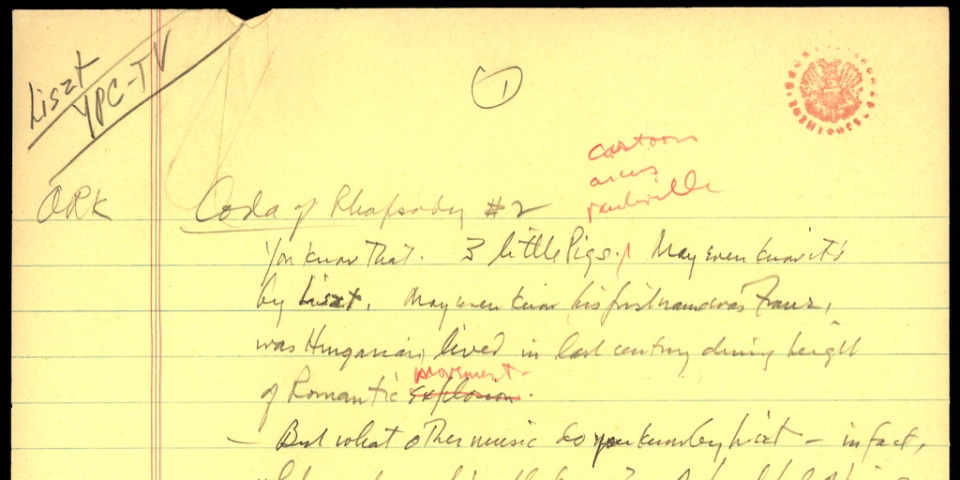

Lectures/Scripts/WritingsTelevision ScriptsYoung People's ConcertsLiszt and the Devil

Young People's Concert

Liszt and the Devil

Written by Leonard Bernstein

Original CBS Television Network Broadcast Date: 13 February 1972

[(A) - (D) - 5 + tympani]

Now there's a terrific hunk of music. And I'll bet very few, if any, of you know what it is. And yet it's by one of the most famous composers of all time, Franz Liszt. And what's more, it's from his greatest piece, the Faust Symphony. Of course, the reason you don't know what it is, is that it's so rarely played. After all, how much of Liszt's music do most people know anyhow?

[Cross to piano]

Really, a handful of pieces, mostly ones you remember from childhood, like this one

[Play]

which you all know is Liebestraum or the famous Eb Major Piano Concerto

[Play]

or some of the more favorite tunes from the Hungarian Rhapsodies like this one,

[Play]

or, of course,

[Play]

which you've all heard in the cartoons and so on, or this one

[Play]

millions more of those. But, as you see they're mostly piano music, which is natural, since Liszt was the greatest pianist of his time, and some say of all time. But actually, he wrote tons of non-piano music — songs, choral works, symphonies, symphonic poems, whatnot.

And most people don't know them because they're simply not performed very much. And this is an interesting question: why? Especially since Liszt was the most celebrated musician of his time about a century ago, and a tremendous influence on other composers, especially on Wagner, and on Debussy even, who are played all the time. So, why not Liszt? Well, partly to answer this question, the New York Philharmonic, under its brilliant new director, Pierre Boulez, is featuring works of Liszt all through this season's programs. And one of my contributions to this survey is what I consider to be Liszt's true masterpiece his Faust Symphony. I think most musicians would agree with me that this Faust Symphony is one of the monumental works of the whole Romantic Movement.

I want you to hear some parts of this extraordinary symphony today, not only because it's such exciting music, but because in a funny way, it may throw some light on this nagging question about Liszt himself —- the double question really of why his works are so neglected, and, secondly, why he is not thought of as belonging exactly up there in the highest musical heavens along with Beethoven and company. And I hope by the end of this program we may have -some clues.

