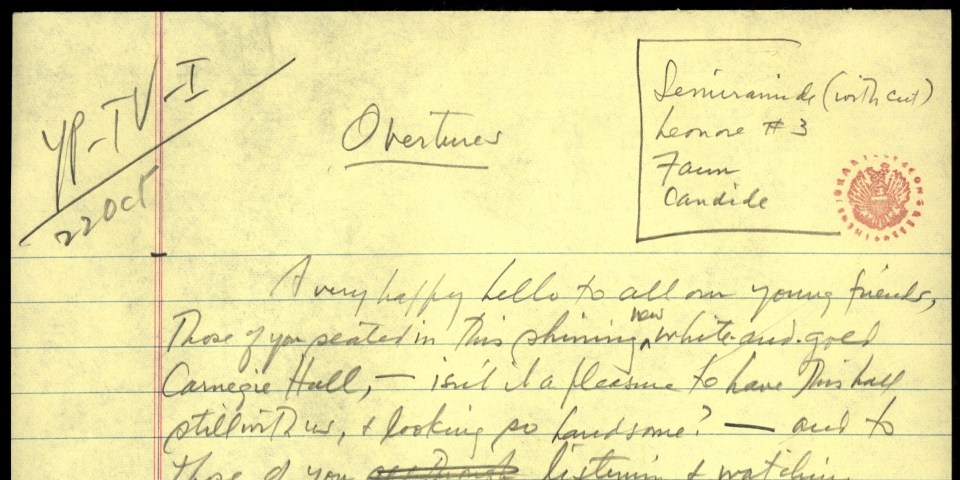

Lectures/Scripts/WritingsTelevision ScriptsYoung People's ConcertsOvertures and Preludes

Young People's Concert

Overtures and Preludes

Written by Leonard Bernstein

Original CBS Television Network Broadcast Date: 8 January 1961

LEONARD BERNSTEIN:

A very happy hello to all our young friends, first to those of you seated in this shining new white-and gold Carnegie Hall, — isn't it a pleasure to have this hall still with us, especially looking so handsome? — and to those of you listening and watching everywhere in America and Canada. *[As you may know we have recently made a long seven-week tour of this continent — even going off the continent to visit our newest state, Hawaii, and, in the other direction, the city of Berlin, Germany. Quite a long and exciting (and tiring) trip, as you can imagine; but one of the most pleasant parts of it was the chance we had to meet so many of you in person at our concerts, and to find out personally how much you like music and our Young People's Concerts.

*[In fact, we even gave two Young People's Concerts during the tour--one in Chicago and one in Vancouver, Canada — and they were marvelous fun for us to do! You see, we had never before given this kind of concert anywhere but here in New York; so that was a new experience. The subject of those two concerts was Overtures: and those of you who were there in Chicago and Vancouver seemed to have such a good time that we've decided to do it again here in Carnegie Hall and on television, so that you can all share in.] For our first program today, our subject ... But why a program of just Overtures? Well, I'll tell you. When I was a boy, first discovering music, the biggest kicks I got always seemed to come from Overtures. It was an overture period, in those days — I don't know why. Everybody seemed to be playing Overtures all the time. But there was something so exciting about hearing a Rossini overture, like "The Barber of Seville" or "William Tell" come swinging over the radio, (or "Poet and Peasant" or "Zampa") — that I used to wait breathlessly for each new program, in hopes that an overture would be played.

You see, I heard most of my music at an early age over the radio, because I [...] children's concerts in Boston, where I lived. Maybe, too, it was because at that early age a whole long symphony in four movements would have been too much for me to absorb, as maybe it is for all of you. But an overture seemed just right, just the right length; and besides, it had such excitement. So today I'm going to try and recapture some of that excitement for myself, and I hope for you too, by playing a whole program of nothing but overtures. I'm sure that part of the excitement about an overture comes from the fact that it is part of the theatre — it combines the wonders of music with the thrill of the theatre. After all, what is an overture? It's a beginning, an opening piece, usually written to be played in the musical theatre before the curtain goes up.

I'm sure you all know the excitement of that moment before the curtain goes up — that breathless hush in the audience, that sense of expecting, of suspense, of "what's going to happen now?" It's the same with or without music; even in the movie theatre. I'm sure you all know the excitement you feel when the lights go out, and the Mickey Mouse or whatever it is flashes on the screen. Everybody claps and says, "Oh Boy! now it's beginning!" It's the same in the musical theatre, or in the opera; the lights go out, there's that shivery moment of silence in the audience, the conductor appears out of nowhere down in the orchestra pit, and there's the overture — that wonderful piece that gets you ready, that sets the moods, that starts your musical blood going, That's the kind of overture we're going to play first — the overture to the opera "Semiramide" by Rossini.

Rossini is the same Italian composer who wrote "The William Tell Overture" which I'm sure you all know as that galloping thing they always play for Westerns and cowboys and "The Lone Ranger".

(SING)

Rossini also wrote "The Barber of Seville" and many others. But this opera "Semiramide" — that's a long hard word, isn't it? — and it doesn't mean a semi-ramide, or half a ramide, whatever that may be; Semiramide is the name of an old Babylonian queen; and I won't bother you with the story of the opera at all. Besides, it's almost never sung anymore. But the overture to this opera is played all the time, because it's one of the greatest examples of an exciting overture that gets your blood going, and puts you in the mood for the rest of the performance.

