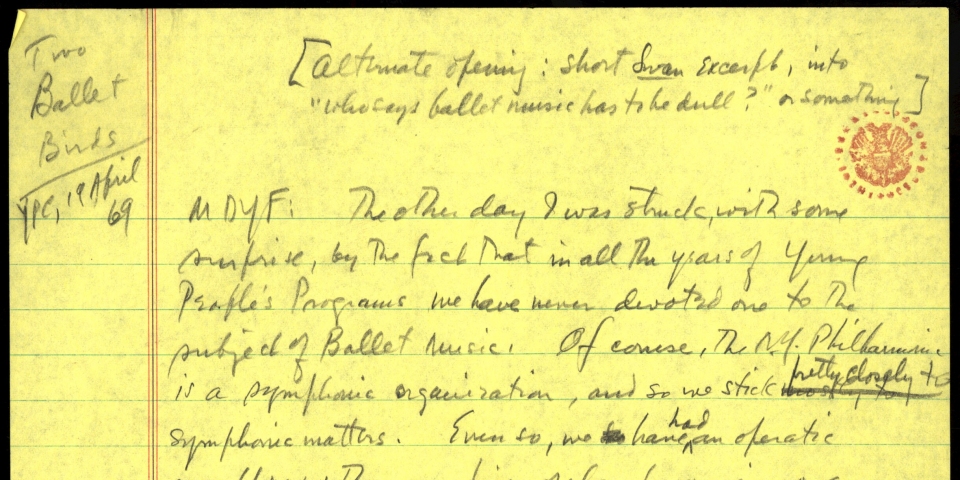

Lectures/Scripts/WritingsTelevision ScriptsYoung People's ConcertsTwo Ballet Birds

Young People's Concert

Two Ballet Birds

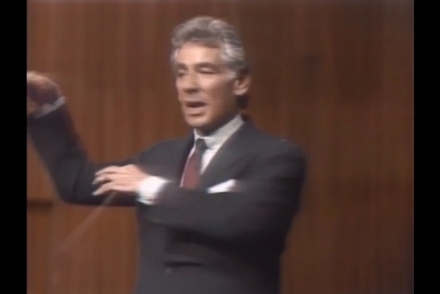

Written by Leonard Bernstein

Original CBS Television Network Broadcast Date: 14 September 1969

That haunting and original piece of music is from a ballet by Tchaikovsky called Swan Lake. Now who says ballet music is not good without the ballet? Well, many people say so, which, I suppose, is why ballet music rarely gets played on symphony programs. But after all, I ask myself, why not? There is so much wonderful music to be found within certain ballets that if we choose our program wisely and well we can have a ball. We might even learn something. Who knows?

So, we're going to limit ourselves today to only two ballet scores: Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake and Stravinsky's Firebird, both great and popular ballets, and both about birds. Now, why birds? Well, I guess birds are a natural symbol in ballet, because they fly, and flying is the age-old dream of man, and ballet is the perfect place for man to dream of flying, man being an earthbound creature in whom there has always been a deep desire for the freedom of flight, the defiance of gravity. And so the soaring Swan and the flying Firebird are symbolically the very heart of ballet. But enough about the birds. What else do these two ballets have in common? Well, first off, they both have music by exceptional composers, perhaps the two greatest figures in all Russian music. Tchaikovsky, of course, is of the nineteenth century, while Stravinsky is very much of the twentieth. And yet they are closer than you think, because if you look at the dates of the two ballets you find, amazingly enough, that there is only one generation, roughly thirty years, separating the two ballets—a decade or two on either side of that 1900 year line. And besides Stravinsky has always been a Tchaikovsky lover: He even wrote a whole ballet based on Tchaikovsky themes.

But Swan Lake and Firebird have even more in common than that. Because they are both romantic story-ballets, they are both filled with magic, and both concerned with the forces of good versus evil, with evil finally conquered by love.

