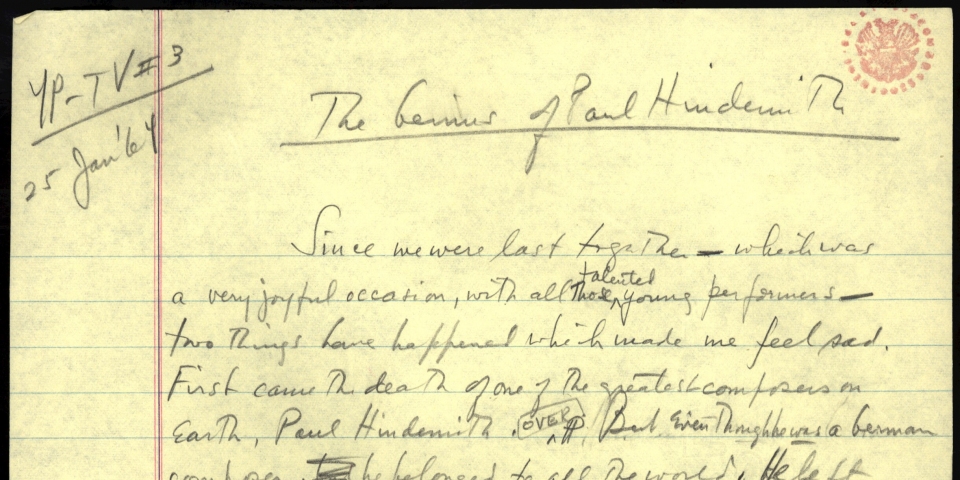

Lectures/Scripts/WritingsTelevision ScriptsYoung People's ConcertsThe Genius of Paul Hindemith

Young People's Concert

The Genius of Paul Hindemith

Written by Leonard Bernstein

Original CBS Television Network Broadcast Date: 23 February 1964

LEONARD BERNSTEIN:

Since our last program — which was a very joyful occasion, if you'll recall, with all those talented young performers — since then a sad thing has happened: the sudden death of one of the greatest composers on earth, Paul Hindemith. Hindemith was particularly beloved by all of us here at the Philharmonic and only last season conducted this orchestra for two weeks on this very stage.

Paul Hindemith was a true master in the great German tradition, a master of melody, of harmony and counterpoint and rhythm and form and orchestration and everything that has to do with music, and he wrote beautiful music. He was a worthy successor to the long line of great German composers that included Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, and Wagner; and in the minds of many people he was the last of that traditional line.

Of course, people didn't always think that way. When Hindemith's music was first beginning to be heard in this country, there were outraged cries of "ugly, shocking, dissonant, Bolshevik, unmelodic, heavy, brutal, bitter, atonal" — especially atonal. That word was very loosely used in the old days, to mean almost anything uncomplimentary about modern music, but Hindemith was never atonal; all his music depends in one way or another on a sense of key, or what is called tonality. Now before we do anything else, let's try to clear up once and for all what the word atonal means: it means using the 12 different notes of the chromatic scale

[PLAY]

in such a way that no one note ever seems more important than another — in other words, no idea of a key, or a home base, is ever established, as it is in the diatonic 7-note scale.

[PLAY A SCALE]

Composers who write in the non-tonal way, following the system invented by Arnold Schoenberg, usually begin their pieces by what's called a tone-row — that is, putting all the 12 tones in a certain order, like a scrambled scale

[PLAY]

and then basing the whole piece on that 12-tone row.

Hindemith was the last great German composer to resist the temptations of Schoenberg's 12-tone method, even at the risk of being called old-fashioned. But 30 years ago, when we were just beginning to know his music, he seemed anything but old-fashioned.

I remember very well my first discovery of Hindemith — some piano pieces by him called "Three Exercise Pieces;" and I was fascinated by what seemed to me their daring and dissonance and defiance. They were fiendish! The first one starts like this:

[PLAY]

And so I immediately decided that Hindemith was a revolutionary, a Bolshevik. But I got a big kick out of it; because like any other young man I was attracted by anything defiant and shocking.

