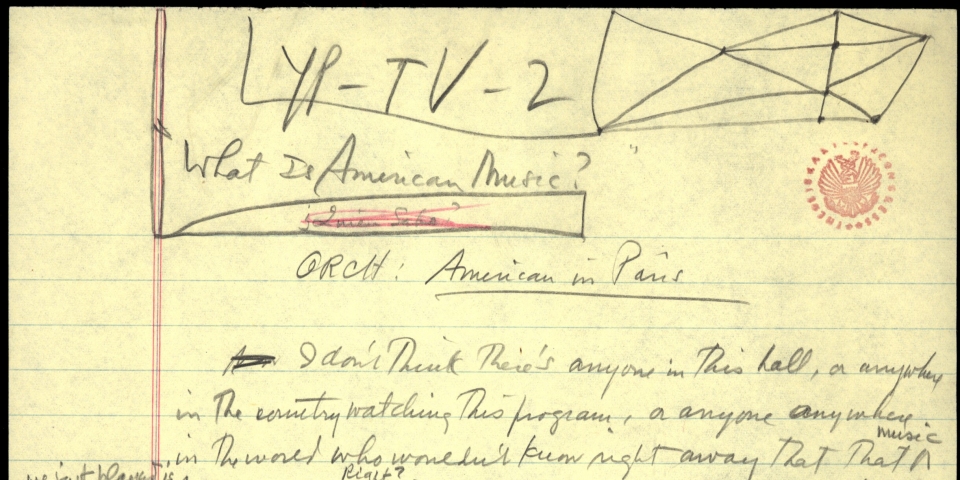

Lectures/Scripts/WritingsTelevision ScriptsYoung People's ConcertsWhat is American Music?

Young People's Concert

What is American Music?

Written by Leonard Bernstein

Original CBS Television Network Broadcast Date: 1 February 1958

LEONARD BERNSTEIN:

Hello again everybody. I'm awfully glad to see you all again, and I want to thank you all particularly for your wonderful letters and telegrams about our last show. They made us feel very happy and proud.

This time we're going to talk about what makes American music sound American, and just to start things off, here's some American music.

[ORCH: GERSHWIN: AN AMERICAN IN PARIS]

I don't think there's anybody in this hall, or anywhere in the country watching this program, for that matter, or anyone in the civilized world who wouldn't know right away that that music we just played is American music. It's got "America" written all over it—not just in the title, which is, you know, An American in Paris, and not just because the composer, Gershwin, was American, but it's in the music itself: it sounds American, smells American—makes you feel American when you hear it.

Now why is that? What makes certain music seems to belong to America, seem to belong to us? That's what we're going to try and find out today.

[TO PIANO]

Almost every country, or nation, has some kind of music that belongs to it, and sounds right and natural for its own people. When a nation has its own kind of music, we call that music "nationalistic" music. Sometimes it's just folk music, very simple songs—or sometimes not even songs; maybe just prayers for rain banged out on Congo drums,

[ILLUSTRATE]

or a sort of primitive chanting, in Arab style.

[ILLUSTRATE]

Or it can be dance music, like a Mazurka from Poland,

[ILLUSTRATE]

[PIANO: CHOPIN MAZURKA]

or could be a Tarantella from Italy.

[ILLUSTRATE]

[PIANO: TARANTELLA]

This is a piece I learned when I was eleven. I still can't play it very well. There.

Or it might be a reel from Ireland.

[ILLUSTRATE]

[PIANO: IRISH WASHERWOMAN]

The minute you hear that reel, you know it's Irish, just as you know the Mazurka was Polish or the Tarantella was Italian. Now you tell me what country this music makes you think of?

[ORCH: RAVEL: SPANISH RHAPSODY]

What country's that?

[KIDS RESPOND]

Spain. My goodness. You're, as you would say, "hep". Right. Now it's Spanish. You couldn't mistake that rhythm in a million years,

[SING]

or mistake those castanets,

or that tambourine.

That's Spanish. Now what country does this music make you think of?

[ORCH: BRAHMS HUNGARIAN #5—2ND STRAIN]

[KIDS RESPOND]

Hungary. Right again. Some of you said gypsy, some said Hungary. It's the same idea. It's as Hungarian as goulash. It's hard to miss that.

[SING CADENCE]

Now what about this?

[ORCH: TCHAIKOVSKY'S FOURTH]

[KIDS RESPOND]

Right. Right. You're all so smart today. That's Russian. You can't miss it—it's got to be Russian, because it has a Russian folk song in it—it has a tune that all Russians know and have sung since they were little kids. That tune, by the way, is called "The Little Birch Tree." And in Russian — I don't sing Russian very well — but it goes something like this:

[SING: "Vo poleh beriozinka stolyala

Vo poleh kudravaya stolyala

Luli, luli stolyala

Luli, luli stolyala"]

Well, Tchaikovsky used that tune in that symphony we just played, and that settles that symphony. It's Russian.

