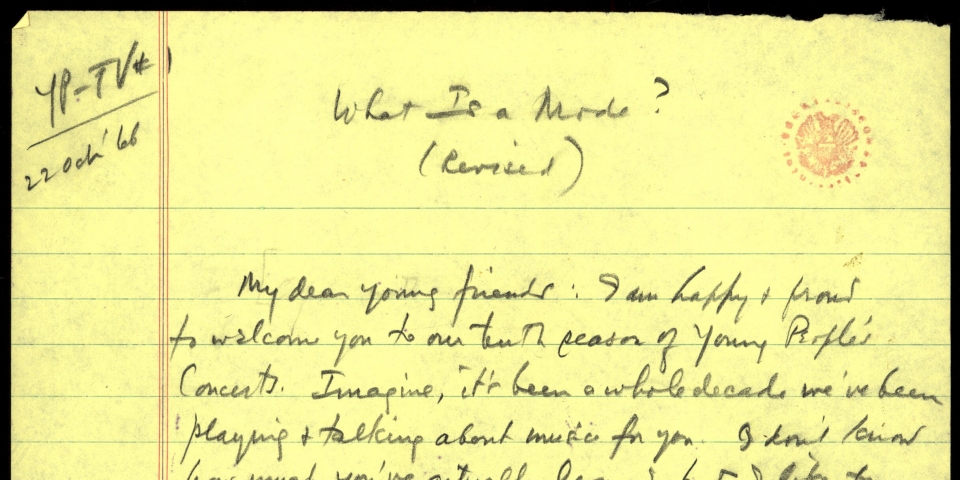

Lectures/Scripts/WritingsTelevision ScriptsYoung People's ConcertsWhat Is a Mode?

Young People's Concert

What Is a Mode?

Written by Leonard Bernstein

Original CBS Television Network Broadcast Date: 23 November 1966

LEONARD BERNSTEIN:

My dear young friends: I am happy and proud to welcome you to our tenth season of Young People's Concerts. Imagine, it's been a whole decade we've been playing and talking about music for you. And I don't know how much you've actually learned, but I like to think we must be doing something right, because—well, because it's our tenth season. And to add to the festivities, this is also the first season in which all our programs will be seen on television in color. Which is why I've got this modishly colorful tie on.

And that brings us to our subject: What is a mode? Well, for one thing, musical modes have nothing to do with neckties, or dresses, or even with fashions of a musical kind. Modes are simply scales, though not perhaps those very scales you practice on your piano. They are rather special scales; and I wouldn't have dreamed of bothering you with them, except for an incident that happened a few months ago. My fourteen-year-old daughter Jamie happened to ask me one day why a certain Beatles song had such funny harmony; she couldn't seem to find the right chords for it on her guitar. And I began to explain to her that the song was modal; that is, it was based on what is called a mode. And I went on to show her the chords that come from that mode—and she got so excited she wanted to know more and more about it, until finally she said: "Why not tell all this on a Young People's Program? Nobody ever heard of modes!" Well, I thought, Jamie is just a natural music lover with the usual weekly piano lesson, and if she finds this material fascinating, why shouldn't you? So here goes, and you can blame it all on Jamie.

O.K. We already know that a mode is a scale. But, first of all, what is a scale? I'm sure you know, but maybe you've never tried to put it into words. Well, a scale is simply a way of dividing up the distance between any note

and the same note repeated an octave higher.

The most famous and often used division of this octave range in our Western music is what we call the major scale.

I guess you all know that one. And the other famous one is the minor scale.

I guess you know that too. Now what's the difference between the major and the minor? Many people think the only difference is that the major scales sound happy, and the minor ones sound sad. Well, that's sometimes true, but not always. The real difference is in the arrangement of the intervals—you remember how deeply we dug into intervals last season? And you remember we found that the smallest interval—that is, the distance from any note to its nearest neighbor—is called a halftone. So from C to C-sharp is a step of a halftone. And from C-sharp to D is again a halftone. So it would stand to reason that from C straight to D is a whole tone, since two halves make a whole. Get it? Fine. Now this entire C-major scale is nothing but a series of whole tones and halftones arranged in a special order: C to D, a whole tone; D to E, again a whole tone; E to F, a halftone (since we've skipped nothing); then three whole tones: first two whole tones, 1 and 2, then a half tone, then three whole tones, then a half tone. That's a major scale.