*[I used to go around playing these pieces at parties at the drop of a hat, and I'd love to watch the amazed faces around me. So, I automatically stuck a label for Hindemith — an angry young man, a composer who was out to shock everyone.]* But as I grew older I began to discover that that same etude-piece I had been playing at parties wasn't basically much different in its nature from, let's say, a 2-part Invention by Bach. That is, it's a piece written to develop strong fingers, and provide some interesting music at the same time, so that the pianist doesn't get bored with practicing. Look, here' s a bit from a Bach invention;

[PLAY]

And here's a bit of the Hindemith one:

[PLAY]

What's the real difference? Only one of language; the intention is the same — not to shock, but to instruct. Not Bolshevik, but traditional. Only Hindemith's notes are much more advanced, as they naturally would be, being written over 200 years later. And once we hear it this way — as a continuation of what Bach started — Hindemith's music suddenly begins to sound much more "normal." There's nothing shocking about it;

[PLAY AGAIN]

You see, I was beginning to find out that Hindemith really did belong with all the great German masters that had preceded him. His 2nd Piano Sonata, in spite of its peculiar notes — its "modern" notes, let's say — was really only a new kind of Sonata by old Haydn. It starts like this:

[PLAY (MORE)]

Well, at first hearing, that may seem odd. But listen again, carefully. The left hand is doing just what Mozart and Haydn always did — what's called an "Alberti Bass" —

[PLAY]

And the right hand is playing a lovely, simple tune,

[PLAY]

So what makes it peculiar? What are those modern notes? They are simply notes that are freer, that make new combinations, that enlarge and enrich the musical language. I could easily rewrite that bit of music, using the old kind of notes, and it would come out like a real old-fashioned German tune:

[PLAY]

You see, it's only Haydn in a new suit. And those "modern" notes are only what are called cross-relations. That's not as hard as it sounds: let me show you. This piece is in the key of G; so, in the old-fashioned way, you'd expect the tune to be made out of the notes of the G-major scale:

[PLAY]

Now the 6th note of that scale is E natural, which occurs in the melody;

[PLAY]

but in the preceding bar, in the accompaniment, we have just heard Eb;

[PLAY]

So these two conflicting notes, Eb and E natural, coming so close together, side by side, are called a cross-relation — simple. And all it does is to make the language of music richer, like adding new words to the vocabulary. But the music is still basically good old German lyricism, not at all shocking or ugly. In fact, it's very pretty — only with a new, fresh kind of prettiness. Listen to it again.

[PLAY (but shorter)]

Whatever were people talking about in those old days when they spoke about Hindemith's music being ugly! I remember a lot of heated arguments when we first heard his Third String Quartet which people called viciously dissonant, wild and unpretty. And yet this Quartet contains one of the prettiest, most tender movements in all 20th Century chamber music. It begins like this.

HINDEMITH: QUARTET NO, 3, OPUS 22 (Approx. :30)

The only thing that makes that music at all modern is the 20th century idea of bitonality — you remember, we've talked often about that: music written in two different keys at once, Here- the accompaniment starts very simply in A major.

[PLAY]

and the melody comes in C major.

[PLAY]

And together they sound like this.

[PLAY]

A new, modern sound; but you sure can't say it's not pretty, or dis-sonant, or Bolshevik.

It's hard to believe these days that those outraged words were ever used about Hindemith's music. Another word that was fashionable to use about certain Hindemith pieces was "bitter" — the music was said to reflect the bitterness of the period after World War I.

In fact as recently as the day after Hindemith died, one music critic in his obituary of Hindemith, mentioned this bitterness and to prove it he picked, exactly wrongly, one of the most cheerful and heartwarming pieces Hindemith ever wrote: Kleine Kammermusik or "The Little Chamber Music" for 5 wind instruments. I'd like you to hear the first movement of it and see if you think it's bitter.