OK — first things first. Before we can know anything about Liszt's Faust Symphony we have to know something about Faust, whoever or whatever that is. Well, for hundreds of years, before Liszt's time, there had been circulating fabulous stories about a certain Dr. Faust, a mysterious old magician who went about Europe doing his various magic acts — you know, things like conjuring up spirits, turning base metal into gold — stuff like that. Now, in those years, when superstitions were running riot, simple folk were ready to believe anything, especially about men of great learning. They were always considered magi, and this mythical Dr. Faust was supposed to be as learned you could get. So, naturally, the legends about this miracle man captured the imagination of the people who automatically assumed that Dr. Faust must have acquired his magical powers by being in league with the devil or Satan or Mephistopheles, or whatever you wanted to call him. In other words, that he must have made a bargain with the devil in which he sold his immortal soul in return for total knowledge and power for an earthly life of guaranteed pleasures. It's a simple deal — trading the vague promise of Paradise for the reality of fun right here on earth. It is a myth that's as old as time, and it still persists to this day. We all make magical bargains all the time. Haven't you ever wanted something so badly that you've said, "Oh, I'd give anything, I'd give my soul if only such and such would happen." Well, that's making bargains — with whom I'm not saying. But that's the essential myth of Faust, which finally arrived at its supreme literary expression in the great poetical dramas by Goethe. That's G-O-E-T-H-E: and please don't say you never heard of him, because then I'll have to explain all about him to you, and we'll never get back to Liszt and his music. Let's just say that Goethe, of course, was the greatest poet of the German language. I'll tell you that much. But Goethe's drama of Faust is one of the monuments of all literature, with its mystical story of Faust's bargain with the devil, his ultimate triumph over the devil, and his redemption through love. Now Goethe spent his whole life writing this masterpiece. He began it as a young man of 20 and kept at it, off and on, until his death in 1832, which brings us smack up to Franz Liszt, because Liszt in that very year of 1832 was himself a young man of 20, and in turn, carried Goethe's Faust with him all through his life; he adored it, it was always by his side along with his Bible. And in some way he seemed to identify with this Faust character; he was possessed by it, almost until finally it burst into musical life in the form of a Faust Symphony. Now here's where things get really interesting because actually Liszt was a sort of Faust — not in the sense of the old phoney magician of the legends but, in the sense of Goethe's Faust, quite a new and different character and a fascinating, complex Faust, a striving, daring, endlessly inquisitive man, who had to know and do end experience everything.

And Liszt was just like that, in his way; he seemed to do everything and he did it all with smashing success. A mere 9-year old boy pianist, he was already knocking them dead in his native Hungary, and one year later, he was doing the same in Vienna, where he was such a smash that he was publicly kissed by Beethoven. And before he knew it he was the rage of London and Paris and the darling of the whole musical world. When he played the piano, grown men wept and women fainted. It was like that. And people began to say, half-seriously, that there was something diabolical there, something spooky, some bond he must have made with the devil. Otherwise, how to explain these magical Faustian powers of his? And what's more, he seemed to have control over his own destiny; for instance, at the very peak of his fame, still a young man, he decided he had had it with the piano, and so he just stepped playing recitals and devoted himself to composing and conducting - and to his ever-continuing love life; oh., there was lots of that. Very successful indeed.

He even had children, although he never got married; and to top it all off, and this is really incredible, he even received minor holy orders in Rome, becoming an Abbe in his later years. In other words: he had it all. On the one hand he was a good, kind, religious man famous for his charitable acts and for his generosity to other composers, whose works he was always championing. And he gave lessons constantly — if he liked a pupil he gave them free. He was that kind of man. On the other hand, he was also a social lion, dynamic, witty, sexy, famous and endlessly gifted. Well, what is this? You can't have everything, and yet he seemed to, but there's got to be a catch somewhere. Well, let's see if we can find it in his music — in this Faust Symphony itself.

This symphony has 3 movements, which don't so much tell the story of Faust as paint 3 portraits of Goethe's main characters; in fact, Liszt called it a "Faust Symphony in 3 character pictures" after Goethe.

The first movement or picture is devoted to Faust himself, the scholar and teacher, who has been sitting for years at his desk studying everything there is to be studied, searching for the real meaning of life and not finding it, and thinking that there must be another kind of knowledge, some magic secret not to be found in books, a way to keep life exciting and meaningful, and full of passion and youth, achievement, love beauty, and glory, Doesn't that sound a little bit like Liszt himself? (Hint).

[Cross to PNO]

Alright, now listen to the way Liszt begins to describe this brooding, old philosopher Faust:

[PNO]

Do you hear the despair and doubt in that opening theme? — and do you know why? It has no key. You see it's all the 12 notes of the chromatic scale. I hope you know what that means.

[PLAY]

— all those 12 notes which are divided up into 4 groups of 3 notes each

[PLAY]

— 12 different notes.