And the minor scale is almost the same arrangement of intervals, the main difference being in the third note of the scale,

which in the minor is a halftone lower,

so that the minor scale sounds like this:

And it doesn't matter whether you start on C or on E-flat or Q-sharp, you can always get a major or a minor scale by following the proper arrangement of intervals.

For instance, here's a major scale beginning on F# and that's called F# major. And here is F# minor. And here's a major scale beginning on Bb, so that's Bb major. And here's Bb minor, and so it goes. But the important thing to remember about mode is that major and minor, are modes. But they are only two modes out of a much larger number of possible ones. Now before I tell you anything else about modes, we are going to play you a short but marvelous piece, by the great French composer Debussy. This piece is completely based on modes that are neither major nor minor.

This brilliant piece, which is called Festivals, or, in French, Fêtes, uses all kinds of other modes which, of course, you won't know about yet; you'll just be hearing beautiful sounds that will seem a bit strange and ear-tickling. But we're going to play it again later, at the end of this program, and I'm sure that by then you'll be able to recognize most of the peculiar things that are going on. So, for the moment, just enjoy it and imagine a splendid nighttime celebration, with many-colored lights and lanterns everywhere, gorgeous fireworks in the sky, and everyone dancing in costumes of long ago. And suddenly, in the middle of the piece, the dance music breaks off, and we faintly hear a procession in the far distance. This march-like music comes nearer and nearer, and when it finally arrives in all its glory the dance music and the march music are heard together in an exciting blend of tumultuous sounds. And finally, at the end of the piece, it grows late, the crowds thin out—as does the music—and it all ends in a whisper, with an echo or two of the night's festivities hanging in the silent air. Here is Debussy's Fêtes.

How about that for an exciting piece? I found it positively goosefleshy. And a lot of the excitement comes from the fact that it uses those strange scales, or modes, which are neither major nor minor. For instance, right at the beginning appears that first swirling dance tune,

which sounds at first like the usual minor mode.

In fact, the first five notes

of it are exactly the first five notes of the minor scale: But then comes the twist.

These notes

don't belong to any minor scale we know.

So what scale is this?

Answer: It's the scale of the Dorian mode. Now don't let that throw you: Keep calm, sit back, and let's quietly find out just what this Dorian mode is, and why it sounds so special.

The word Dorian obviously comes from the Greek, and in fact, as well as the other modes we're about to discover, does come originally from the music of ancient Greece. We don't know too much about that old Greek music: What we do know is that the Greek modes eventually made their way to Rome and were taken up by the Roman Catholic church during the Middle Ages in a somewhat different form. But the church kept the old Greek names for the modes: Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian, Locrian, and Ionian. Now there's a mouthful for you. I know. But they're much easier to understand than their names are to pronounce. And they are still used today in Catholic churches all over the world, in those beautiful chants called plainsong. Here is a tiny example of plainsong, in the Dorian mode:

Isn't that beautiful. I bet you didn't know they could sing too, did you? You just witnessed the debut of a great new glee club. Anyway. That is music in the Dorian mode, using exactly the same scale, the same arrangement of intervals, as Debussy used in his Fêtes. But what is this scale? Ah, that's easy. To find the Dorian mode on your piano, all you have to do is to start on the note D

and play only white notes all the way up to the next D,

and you've got it. Simple. And that's true of all the other church modes as well—they're all to be found by starting on a given white note and making a scale up using white notes only. Isn't that lucky? And we're particularly lucky with the Dorian mode, because it starts on D, and D is the first letter of the word Dorian! So you have no excuse for forgetting how to find this mode on your piano: Dorian, capital D, note D,

white notes all the way up

and voilá!

Now here's another piece in the Dorian mode—I wonder if you know this one.