HINDEMITH: "KLEINE KAMMERMUSIK" (1ST MOVEMENT) (WOODWIND QUINTET) (Approx. 3:00)

Is that bitter music? It's the exact opposite: gay, light, and full of fun. That was one of Hindemith's main qualities — the joy he put into music. He was a fun-loving man, for whom music was everything. He was my idea of the total musician; he played music, wrote it, taught it, breathed it. He played jazz in cafes; he was concertmaster of an orchestra; he played viola in a string quartet, he wrote books about music; but mainly he wrote music, every kind of music —big, little, serious, light, noble and jazzy, hard and easy, music for professionals, for amateurs, and for children. He was a modern composer; but he was certainly never what we call an Angry Young Man. He had too much love in him for that. He loved all the German music that he was born into — Bach, Mozart, Bruckner; and he just continued it, making his own additions and changes.

And the changes he made caused him to develop a style all of his own; there's a certain Hindemith sound that you can't miss, or mistake for anyone else's. No one could have written that music you just heard but Paul Hindemith — that tune and those harmonies.

[PLAY]

And when a musician says that somebody's music sounds "Hindemithian", we know exactly what he means; it immediately makes us hear a certain kind of sound in our minds.

Now we're going to spend the rest of this program playing Hindemith's most famous masterpiece, his beautiful symphony, Mathis der Maler, which is the model of Hindemithian sound, and which has in it all the things we've talked about tenderness, joy, vigor, — and cross-relations and bitonality — and much more, I think after we play this you'll understand what I mean when I say he was a great German composer, "Mathis der Maler" in English means Mathis the Painter: and this title refers to Mathis Gruenwald, a famous German painter who lived and worked way back in the early 16th century. For various reasons, Hindemith was strongly attracted by the paintings and the life-story of this painter Gruenwald; and so he decided to write a long, dramatic opera about him; an opera, not a symphony.

One reason was, of course, that Hindemith admired the beauty of Gruenwald's paintings, and the deep religious faith to be found in them. But a more important reason had to do with the struggle Hindemith was having with the Nazi government of Germany. Mathis Gruenwald had also had such a struggle, 400 years earlier, when he found himself caught up in the religious wars between the Protestant peasants and the Catholic nobles. He was torn between two loyalties; but he had even a rougher conflict between his sense of beauty, as an artist, and his sense of duty as a citizen. Which is more important, at a time of war and crisis and bloodshed — to take part in the struggle, to give your life to the cause, or to stay home and paint pictures?

This was exactly the problem that Hindemith himself was facing in the early 1930's: should a composer just go on writing his wind quintets and piano sonatas while the Nazis are turning his country into an armed prison camp, or should he stand up and fight? Should he knuckle under, and write the kind of music the government commands him to write, or should he stick to his guns? You're all too young to remember, but in those days the Nazis were burning books by the thousands, suppressing freedom on all sides, locking up anyone who didn't agree with their insane theories. And here was Hindemith, a free, creative soul, in a country where he couldn't be free. He didn't agree with the Nazi Theories, and the Nazis certainly didn't agree with his music. So this opera about Mathis der Maler was his way of protesting; and in it he solved Gruenwald's problem as well as his own, by deciding that an artist is also a citizen and a fighter, only his way of fighting is by practicing his art, by creating beauty, in his own way — even if it means leaving his country, forever, which Hindemith finally did in 1938.

Now what we're going to hear is not that whole opera, of course, but three orchestral sections Hindemith took from it, and put together to form three movements of a symphony. Each of these movements has a title, which is copied from the titles of three famous pictures that Mathis Gruenwald painted to adorn the altar of the church at Isenheim. The first picture — and the first movement of the symphony — is called Engelkonzert, or the Concert of Angels.