In other words, Liszt, that daring, brash romantic pioneer, had written the first really atonal music a century before atonal music became the thing to write. Now, listen again to this history making 12 tone row, and see if you can hear the sinking despair and doubt in it as it travels down. You see and now this doubt theme raises its head in yearning

[PLAY; V.C.]

yearning for love and magically turning into Faust's second theme:

[PNO]

[CROSS TO PODIUM]

And so you see right in this introduction, Liszt has given us 2 Faust-themes in one, which combine perfectly into a portrait of this aging, book-weary scholar yearning for life, for love.

[ORCH (1st 7 bars)]

Do you understand? But suddenly Faust leaps up in a rage of impatience and frustrations, he's had it, and we hear that doubt-theme now slashing through in the brass, no longer brooding, but now fierce and desperate.

[ORCH (B) - (C)]

That's Liszt at his most brilliant, dramatic, wild, sparks flying everywhere. And so now Faust is- ready for action: he has resolved to do something about his life, even if it means teaming up with the devil. And the rest of this movement is all about how Faust's life could be, once he took the plunge; and it's all based on those two themes, plus three more Faust themes, which are like three wish-dreams. He has one showing youthful passion, what he's yearning for, and the next a dream of love, a pure ideal love, and finally the theme of Faust the hero, in full glory. Here's the first: of the 3 themes of passion: That's passion:

[ORCH (D) to (E) dbt.]

And in direct contrast to that comes the theme of ideal love:

[ORCH (K) + 2 - (L) + 4]

It's a beauty, isn't it? But there's an extra magic involved in that. Because if you were listening carefully, you must have heard that the music is simply a transformation of that old yearning theme we heard earlier. Do you remember it?

[OBOE & CLARINETS 1st Ent. Ubt. to 4th bar [2 bars]]

You remember that. But Liszt, the magician, takes that yearning tune with its uncertain harmonies and faltering rhythm and transforms it, by some kind of musical hocus-pocus, into this secure, sweet, shining melody

[ORCH L for 2 bars]

It's like pulling a rabbit out of a hat. In other words, Liszt has, by magic, made Faust's yearning come true before our very ears. And so onwards to the last of the Faust-themes which is the wish-dream of the glorious hero in full triumph.

[ORCH (0) - 1 to dbt. 14th bar]

Heroic. And there you have all the elements that are needed to make up a portrait of Faust — the doubting, the yearning, the passionate dreams of love and glory. But these themes are only elements; they make up a sketch of Faust but not a portrait. Liszt paints the total picture by transforming those elements, those themes, in the same way that we just heard the yearning theme transformed into the love theme. And transforming means also combining one theme with another so that we see different aspects of them in different relationships. For instance, later in the movement there's a moment when that yearning love-theme, now grown very heavy and angry [SING] is set up by Liszt against the heroic theme, which has gotten pretty angry:

[ORCH (P) 9 bars - dbt.]

Now you see that's a new wrinkle in old Faust's forehead.

It's really becoming a portrait now not just a sketch. We are just beginning to know Faust as a man and not just as a story-book name — a man with an insatiable quest for the meaning of life.

And now, I think you're ready to hear a part of this movement, without interruption, so that you can experience some of these transformations, even for a short while, and through them get to know and understand this fabulous Faust figure, as though he were someone you'd known all your life.

[ORCH PLAYS A SECTION PART III]

Where were we? Oh yes, we left Faust sitting in his study, sunk in his Lisztian-funk, and quite resolved to renounce God, and to use all the arts of black magic to call up the devil. The only one he can think of who can make his wish-dreams come true even if it means paying for it with his soul. As you know, this does happen. Mephistopheles does appear in all his cool, hip, swaggering irony and cynicism and the contract is made and sealed in blood. Mephisto is to be Faust's servant during his lifetime providing him with everything he has dreamed of — youth, love, power, the works. But when it's all over the roles will be reversed, and Faust must become the devil's slave, forever. Such are the wages of sin, as it turns out, there is a glorious happy ending. But for the moment the glory is on the other hoof; and the devil is busy doing his job providing Faust with the perfect girl, innocent, pure, ideally beautiful. And through the devil's magical powers, Faust will have this girl, win her love and ruin her life. This girl is named Margaret, or Gretchen, as she is familiarly called and Liszt devotes his whole second movement to her portrait. It's one of Liszt's loveliest pieces, tender, fresh, and utterly romantic. But since Gretchen en is after all a simple, devout girl, without any of the sophisticated hang-ups of Faust, her music is equally simple; there just aren't that many aspects of her character to portray. And so Gretchen has really only one important theme — a tender, flowing melody of unforgettable beauty.

