Lectures/Scripts/WritingsTelevision ScriptsYoung People's ConcertsThe Road to Paris

Young People's Concert

The Road to Paris

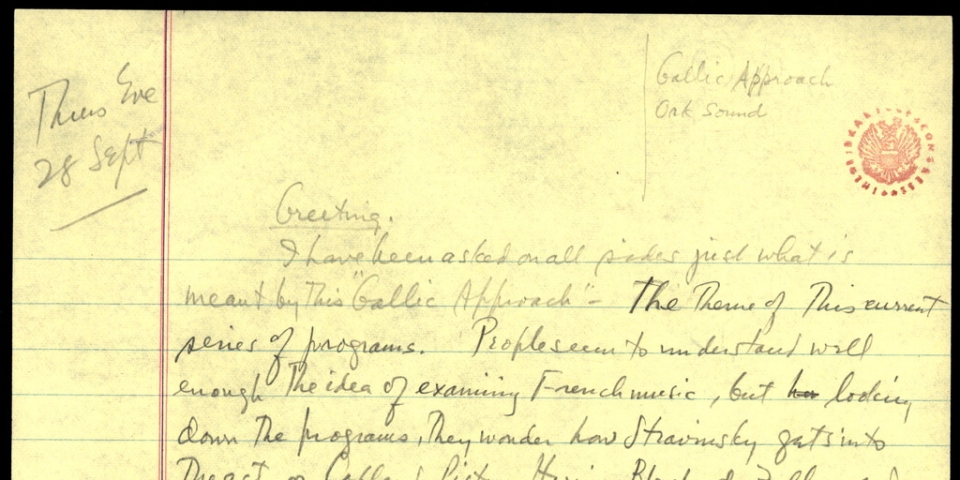

Written by Leonard Bernstein

Original CBS Television Network Broadcast Date: 18 January 1962

LEONARD BERNSTEIN:

Greetings. I'll bet some of you, or maybe even a lot of you, are mystified by the title of today's program— "The Road to Paris." What can that be about? A Bob Hope movie? Or maybe the history of the French Revolution? Well it isn't—strangely enough, as you probably guessed, it's about music—music written by three composers, one from America, one from Switzerland and one from Spain. Now all three of those men had strong musical languages of their own, based on their own national traditions—Spanish or American—and yet they all set out for Paris as young men in order to polish and perfect that language sort of to acquire a French accent, so to speak, because they considered Paris to be the center of the musical world.

But why Paris? Why not Vienna, or Rome, or Moscow, which were all also great musical centers? No, it had to be Paris, especially around 1900, Paris, which suddenly almost exactly at the beginning of our century, had become the exciting place where new things were happening in music, where you found fresh air, and great new names, and a fever of creative energy. Musicians from all over the world were drawn to Paris as if to a magnet, especially by the fascinating new personality of Debussy.

I hope you remember that great name, from our last program a few weeks ago, when we played his masterpiece about the sea, called La Mer, and learned a few things, I hope, about Impressionism. You remember? Of course you do.

Well, Debussy—and Ravel, and the group of new composers that were growing up around them— had started writing such original, fresh, and tasty music that young composers from everywhere felt that Paris was now going to be the new musical center of the world. The great line of German and Austrian music from Bach all the way to the Strauss seemed somehow complete in 1900, finished. And the new French composers who then began attracting such attention in the early 1900's seemed like a promise of new hope, new sounds, a new way of writing and thinking about music. And so the magnet began to work, and suddenly everybody had to go to Paris. Take George Gershwin, for instance, the most popular and famous composer America has ever produced.

He was always visiting Paris— not necessarily to study, but because he liked it, because it attracted him like a magnet. And his music shows it, even in the title of the piece we're about to play—An American in Paris. This title tells us that the music is supposed to represent an American's impressions of the French city, the taxi-horns, the wine, the fun, the cafes, the homesickness and all the rest of it; but the title also tells us a much more important thing, too—it tells us about an American composer named Gershwin under the musical influence of Paris. After all, Gershwin was a Brooklyn boy as you know, brought up in pop-song publishing houses and Broadway shows, and his musical language was jazz; his tunes, rhythms and forms were all rooted in popular music; and so it was those roots that grew into the hearty perennial plants that we know as The Rhapsody in Blue, The Concerto in F, the opera Porgy and Bess, and this American in Paris we're going to hear.

All serious, big compositions, and all with their roots in jazz. But it was the Paris sunshine that helped those roots to grow. For instance, do you remember last time we talked about the whole-tone scale— that strange, impressionistic scale that Debussy used so well sounds like this.

Here it is, in the middle of a piece full of blues and Charlestons and swingin' tunes, but it's here:

You remember that vague, unfinished sounding scale? Of course you that those peculiar noises in the back are supposed to be?

French taxi-horns. But they're not just noises— they're notes of the whole-tone scale. Imagine. The only difference is that Debussy used those notes to paint dreamy sailboats, and waves, and mists, while Gershwin used them for taxi-cab horns. Or again do you remember that wonderful, hard word bitonality that we also found in Debussy's music last time? If you do, then you know that it means composing in two different keys at the same time, remember?

Well, bitonality also turns up in Gershwin. For instance, he takes one of those swingin' tunes of his that goes like this;

and later on in the piece he brings back that tune in a sort of misty, impressionistic disguise, like this:

Now that's genuine imported French impressionism. How does he get that French sound? First of all, he gets it by using our friend bitonality.