Along comes Mary, in the ancient and honorable Dorian mode—the same mode we just heard in Debussy and in the plain-chant. Now who'd have thunk it? What is that old Greek mode doing in today's pop music? Well, I'll tell you. From about the time of Bach until the beginning of our own century—roughly two hundred years—our Western music has been based almost exclusively on only two modes—the major and the minor. I can't go into the whys and wherefores of it now, but it's true. And since most of the music we hear in concerts today was written during that two hundred-year period, we get to think that major and minor modes are all there are. But the history of music is much longer than a mere two hundred years. There was an awful lot of music sung and played before Bach, using all kinds of other modes. And in the music of our own century, when composers have gotten tired of being stuck with major and minor all the time, there has been a big revival of those old pre-Bach modes. That's why Debussy used them so much, and other modern composers like Hindemith and Stravinsky, and almost all the young song writers of today's exciting pop music scene.

The modes have provided them with a fresh sound, a relief from that old, overused major and minor. For instance, if that swinging opening of Along Comes Mary had been written in the usual, everyday minor mode, it would sound like this.

Sort of square, isn't it? Ordinary. But this,

this has a kick in it, and the kick is Dorian.

You can see that this Dorian mode is almost like an ordinary minor mode, but not quite. And that not quite is what makes the big difference, and that difference gives the music a certain ancient, primitive, Oriental feeling. That's why the plain chant we heard before is so stirring, so ancient as to seem timeless. And that's why the tune in Debussy's Fêtes seems so exotic and of another age. And that's why Along Comes Mary sounds so primitive, and earthy. Now by way of contrast listen to this opening section of Sibelius's Sixth Symphony, which is also in the Dorian mode, and see if you can feel again that same timeless, brooding, ancient, far-off quality, only this time coming from the remote, lonely forests of Finland:

Do you see what I mean by the special feeling of the Dorian mode? Are you beginning to get the sound of it in your ears? Well, let's get technical just for a minute, and find out exactly what it is that gives us this feeling. As we know, this Dorian mode

is practically like the usual minor mode

with one very big difference: in the minor mode the seventh note is called the "leading tone," because it leads us home to the keynote, or tonic,

which is D. And that leading tone leads us to the tonic by the smallest possible interval, namely a halftone. You see.

It's as though that leading tone were in love with the tonic and were pulled towards it. It wants to embrace it, wants to get there, which it does. But in the Dorian mode, where the 7th note is a half tone lower, there's a whole step between it and the tonic. So it just doesn't seem to lead as strongly; it's not in love with the tonic. It's friendly enough, but it just wants to shake hands. Do you feel how formal and modal that sounds, that Amen? The minute we hear that

"Amen," we feel behind it the weight of many centuries, of a different, older, more Eastern culture. Bach never wrote an "Amen" like that, and neither did Beethoven or Brahms. But in our own century it gets written all the time. For example, this:

That's no Amen, of course, but musically it's the same idea. Well, that's an awful lot about the Dorian mode—which, may you never forget as long as you live, starts on D. Dorian—D. Now, let's get on to the next one, which starts on E—the Phrygian mode. Again, this is terribly easy to find on the piano: you start on E,

again you play white notes up to the next E,

and there's your Phrygian mode.

Now this Phrygian mode is very much like the Dorian, in that it is a minor mode,

and it has that lowered seventh or leading tone.

You see again how that formal strange mode sounds. But it also has something else very unusual: It is the only mode that begins with a step of a halftone; that is, from the first note, E, to the second note, F, is a mere half step. And that gives the music a specially sad quality,

which can be heard in so much Spanish and Hebrew and gypsy music.

For instance, you all know the beginning of Liszt's famous Second Hungarian Rhapsody, don't you?

Do you hear that typical sad, gypsy sound?

That's the Phrygian mode for you. It's a very Oriental-sounding mode but has also been much used by Western composers, even during that famous two hundred-year non-modal period, especially when they wanted to create Oriental effects. Like this well-known spot in Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherezade—which, as you know, is wildly Oriental:

That's as Oriental as you can get. And it's pure Phrygian.