[ORCH A + 6]

Isn't that a beauty? That's Gretchen in love, poor little thing, and let's be kind to her and leave her in her blissful state, Because it's time for the dazzling entrance of you-know-who, the Devil himself, whom Liszt chose to portray in his extraordinary in his extraordinary third and final movement. Mephistopheles appears in flashes of fire and brimstone, smirking, sarcastic, tricky — thoroughly evil, but a heck of a lot more fun than either Faust or Gretchen were. Now mind you, I'm not putting them down or trying to make the devil out to be anything particularly glamorous or attractive. The point I am trying to make is that in some curious way, and judging only by the music, Liszt liked that devil. It brought out the best in him - - the most imagination, the most invention, and orchestral brilliance. And perhaps the most remarkable thing about this Mephistopheles Movement is that there isn't one single new theme in it [CROSS TO PIANO] unless you want to count this little devilish figure which goes [PNO] which is hardly enough to be called a theme. So actually the whole movement is nothing but one big transformation of all thoseFaust themes. We've already heard the first movement — all of them mocked, and changed and distorted into devil music. You remember the yearning theme for instance [PLAY]. Well, here it is transformed into diabolical mischief:

[ORCH B to G dbt.]

And you remember that old 12-tone doubting theme? [PLAY] Well, here it is again satanized and parodied; and listen for the devilish sneering in the woodwinds,

[ORCH E + 2 Ubt - 4 bars]

Heh-heh. Now that really tells us the story: there is Faust, plain as day, in the clutches of the devil. Then, at one moment, there is a sudden hush, and the pure music of Gretchen's theme reappears [PNO] as if trying to separate Faust from The Fiend, but it's a brief try: [MOVE TO PODIUM], because a second later, back comes the hollow, mocking laughter of the Prince of Hell.

[ORCH ubt to HH + 6 for 4 bars]

It seems hopeless, but of course, in the end, as in the end of Goethe's Faust, love does triumph over the devil. Gretchen's soul is saved because of her sincere devotion to God. Even Faust is finally borne aloft to Heaven by singing angels, redeemed by the pure love of a pure woman and, by the powers of heaven which, after all, are greater and more merciful than those of the devil. And yet Liszt didn't spend too much time or energy on this happy ending; it occurs rather abruptly, and is surprisingly short. What happens is this: just before the end things peter out a little bit, all that devilish madness calms down, the Gretchen Theme sneaks in, spreading light and compassion, and there are a dozen bars or so of majestic build-up of Faust's glory-music, and the symphony is ever just like that. It's not your average redemption ending by any means. Especially for a big philosophical symphony like this. And don't think Liszt didn't know it. Because a few years after he had finished it, he added a whole new longer ending, longer and more religious, with an organ and a chorus, and a solo tenor singing Goethe's final mystical verses. But that was obviously an afterthought. What Liszt really cared about in this finale was that old devil. And come to think of it, he did write an unnatural amount of devil-music. Because besides this Faust Symphony, he wrote a Dante Symphony, which also deals with hell, inferno, he wrote a piece called Totentanz, a Dance of Death, a piece called Malediction, which means the Curse, he wrote 4 different Mephisto Waltzes, and even a Mephisto Polka! He was Mephisto-mad, Which brings us back to the question we asked at the beginning; how did Liszt come to have it all — fame, glory, women, and all the rest? Was he a musician or maybe a magician? Was that priestly robe of his perhaps a Sorcerer's robe? Many people have thought so; even people of his own time who knew him had the impression of a Wizard, a Merlin, rather than a man of the church. Was he perhaps in some way a Faust? Could there have been, so to speak, of course, some contact with infernal powers? And, if so, what was the bargain? Well, we certainly can't prove whether Liszt's soul went upwards or downwards after he died. But could it just be that he was doomed to go down in history to this very day, as a composer of questionable greatness? Oh, yes, Liszt, people say — a fascinating type, a great virtuoso, terrific, all that. But he's never spoken of in the same breath with Mozart and Bach and Wagner. He's just — Franz Liszt, the old magician.

And yet, magically enough, here is that Faust Symphony, and acknowledged masterpiece. Some have even called it the masterpiece of the whole Romantic movement. Could it be that Liszt, like Faust, really did finally triumph over the devil? Well, let's listen to this final movement, and then we can all make up our minds. So, here comes the devil now, in a puff of smoke and a flash of lightning.

[PLAY]

END

© 1972, Amberson Holdings LLC.

All rights reserved.