Do you see how light and lovely it is? Here are the Virgin and Child being serenaded by a band of shining angels, all in white, crimson and gold. It is all radiant with sweetness and gladness, and so is the corresponding music by Hindemith. It is a charming, lively, and very tonal piece of music, in the key of G. In fact, the very first chord you hear in this Angel-Concert is a pure G-major triad.

[PLAY]

Nothing can be more tonal than that.

Of course, right after that chord comes one of those cross-relations we talked about.

[PLAY]

That Bb crosses against the B natural in the chord

[PLAY]

— but it doesn't disturb the tonality. That's the main thing: no matter how far afield the music wanders, it always centers around a definite, clear tonality. In fact this 1st movement of Mathis der Maler is one of the clearest, most appealing pieces Hindemith ever wrote. It has a lovely, calm introduction, which quotes an old German melody "Es sungen drei Engel" (Three Angels Were Singing)

[PLAY]

— and it's all bathed in the soft glow of the G-major chord.

[PLAY (MORE)]

Then the main, fast part of the movement begins, first with this famous theme:

[PLAY]

Do you hear the cross-relation there? F# and F natural, side by side.

[PLAY]

It just adds a little spice, that's all. And the other tunes in the movement are all equally charming and jolly. The piece develops by juggling all the tunes around together in counterpoint, and it all ends in a dazzling burst of angelic light, like the Gruenwald painting itself. Here now is the 1st movement of Hindemith's symphony, "Mathis der Maler".

HINDEMITH: "MATHIS DER MALER" I. CONCERT OF ANGELS

I don't think anyone would call that 1st movement of "Mathis der Maler" difficult, or atonal, or lacking in melody. It's all joy from beginning to end. But now we come to the 2nd picture, and the second movement of Hindemith's symphony - and this is all grief and sadness. It's very brief — only four minutes — but it packs an awful lot of emotion and power into that brief span. This movement is called Grablegung, or in English, The Entombment, after the Gruenwald painting that shows the body of Christ being laid in the tomb.

You see how simple it is, how bare and stark. I don't know if you can see the faces of the mourning women but they are heartbreaking in their sorrow. The music catches this mood perfectly — also bare and stark, and with halting rhythms, like faltering footsteps of mourners.

[PLAY]

and with sighing harmonies

[PLAY]

and with long, comforting melodies. I think everyone agrees that, this little movement is the most beautiful thing Hindemith ever wrote. Here it is.

HINDEMITH: "MATHIS DER MALER" II. THE ENTOMBMENT

And now the third picture — the biggest and most complicated.

This is The Temptation of St. Anthony, showing the saint being plagued and tortured by all kinds of monsters and demons. And to match this grotesque, scary atmosphere, Hindemith begins his last movement with the only music in the symphony that might be considered "atonal"; it seems like a powerful free improvisation for the whole orchestra, and at the very beginning it sounds like a 12-tone row, but not quite.

[PLAY]

That's as close as Hindemith comes to atonal music; but it's exactly right in this place, because it describes the feeling of tension and agony with amazing accuracy. After this dramatic introduction, the main, fast body of the movement follows — wildly fast and exciting, like a mad chase.

[PLAY (MORE)]

But toward the end, when the notes are flying thick and fast in the strings, the wind instruments sing out a shining melody of salvation — the old chorale Lauda Sion Salvatorem

[PLAY]

— and then finally the brass sings out an Alleluia, so brilliant and strong that you actually feel the salvation of St. Anthony, of Gruenwald, of Hindemith, and ultimately of Germany itself. So in his inspired music, Hindemith tells us not only of 3 pictures by Gruenwald, but of greatness, of faith, and of hope for all men. If he had never written anything but this symphony, we would owe him our gratitude forever. And as we listen to this last movement of "Mathis der Maler," let us be grateful that for 68 years Paul Hindemith was part of our world.

HINDEMITH: "MATHIS DER MALER" III. TEMPTATION OF ST. ANTHONY"

END

© 1964, Amberson Holdings LLC.

All rights reserved.