Lectures/Scripts/WritingsTelevision ScriptsYoung People's ConcertsA Tribute to Teachers

Young People's Concert

Tribute to Teachers

Written by Leonard Bernstein

Original CBS Television Network Broadcast Date: 29 November 1963

LEONARD BERNSTEIN:

My dear young friends: You may think it strange that I have chosen to open this new season with the subject of teachers. After all, aren't these programs always about music? And what have teachers got to do with music? The answer is: everything. We can all think of a self-taught painter or writer, but it is almost impossible to imagine a professional musician who doesn't owe something to one teacher or another. The trouble is that we don't always realize how important teachers are, in music or in anything else. Teaching is probably the noblest profession in the world — the most unselfish, difficult, and honorable profession. It is also the most unappreciated, underrated, underpaid, and underpraised profession in the world.

And so today we are going to praise teachers. And the best way I can think of for me to do this is by paying tribute to some of my own teachers, who, over the last 30 years, have given me so much musical joy and inspiration.

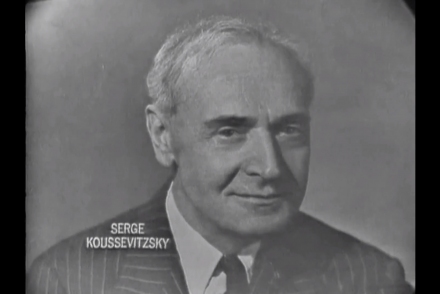

I want to begin with a teacher who is still one of the strongest influences in my life, even though he has been dead now for 12 years — Serge Koussevitzky. I am not sure how many of you young people know that famous name, but you ought to. He was one of the greatest conductors of all time, and for 25 years led the magnificent Boston Symphony Orchestra to a position where it was known as the finest orchestra in the world.

On top of that, he created the famous summer school at Tanglewood, known as The Berkshire Music Center; and it was there, in 1940, that I was lucky enough to become his pupil, and eventually his close friend. I would like to start our music today with a tribute to his memory. Koussevitzky was a Russian, and he dearly loved Russian music. So we are going to play a Russian piece that was a great favorite of his: The lovely, quiet prelude to Mussorgsky's opera Khovanshchina. That's a long name, but it's a very short piece; it describes the sunrise on the Moscow River; everything still and sleepy, interrupted only by the occasional crowing of roosters, and the booming of bells from the Moscow steeples. When Koussevitzky played this music he managed to produce an almost magic spell, which we, his students, still remember in our ears; and his performance remains a model we can strive all our lives to equal. Here is the Prelude to Mossorgsky's opera Khovanshchina.

I wish you could all have heard that beautiful little piece played by Koussevitzky. And the same magic he brought to it he brought to everything he did, especially to his teaching. He got through to his pupils by simply inspiring them. He taught everything through feeling, through instinct and emotion. Even the purely mechanical matter of beating time, of conducting four beats in a bar, became an emotional experience, not a mathematical one. I can hear his voice now, showing me how he wanted me to beat a slow tempo of four beats, smoothly, or as musicians say, legato. "Von-end-two-end-tri-end-four-end.... It most be vorm, vorm like de sonn!"

It was always a question of what happened between the beats; how the music moved from one beat to the next: Von-end-two-end-tri-end-four-end...; and the beats came to life. It became an exciting experience just to beat time.

You see, teaching is not just a dry business of scales and exercises; a great teacher is one who can light a spark in you, the spark that sets you on fire with enthusiasm for music, or for whatever you are studying. You can study the history of the Civil War for a year, memorizing battles and generals and dates and places; but if you don't care about the Civil War you'll wind up not knowing a bloody thing about it;

But if you're lucky enough to have a teacher who makes that war part of your life, part of your country and your past — then you can drink in whole gallons of dates and names and places, and never forget them, because you learned them out of enthusiasm. Koussevitzky was such a teacher. He lit those sparks. I wish he were here with us today. But we are privileged in having with us his gracious wife, who is, in her own way, just as inspiring as he was.

Mme K, do you remember the first work I ever conducted under your husband's guidance? I know I'll never forget it, because it was the first work I ever conducted in public at all. It was the 2nd Symphony by Randall Thompson, the distinguished American composer, who by a curious coincidence, was also one of my teachers. I had been studying orchestration with him at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia; and I shall always be thankful to him for the insights he gave me into orchestration, how instruments work, blend, and combine into an orchestra. And so I want to pay a musical tribute to Randall Thompson. We are going to play the 3rd movement from that same Symphony No. 2 that I conducted way back in 1940. This movement is a wonderful sort of jazzy scherzo; and I'll never forget what a challenge it was to conduct, at the age of 21, (and in my first public concert!) — because the rhythms are so tricky.