And in both ballets there is a dreadful villain, a hero-prince who goes hunting, an enchanted heroine, and all the customary ingredients of fairy tales, myths and legends, but there the similarities end, and we now come to what this concert is really about—namely, the differences between the two ballets. That's what's really interesting. Naturally we can't go into all of these differences, or we'd never get to the music. I'd like to go directly into the main and most interesting difference, which does get us right to the music. And that is this: You see, there are two basic kinds of ballet: One kind tells a story, and the other kind doesn't. Simple. Now, this second kind is what is called "abstract" ballet—that is, pure dance, dance for its own sake, for the delight of movement, of patterns and forms, and for the interpretation of music through the motions of the human body. Now some ballets are totally abstract, no plot at all (for example, Les Sylphides with music by Chopin; it is all dance and no story), whereas other ballets are all story, from beginning to end, like Stravinsky's Firebird, which you're going to hear later. But Swan Lake is a combination of both; that is, it has a tale to tell (much of the dancing centers about the adventures of the hero-prince, the Swan Queen heroine, and the nasty magician-villain), but the ballet is also full of separate set pieces, that is, dances that have almost nothing to do with the story. They're just entertainment, momentary diversions, comedy interludes, or sheer acrobatics. Such numbers are often shifted about from one spot to another, or even from one act to another, or they're shortened, or reorchestrated, or even cut out completely, depending on the taste of the choreographer who happens to be in charge of any given production. In other words, they are expendable and even interchangeable. And yet, strangely enough, it is these very numbers that give Swan Lake its classical quality, that make it part of the old tradition of classical dancing for its own sake. Can you understand that? In other words, Swan Lake is both romantic and classical, it's both narrative and abstract.

So, for these reasons, the music we're going to play from Swan Lake will be of the abstract kind, having little if anything to do with the story—just to point up the difference between it and Firebird, which is all story music. Now, we're going to start with what is called a pas de deux, which means a dance for two people, a duet. Now a pas de deux can be any kind of dance, slow or fast, long, short, for male or female dancers. But the classical pas de deux, as developed by the great traditional choreographers, has to follow a certain prescribed form—which is what makes it classical, of course, and this form is a sort of suite, that is, a group of several pieces, usually four in number, danced by the leading male star and the leading female star of the company. She is known as the "prima ballerina," and he as the "premier danseur." Why she is in Italian and he is in French is one of those great unsolved mysteries. Anyway, there they are with a four-part suite to dance. The first part is for the two of them and almost always includes what is called an adagio, or a slow dance of love featuring the ballerina, who is partnered, supported, lifted, escorted, and otherwise gallantly attended by her noble danseur. Then after much applause and bowing, the ballerina retires to the wings and there follows the so-called male variation, usually a vigorous show-off piece in which the man does his utmost to defy gravity. Then comes the third part, the female variation, a more graceful solo for the lady. And finally, Part IV, which is known as the coda, an exciting, brilliant finish for both dancers, calculated to bring down the house.

Now this pas de deux from Swan Lake we're about to play is one of those shifting numbers I was talking about, which is to be found in Act One of the original score of Swan Lake, but more often in these days appears in Act Three, under the title of the Black Swan pas de deux. So you can see that its connection with the story line is at best a rather loose one, and I won't even bother you with it. Let's just listen to this charming, abstract dance music. Now first, here is Part I, which is a short opening waltz leading to that romantic adagio, or love duet.

Bravo, as always, David Nadien. Now, on that last high violin trill of his, the ballerina, who has finished in a dangerously balanced position on toe-point supported by her partner, is suddenly left unsupported by him for a brief, hair-raising moment. The audience gasps and then screams with joy. Now it's the male dancer's turn—poor man, he's done almost nothing for three acts but serve the ballerina as supporting partner—and now in this tiny variation he gets his one big change to pull out all the stops and display his virtuosity. This variation is less than a minute long, but if our hero really does his stuff, well, it can last two or three times that length, owing to interruptions of unrestrained applause and yelling of "Bravo." In fact, the first time I ever attended a performance of this pas de deux, the whole male variation was drowned out by applause, so that I never even knew how the music went after the first couple of notes. So listen hard: This may be your only chance to hear this piece from beginning to end.

I wish I could dance that. Now, if you can imagine two or three minutes of frantic applause and screaming, you can also imagine how hard it is for anybody to follow that act, even the ballerina herself. But she has to; this is her solo variation. And if she plays her cards right, by being winning and sweet, and slyly underplaying her star role, she can even top her partner's ovation. Now, here she comes, the ravishing Black Swan.

That's a very sweet piece. And now the topper of toppers, the coda, with the glamorous couple dancing together, then separately, then together again, thrill after thrill. They fly, leap, jump, compete with each other for glory, and the audience goes wild. Now, if all this sounds a little bit like a circus, don't worry; it is a kind of circus, of a very lofty kind. Now hold your hats: here comes the coda.