You see, each of those chords you just heard is really two different chords at once, in two different keys. The higher instruments are playing one set of chords in one key:

And the lower ones are playing a whole different set of chords, in another key:

And together they make the bitonal sound, like this:

you hear how misty that is, it's even a little woozy— but I think that in this moment Gershwin is trying to show his American visitor to Paris a bit tipsy with too much good French wine, and that explains why it's so misty and woozy.

In fact he adds to it an even mistier color of the celesta:

and then the plucked strings:

and behind it all he adds the soft hiss of the cymbal, like a ringing in your ears.

and then he puts all those sounds together to make this lovely, unreal, tipsy, woozy, impressionistic sound that he learned on the road to Paris.

Now, all that is just one little example of the French influence on Gershwin, but perhaps this one will help you hear this piece in a new way, if you remember that Gershwin not only wrote An American in Paris, but as a composer, he was an American in Paris. And here is the result of it.

Now we turn to a very different kind of composer indeed—older and more serious that Gershwin—Ernest Bloch. His was a mixed-up sort of background; he came originally from Switzerland, where he first studied, then he went and studied in Belgium and Germany; and he finally wound up living in America. So you might say he had many different kinds of national roots; but just to make it more complicated, his strongest roots of all were not so much national as racial, and those were his Hebrew roots. Bloch felt his Jewishness very strongly— so strongly, in fact, that many people believe that his only truly great works are those that grew out of those Hebrew roots— works like his symphony Israel, and his Sacred Friday Night Service, his 3 Jewish Poems for Orchestra, and, greatest of all, his rhapsody for cello and orchestra, Schelomo, which we are going to hear next.

But even with those strong Hebraic feelings of his, Bloch also walked this road to Paris in the early 1900's, and we can hear the same kind of French influence in Schelomo that we heard in An American in Paris. For example, Bloch uses the same kinds of blurry chords we heard in Gershwin, which again make an impressionistic effect, especially when played by that celesta, plus harps, flutes and soft shimmering strings, like this:

You see, even the orchestration is again impressionistic and French. Now listen to how those same misty sounds combine with the Oriental flavor of this Hebrew melody:

Very Oriental indeed, but very French at the same time. We can even find our well-known bitonality over and over again in this piece of Bloch, as in this spot where the basses are playing another Oriental phrase in one key—

while over it the trumpet and woodwinds are playing a whole other theme in a whole other key:

Now together, the two keys and the two themes make this wonderful, juicy, rich sound—

You see how splendid that sounds? How bitonality can sound? And splendid is the right sound for Schelomo, since the whole piece is built about the idea of great Biblical court of King Solomon--Schelomo is the original Hebrew word for Solomon; and splendor is certainly one thing we always think of in connection with King Solomon; and this splendor is made even more splendid by the kind of orchestration Bloch uses-orchestration that reminds us very much of Ravel—do you remember the glamorous sound of Ravel's Daphnis and Chloe that we heard on our last program? Well, here is something like that dazzling sound again, a French sound, remember—which comes at one of the big climaxes of the piece, where it is like an explosion that gives off sparks and rays and lighting flashes, by using trills, slides and swooping scales:

So, you see, Bloch was Swiss, and Bloch was Jewish, and Bloch was American; but without this Paris influence his music simply wouldn't be what it is. Now we shall listen to Schelomo; and we are very proud to have one of the world's very greatest cellists to play this marvelous work with us, Miss Zara Nelsova.

One more word before we play; you should know that the name Schelomo, or Solomon, means peace in Hebrew— related to the famous Hebrew word Scholom; I would like very much—in fact, with all my strength, and I hope with all of yours too—to dedicate this performance to the coming of peace to all the peoples of our world.

Our last composer of the program is the brilliant Spanish master, Manuel de Falla— and his roots are so Spanish you can see them above ground, like the roots of a great oak. This Spanish-gypsy kind of music is, as you know, sharp and clean and rhythmic that you'd never expect it to get mixed up with those misty perfumes of French impressionism, but it does. Even in these dances from Falla's ballet "The Three-Cornered Hat," we can still find those rich blurry harmonies that remind us of Debussy, like this:

And we even find moments of bitonality, too, like this one, where the strings are playing in one key, E major:

While against them the horns and trumpets are playing a theme in a whole other key, F Major:

And together, the two keys make a typical French excitement, like this:

You see what I mean? And as for the orchestration, it is all one big tribute to Ravel and Debussy, with harps and celesta, and trills and scales and runs and glamorous percussion, as you will hear in a moment.I trust that you are no longer mystified by the title, "The Road To, etc." We have seen that in the first third or so of our century the road to Paris was a heavily traveled one by composers of all nations and races—and not only composers with Spanish or Hebrew or American roots, but many others like Villa-Lobos from Brazil, Chavez from Mexico, Prokofieff and Stravinsky from Russia, Malipiero from Italy, and so on and on. They all went to Paris because its French spirit has been very contagious in our century, and thank goodness it has; because it's greatly enriched our whole musical life.

And now here are two dances from Falla's famous comic ballet. The Three Cornered Hat; first comes the Millers Dance, which is a kind of typical Spanish folk tune called a Farruca, and then comes the final dance which is a Jota.

END

© 1962, Amberson Holdings LLC.

All rights reserved.