But any of you who ever listen to Dave Brubeck or Stan Kenton will feel right at home in this piece; it's great fun, and strictly American. Here is the scherzo from Randall Thompson's 2nd Symphony.

Out of all the teachers I've had in my life — and I'd guess roughly there have been 60 or 70 — there are at least 2 dozen I would want to thank for the excitement and inspiration they brought me. Of course I can't do that today; there isn't time; but I would like to mention a few of the most important ones, so I can share with you my eternal gratitude to them.

For instance, there was the great Professor David Prall at Harvard, who taught me philosophy and aesthetics like a blazing illumination; Edward Burlingame Hill, that fine American composer, who first opened my eyes to orchestration; Heinrich Gebhard, the great piano teacher of Boston, who made every lesson a ride on a magic carpet: Isabella Vengerova — oh, how I miss that great lady, that adorable tyrant who forced me to listen to myself when I played the piano. And so many others: Richard Stoehr, Susan Williams — I won't go on with this list of names. But I'm happy to say that some of them have been kind enough to come here today and be with us: and for that I feel proud and honored.) Here is Philip Marson, who long years ago at Boston Latin School drew back the curtain for me on the wonders of the English language, of poetry and rhythm, who through his love of words made me fall in love with them too.

And here is Helen Coates, who 30 years ago gave me my first really important piano lessons; and who for almost 20 years has been my devoted and overworked secretary.

And Renee Longy, who taught me the art of reading orchestra scores at the Curtis institute, and shared with me many exciting new discoveries in modern music.

And Tillman Merritt, whose brilliant and original way of teaching counterpoint and harmony I have never found equaled. He was also my tutor at Harvard, and I owe him a particular debt of gratitude.

Now I want to make a very special tribute to one of the foremost composers of our country, Walter Piston, who this season is celebrating his 70th birthday. Anyone who has ever had the good fortune to study with Piston can never forget the deep understanding of music he was able to communicate, or the deep belly-laughter that went with all our classes; he is certainly one of the wittiest minds I have ever known. And in honor of his 70th birthday, we are going to play his most popular piece — the suite from his ballet The Incredible Flutist. I'm not going to bother you with the story except to say it's about a circus that arrives in a Sleepy Spanish town; that one of the circus acts is an incredible flutist. Everybody dances: Tango, fandango, Spanish waltzes and polkas, but It really doesn't matter why; the music is what's important, and it's a delight to hear.

Now here is Walter Piston's Ballet-Suite The Incredible Flutist, which we are playing as a birthday tribute to a marvelous composer, a lovable man, and an inspired teacher.

I have saved the best for last: my greatest living teacher, also probably the greatest conductor in the world today — Fritz Reiner, who gave me my first baby lessons in conducting.

Reiner didn't use the Inspirational Method of Koussevitzky; there were no poetic speeches about the warm sun; there was only hard work, impossibly high standards of knowledge, and the all-important law of economy; every gesture must be concentrated on getting the orchestra to produce the sound you want — no, the sound the composer wants.

And so I want to pay my musical tribute to Dr. Reiner by playing for him, and for you, The Academic Festival Overture by Brahms.

I have two reasons for choosing this piece; one because it was with this overture that I first auditioned for Reiner, to get accepted into his conducting class at the Curtis Institute. And so I always think of The Academic Festival Overture whenever I think of Reiner. But the second reason is more important,

You see, Brahms wrote this overture in honor of a school — the University of Breslau, in Germany; and he even put into it four famous student songs — all old favorites of the University students, as a way of honoring them. So the Academic Festival overture is really a tribute to learning to students and to teachers. And it is in that spirit that we play it now; to honor not only Fritz Reiner, but all the great teachers on earth who work so hard to give young people a world that is a better, richer, and more civilized place.

[ANNOUNCER V.O., TV broadcast only: "Mr. Bernstein has asked us to tell you that in the short time since the taping of this program, Fritz Reiner died after a short illness. He would have been 75 years old next month."]

END

© 1963, Amberson Holdings LLC.

All rights reserved.

Watch a video excerpt of "A Tribute to Teachers"

Bernstein with conductor Serge Koussevitzky after performance of The Age of Anxiety, Symphony No. 2 at Tanglewood, August 11, 1949.  https://www.loc.gov/item/lbphotos.49a046/

https://www.loc.gov/item/lbphotos.49a046/