You know, I think it's some kind of first to have spent this much time on Swan Lake without telling you the story at all. But, story-telling time has arrived because now we come to the Firebird, which is a ballet that's all story. No waltzes, no incidental, irrelevant numbers, like that last one. Every note of this Firebird music is tightly woven into the story, making a marvelous tapestry of sound. There's no question here, as there must have been in Swan Lake, of the composer being the slave of the choreographer, supplying music on demand, by the yard or by the bar—an extra eight bars here, sixteen bars there, for the further glory of the male variation, or to give the choreographer time to get his swans off the stage. There's nothing like that. Igor Stravinsky is in command here, making the music and story all of one piece. So I think it might be a good idea this time to tell you the Firebird story, as briefly as I can, so that you can enjoy the music that much more.

It's based on an old Russian fairy tale about a young prince—named Ivan, of course—who goes hunting, and finds himself in an enchanted forest. He hears a sound in the trees, draws his bow to shoot, and stops amazed when he sees that his victim is a glorious creature, half-bird, half-woman, in feathers of fire, scarlet, gold, orange, purple. The prince wants, of course, to capture this radiant figure: She is doubly desirable; as a fabulous bird and as a beautiful girl. Which I suppose these days mean the same thing. Anyway, he grabs her, and they struggle, and the Firebird pleads with him to free her. Ivan is touched by pity and love, and when he does release her she gives him, out of gratitude, one of her red feathers which, she says in ballet pantomime, has magic powers and will protect him against all evil. And then she disappears into the night.

Suddenly the scene is transformed and Prince Ivan finds himself in a lovely garden, also enchanted, where a bevy of charming young princesses are amusing themselves by playing catch with apples. Don't ask me why. It turns out that they are all prisoners in this garden of the evil monster Kastchei, the king of demons and devils. Of course Ivan falls instantly in love with the most beautiful princess, as in all such stories, at which point nasty old Kastchei descends upon them with all his ugly company of horrid little monsters. But Ivan has the magic feather and fearlessly wards off this mass attack until the climactic arrival of the Firebird herself, who hands him a golden sword with which he terminates Kastchei's power, and indeed his existence. As Kastchei dies his demons collapse as well; the princesses are freed, the Firebird puts all the evil spirits to sleep forever, and flies away. All is well. And there remains only the happy-ever-after scene, at Prince Ivan's court, where the great royal wedding takes place before all his loving, kneeling vassals.

Now that's a dandy little bedtime story, but it doesn't give you any of the real feeling of this legend—the sense of very ancient times, of primitive people, of a fantasy world in which everything is made of mystery and wonder.

But all this can be told you most eloquently by Stravinsky's music, so let's not wait any longer. We are going to play not the whole ballet, but a suite from it made by Stravinsky himself, which contains most of the high points of the ballet. It starts with a mysterious, dreamlike introduction, filled with forest sounds that are not of this earth. Then suddenly the orchestra flashes, the Firebird appears and does her solo dance. Here is that first part.

Glorious music. Now Stravinsky's suite skips to the enchanted garden, where the princesses are dancing elegantly to music full of grace and Russian lyricism. This is interrupted by a crash that may make you jump out of your seats, as Kastchei and all his ghastly crew fill the stage with horror. Here are those two dances: First of the princesses and then of the monsters.

Wow! Those monsters can really take it out of you. But now for the end. Kastchei is a goner, and we now hear the famous Russian lullaby with which the Firebird puts all the demons to eternal sleep. The transition from this lullaby to the final scene is one of the most magical moments in all music. Everything is paralyzed with sleep and stillness, and the music hovers in the air with extraordinary shifting harmonies that actually seem to convey the presence of the supernatural. And suddenly, as if from nowhere, comes that famous horn solo, an ancient Russian folk melody—quiet, noble, filled with dignity. And in that moment the air is cleared, we are back in real life, at Prince Ivan's court, at the wedding. It is a miraculous transformation. And as this horn melody repeats and repeats throughout the orchestra, growing in intensity and grandeur, we behold a spectacle of old Russia that is unforgettable in its glory. You don't even have to see the stage: The music tells you everything. This music does honor to the art of ballet, and to music, and to Stravinsky himself, the greatest master our century has produced.

END

© 1969, Amberson Holdings LLC.

All rights reserved.