It has a really breathless beginning, which also may remind you of galloping, as a matter of fact. It goes like this:

(EXAMPLE: ORCHESTRA INTRODUCTION) (:30)

Then comes a long slow part with a very famous tune played by the French horns. Like this:

(EXAMPLE: ORCHESTRA - 8 bars German tune) (:30)

and then begins the main fast part, which is wildly exciting. Wait till you hear those violins skittering around, like this.

(EXAMPLES: ORCHESTRA - ALLEGRO) (:12)

and then, best of all, Come those long build-ups of sound that Rossini is so famous for — they're called crescendos which means gradually getting louder and Louder and LOUDER. Like this:

(EXAMPLES: ORCHESTRA- CRESCENDO) (:18)

(APPLAUSE)

That's what makes a Rossini overture such fun, such excitement. I hope you all find it as much fun as I did when I was your age. Here goes.

ROSSINI - OVERTURE TO "SEMIRAMIDE" (11:40) (with possible out...(10:00)

Now we come to a much more serious overture, in fact, one of the great masterpieces of all music — the Third Leonore Overture by Beethoven. Now that's a peculiar name — Third Leonore Overture. Why the Third? And Beethoven never even wrote an opera called Leonore. What is this great mystery? Well, it's this way. Beethoven did write an opera called "Fidelio" and he also wrote an overture to it, known as the overture to "Fidelio." We're not going to play that. But he also wrote three other overtures to it — you see, Beethoven was never satisfied; he was always trying out something new that might be better. Great artists are that way, they're very hard to satisfy, especially by their own work; and Beethoven was one of the greatest, and therefore one of the hardest to satisfy, and the one who most of all kept changing and improving all the time, all through his life to make his music better. So he wrote those three other overtures, named Leonore, which at one point had been the name of this opera, before it was called "Fidelio"; and of those three, naturally the third is the greatest one.

In fact, it's such a marvelous piece that even today it is always played when "Fidelio" is given at the opera house, only not before the opera, but during it, that is, just before the last act. It's a story of a man is unjustly put in prison, and is going to be killed, but is saved in the nick of time by his faithful wife, Leonore, who gets into the prison disguised as a boy named Fidelio. Clear? I hope so. I can hardly follow it myself — Anyway, there's a great moment in the opera when the hero is saved, and you hear the trumpets way offstage announcing the arrival of the governor, which means that the wicked jailer is not going to be able to do his dirty work after all. This trumpet moment is kept by Beethoven in the overture; and I think you'll find it an unforgettable moment when you suddenly hear that trumpet-call coming at you from way off somewhere behind those walls, in the depths of Carnegie Hall. Here is Beethoven's Third Leonore Overture,

BEETHOVEN - LEONORE NO. 3 (13:20)

APPLAUSE

Well, so far we've had an overture to an opera, and an overture to the last act of an opera. Now we're going to hear something even more peculiar: an overture to no opera at all. Just an overture, period. There are such things, you know, *[like "The Roman Carnival Overture" by Berlioz, or the American Festival Overture by William Schumann, or even Beethoven's overture, Coriolanus.] which are also meant to be opening pieces, only they open symphony concerts instead of operas. But they're still overtures. See? Very simple. Now the one we're going to play has even another peculiar twist: it's not even called an overture, it's called a prelude. Now don't let this throw you. A prelude is also an opening piece, a thing to be played first, before the main event— like a preliminary boxing-match at a prize fight.

So why is it different from an overture: Well, for one thing, a prelude is usually shorter than an overture; and it usually doesn't have different parts - slow parts and faster parts - like the ones we've been hearing. A prelude is all in one, all the same tempo, either slow or fast or middlinq. For instance, the prelude to the opera "Carmen" is fast (SING) and the prelude to the opera "La Traviata" is slow, (SING) and the prelude to the opera "Die Meistersinger" by Wagner is middling. (SING) Well, the one we're going to hear now is a slow one — a real beauty, by the great French composer, Debussy. It's called "The Afternoon of a Faun," and if anyone asks you why this one is a prelude, there's just no answer. Debussy called it a Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun, borrowing this title whole from a famous French poem of that name by Mallarme, (another name you can forget).

Of course, there is no opera attached to this prelude at all; it's just a piece to be played at the beginning of a program, although there's no law that says you can't play it in the middle of a program, or at the end, either for that matter. It is a lazy, hazy sort of piece, full of warm, stretchy sort of feelings, sometimes very delicate, and sometimes quite passionate and full of goose-bumps. It's a marvel, this piece; you can almost see, and smell, and feel a delicious summer afternoon, as you listen to it. It's like looking at a painting, only with looking with your ears instead of your eyes. Debussy's Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun.

DEBUSSY - PRELUDE TO THE AFTERNOON OF A FAUN (10:45)

(APPLAUSE)

Well, that's a lot of overtures we've been hearing. All kinds, all shapes and forms: an Italian one, a German one and a French one. But there's one kind we haven't heard yet, and that's an overture to an American Broadway musical comedy. So, as a sort of dessert, we're going to end this program with a very short overture, by, of all people, me — the overture to my operetta, or musical, or whatever you want to call it — named Candide. I wrote this show about four years ago, and it didn't do very well. It ran only about two months on Broadway, and then closed. Very sad. Especially sad, because the show was supposed to be very funny, not sad at all. Well, the show is temporarily over, but the overture lingers on, I hope; and I also hope it will give you an idea of some of the fun and frolic that was in that show. Here is the overture to Candide.

BERNSTEIN - OVERTURE TO CANDIDE (4:15)

* CUT

END

© 1961, Amberson Holdings LLC.

All rights reserved.