That's the Phrygian scale. But the real surprise is to find that even old very un-oriental Brahms from Germany has used this mode—very unusual for him—in the slow movement of his Fourth Symphony. I'm sure you've all heard this solemn and majestic phrase:

That's the sound of the Phrygian mode. Courtesy of Mr. Brahms.

All right, up we climb now to the next mode, which is called the Lydian. And this one, as you might guess, begins on F

and like the others uses only white notes all the way up the octave.

That's the Lydian mode. Now what makes this one different from the other two modes we've already talked about? Two things: first, that it is a major mode, as you can hear

the first one we've met so far, and second—well, let's see if you can tell me. I'm going to play you our normal scale of F major

and now the Lydian scale starting on F.

Now there's one very peculiar note in that mode—the only note that's different from the usual F-major scale. And I want you to tell me which note is the peculiar one, by clapping your hands the second you hear it. Is that a deal? OK. First, here's the normal F-major scale. And don't clap.

Now, the Lydian scale, and remember, you're going to clap when you hear the "wrong" note.

Good, great, exactly: it's that fourth note of the scale,

which is a halftone higher than the normal one. That's normal. Right. This is abnormal. Good. Right. Now you've got it out of your system.

Now that funny note gives this mode a very funny quality, almost comical, as if a wrong note were being played on purpose. In fact, several twentieth-century composers have taken advantage of this Lydian mode to get comic effects. For instance, Prokofiev, in his music for his funny film Lieutenant Kije, uses this mode, with its raised fourth note in this piccolo solo:

Could you detect that "wrong note"

If this had been written in the straight major scale, it would sound like this:

But no: Prokofiev adds his comic touch by using that Lydian raised fourth note:

But I don't want you to think that the Lydian mode is only comical. On the contrary, it can be a very serious mode indeed. In fact, Beethoven wrote a long, extremely serious movement of a string quartet in this very mode. And, of course, it's still used in Roman Catholic plain chant, in church. And again, Sibelius—who was always a great mode lover—was constantly using the Lydian mode, as in this passage from his Fourth Symphony:

Do you hear that Lydian note?

Only this time it's not a funny note, but a strange piercing note that seems to come from a faraway place. And that's only natural, because these modes do come from faraway places like the Middle East and eastern European countries like Greece, Bulgaria, Finland, Russia, Poland. In fact, Poland is one of the main breeding grounds for this Lydian mode. You constantly hear it in Polish folk music and in the works of Poland's greatest composer, who was Chopin, of course, especially when he was writing Polish-type nationalistic dance pieces, like polonaises and mazurkas. Here's a bit from one of his best-known mazurkas, and see if you can hear that Lydian sound:

It's an odd sound, isn't it?

So fresh and sharp, like the taste of lemon juice. And it's a very Polish sound. In fact, when the Russian composer Mussorgsky—now follow this—when the Russian composer Mussorgsky was writing the third act of his great opera Boris Godunov, an act which takes place in Poland, he used this same Polish Lydian mode for his Polonaise, which means "Polish dance." We're going to play it for you now, and listen for this tangy Lydian sound of the tone when you hear it.

Here it is with the orchestra playing.

Well so far we have had a good look at three important modes—the Dorian, the Phrygian and the Lydian—those white-note scales that start on D, on E, and on F, respectively. Now let's have a quick look at the remaining ones, starting with the mode that begins on G

and rises up though the octave on the white notes.

Now this one is called (don't panic!)—this one is called the Mixolydian mode, and despite its tongue-twisting name, it's one of the most appealing and popular modes of all. Again, like its neighbor, the Lydian, it's a major mode, as you can hear

and, also like the Lydian it has one peculiar note in it, only this time it's a different peculiar note. See if you can tell which it is. Here is a normal G-major scale.

Now here is the Mixolydian scale, and perhaps you care to clap again when you hear the one odd note.

Very fine: It's the seventh tone, the leading tone

which is half a tone lower than normal, for which you will not clap. Right? No. This is the normal one which is higher. This is the abnormal one. Right.

