece, and really the point of all the pieces Villa-Lobos composed: he wanted to bring together his native folk-lore elements with the great European musical tradition, and unify them into a single style of his own, as he does in the very title of this piece - Bachianas Brasileiras. And it's amazing how well he succeeded, as you will hear, especially in the first movement.

There are two movements in this piece, which by the way is written for a soprano voice and an orchestra consisting of nothing but eight cellos! Now in the first movement, which is slow and tender, he has the soprano sing a long, melodic line, without words—just the syllable Ah.

And underneath, the eight cellos accompany this Bachian song like one huge guitar. Then there's a short middle part, that does have words, in Portuguese, about the moon; but then the singer goes back to the wordless Bachian melody, only this time, instead of singing Ah, she hums it.

Altogether it makes a haunting, unforgettable atmosphere. Then comes the second movement, which is much more Brazilian than Bachian—a fast, gay, tongue-twister that does sound like a native folk-dance. And this difficult and fascinating work will now be sung for us by the brilliant Israeli soprano, Netania Davrath.

Well, so far our music has been all Brazilian, which seems natural since Brazil is the largest Latin American country; but I don't want to give you the impression that it's the main source of Latin American music. Every single Latin American country, without exception, has produced fine, serious composers, from Mexico to the tip of Chile. But perhaps Mexico and Cuba have been in the lead, possibly because of their closeness to our musical centers, or possibly because they have such great international cities of their own. Actually our next piece of Latin music, strangely enough, comes from both countries, since it was written by a Mexican composer, named Revueltas, but was based on a poem by a Cuban, named Guillen. It's a poem in which he remembers Africa and African tribal rituals, a weird sort of chant about killing a deadly snake. But this strange and terrifying piece, which is called Sensemayá, combines all the influences we spoke about—African, and Indian, and European. You see, it's the work of a sophisticated composer, with a very advanced technique, like Villa Lobos, but he's handling an idea of savage primitiveness. And all that savagery and violence is to be heard in the wild rhythms and shrieks and howls of the orchestra that you will hear—but they are all controlled by the knowing hand of a real artist. It's much more complicated, more syncopated, more difficult than either of the pieces we have heard so far. You see Revueltas was a real artist, who died tragically young, at the age of forty; and to judge by this short but thrilling piece we are now going to hear, he might have achieved true greatness, if he had lived. Here is his African-Indian-Cuban-Mexican poem for orchestra, Sensemayá.

For the second part of our program, we're going to turn the tables, and salute Latin America by playing music written by North American composers under the influence of Latin American. As I said before, we've always been enchanted up here by those Latin colors and rhythms, which have crept into our music just as naturally as jazz did. This is especially true of the music of our leading American composer, Aaron Copland. Copland is an old friend of ours by now, since as you may remember, we had an entire program of his music two years ago, to celebrate his sixtieth birthday, when among other things we played his famous El Salon Mexico—which was his musical souvenir of a Mexican visit. This time we are going to play a delightful short piece by Copland that isn't heard as often as it ought to be: This one is a souvenir of his Cuban visit and is called Danzon Cubano, which doesn't mean "Cuban Dance" but "Cuban Danzon", which is a little different.

A danzon is a special kind of dance, in two clearly separated parts: the first part is always very elegant, restrained, and crisp; it's wonderful to watch the Cubans do it in their dance halls; because whatever social background they may come from, they look like princes and princesses as they dance the danzon, very straight and aristocratic, making clean, tiny movement.

Then, suddenly the dancers make a little pause, while they gently apply their handkerchieves to their moist upper lip very daintily, even the huskiest truck drivers, for all the world like the eighteenth century courtiers; and then, without any signal, as if by magic, they begin to dance part two, which is usually a bit faster and more exciting. But right to the end they never lose that royal bearing and control; and if we can ever go to Havana again, I hope you'll all get a chance to see a Cuban danzon in action. In the meantime, here is Aaron Copland's symphonic version of the Danzon Cubano.

Pretty hot stuff. Now most of the music we have played so far has probably not been very familiar to you; so now we are going to play something that may be a little more familiar—some of the dance music I wrote for West Side Story. A lot of my music does show Latin American influences, but the music of West Side Story is particularly Latin, which is only natural since the story of this show is in great part about Puerto Ricans. And we're going to play you four of the dances from that show, in a special new symphonic orchestration. The first two of these dances are straight out-and-out Latin dance-forms: the mambo and the cha-cha. But the interesting thing to me is to hear how Latin-influenced the other dances are, which are not mambos, or anything. For instance, in the jazz piece called Cool there are hints of bongos and other Latin sounds; and this is a piece that even has a serious fugue in it. And even in the rumble, which is simply ballet music that tells part of the story, you'll hear rhythms that will probably make you think of Cuba and Mexico. Which all goes to prove that the word America means much more than only the United States—that North America, South America, and Central America are, or ought to be, a solid united hemisphere. But let's not get into politics; let's get into the Latin American spirit with the mambo from West Side Story.

END

© 1963, Amberson Holdings LLC.

All rights reserved.