Now this is the only major mode that has a lowered leading tone, and believe it or not most of the jazz and Afro-Cuban music and rock-and-roll tunes we hear owe their very existence to this old Mixolydian mode. Like this Cuban riff.

That's just Mixolydian. Now, do you hear how that lowered seventh tone makes a jazz sound?

Of course, the examples I could give you are endless, but just to take a recent smash hit:

Mixolydian. Could you believe it? Or do you remember a really terrific, barbaric song a few years ago, such by a group called the Kinks. It's called You Really Got Me.

That's old Mixolydian. Or, I wonder if you know take that absolutely charming Beatles tune, called Norwegian Wood.

You hear that lowered seventh note?

That makes it Mixolydian. They're all Mixolydian. Now again, I don't want to give you the idea that this mode produces only jazz and pop music. It's still to be heard as much in churches as in discotheques. And, in fact, our old friend Debussy, when he wanted to suggest a Cathedral rising out of the sea (in that famous piano piece of his called The Sunken Cathedral used this same Mixolydian mode.

Isn't that a wonderfully impressive sound. I don't mean my sound; I mean Debussy's sound. And years ago, when I was writing my first ballet, Fancy Free, I also used Mixolydian mode for one of the dances. Since it was a Cuban-style dance called a danzon, I naturally used this mode from beginning to end, so it ought to make a good example. Here it is, and I hope you like it.

And now, in the few minutes that remain to us, I would like to pay my brief respects to the three modes we still haven't discussed. We can do this very quickly, as you will see, because the first one, known as the Aeolian mode (which luckily starts on A, making it easy to remember)

is almost like our normal minor scale using all the white notes;

in fact, it is sometimes referred to as the "natural minor" mode. Its one special feature is, again, that lowered leading tone

which makes it so similar to the Dorian and Phrygian modes that we don't even have to discuss it any further.

Then, the next mode, starting on B,

is known as the Locrian mode

and this we can really skip, because there is almost no music written in it. You see the Locrian mode is strangely unsatisfying, it doesn't seem to be conclusive, mainly because the tonic chord you get from it is terribly unsettled and inconclusive.

See what I mean? So hello and goodbye to the Locrian mode.

the starting note of our final and most triumphant mode of all, called the Ionian. Listen carefully now: Here is C,

and up we go, white notes only, to the next C,

and what have we got? Surprise: The C-major scale! The good old, tried and true C-major of Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms.

Now this C-major scale, once known as the Ionian, had simply survived better than all its neighbors the evolution of history and emerged in glory as king of all Western music for two hundred years. For instance, this tremendous C-major celebration by Beethoven.

That, that was the last 30 seconds of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony and there's no doubt that it's in C major. Beethoven doesn't leave any doubt about that. He hammers the point home.

Well, by now you've heard enough about modes, and heard enough examples of them, so that I think you're ready to hear Debussy's Fêtes again, and this time really connect with it. But just to refresh your memory: Do you recall that opening dancy tune in the Dorian mode?

And then, a little later on, Debussy switches to the Lydian mode. Do you remember? The one with the raised fourth note, that Polish one?

That's Lydian. Then, a few seconds later, he's suddenly in the Mixolydian mode—remember? The jazzy one with the lowered leading tone.

And so, in the first half-minute of the piece, Debussy has already used three different modes, none of them major or minor: Dorian, Lydian, and Mixolydian. Then, in that famous middle section, when the distant procession begins, we hear it first again in the Dorian:

That's Phrygian, but it immediately switches to Mixolydian:

And so it goes, one mode after the other, throughout that whole piece. Just before we play this for you, there is one thrilling spot in this piece that I'd like to prepare you for, so that you can enjoy it as much as possible: that wonderful moment when the procession music and the dance music come crashing together. The trick is, of course, that they're both in the Dorian mode, and so they make perfect mates. This is the dance music:

And here is the march music:

And here are the two musics together:

Isn't that a staggering sound? Now, listen to the entire piece; and I hope you enjoy it at least twice as much as the first time you heard it.

END

© 1966, Amberson Holdings LLC.

All rights reserved.