So you can understand that when this kind of music is played in the country it belongs to, all the people listening to it feel that it belongs to them, and that they belong to it—it's their music. Because in most countries, the people who live there are descended for hundreds of years from their forefathers, and their forefathers' forefathers, who all sang the same little tunes and sort of own them; so when the Russians hear a Tchaikovsky symphony, they feel closer to it than say, a Frenchman does, or than we do.

Now, how about us, here in America? What's our folk music? What did our forefathers sing? That's the problem. We all have different kinds of forefathers. For example: Mr. Corigliano, there, has Italian forefathers. And Varga has, Hun ... Varga's forefathers were, what were they? Hungarian. And mine were Jewish. Mr. McGinnis's were Scotch-Irish, and Mr. Wummers were Dutch, I believe, Dutch. And what about your forefathers? What about yours?

[POINTS TO VARIOUS KIDS AND ASKS]

Tell me about your forefathers. Can you tell? What about yours? Hungarian someone just said. What were yours? Polish? What were yours? Well, you can see we could be here all day listing all the forefathers that you have. We could be here for ages. Sweden, Spain, Hungary, England, Germany. They come from everywhere. But we haven't got hours to be here and list them all.

So you see that is our problem: the problem is that with all those different forefathers we have, what is it that we all have in common, that we could call our folk music — the folk music we've inherited? That's a tough question. You see, we haven't had a long time to develop a folk music. Don't forget, America is a very new country, compared to all those European ones — we're not even two hundred years old yet! And that's not very old for a country. We're still a baby—a big, fine, strong baby—but still a baby. And so our music is also still very young.

Actually, our real serious American music didn't even begin until about seventy-five years ago. At that time the few American composers we did have, were imitating European composers, like Brahms and Liszt and Wagner and all those. We might call that the kindergarten period of American music; our composers then were like happy, innocent little kids in kindergarten. For instance, we had a very fine composer named George W. Chadwick, who wrote expert music, and also deeply felt music, but you could almost not tell it apart from the music of Brahms, Wagner, or other Europeans. Like this overture of his. Listen.

[ORCH: CHADWICK: MELPOMENE]

You see, that's straight European stuff. But around the beginning of our twentieth century, American composers were beginning to feel funny about not writing American sounding music. And it took a foreigner to point this out to them—a Czechoslovakian composer named Dvorak, who came here on a visit and was amazed to find all the American composers writing the same kind of music he wrote. So he said to the American composers: "Look, why don't you use your own folk stuff in your own music, when you write? You've got marvelous stuff here—Indian music, which is, who are, the Indians are the real native Americans, he said. After all, they were here before you were so, use their music. But he was forgetting the important thing—that Indian music has nothing to do with most of us; our forefathers were not Indians, and so their music is not our music. We didn't grow up ourselves banging on primitive drums and yelling war whoops. But Dvorak didn't worry about all that, and he got so excited that he decided to write an American symphony himself, and show us how it could be done. So he made up some Indian themes and some Negro themes (because he also decided that Negro folk music was part of American history) and he wrote a whole "New World Symphony" around those themes. But the trouble is that the Symphony doesn't sound American at all; it sounds Czech, which is what it should sound, and very pretty it is, too.

[ORCH: DVORAK: NEW WORLD SYMPHONY, 1ST MOVEMENT]

Beautiful, isn't it? But it doesn't sound American to me. Now, I'm sure you all know the second movement of the symphony—the most famous part of the symphony.

[PIANO]

A very famous tune that everybody knows by the name of "Going Home." Most people think it's a Negro spiritual, and it's often sung that way. But it isn't a Negro spiritual at all; it's a nice Czech melody by Uncle Dvorak and there's nothing Negro or American about it. In fact, if I put words to it about Czechoslovakia, it could easily sound like the Czech national anthem. Supposing I sang:

[SING: "Czech-o-slo-va-ki-a, How I long for thee. It's perfectly Czech, there's nothing American about it at all.]

But in spite of this, Dvorak made a big impression on the American composers of his time; and they all got excited too, and began to write hundreds of so-called American pieces with Indian and Negro melodies in them. It became a disease, almost an epidemic; everyone was doing it. And most of those Montezuma Operas and Minnehaha Symphonies and Cotton-Pickin' Suites are all dead and forgotten, and gathering dust in second-hand book stores. Why? Because you can't just decide to be American; you can't just sit down and say, "I'm going to write American music, if it kills me." You can't be nationalistic on purpose. That was the mistake; but it was a natural mistake for our composers to be making at the beginning; those early men were just learning to be American; they were just graduating from that Kindergarten we talked about into grammar school. But even out of this grammar school period came some pretty fine music, a lot of it by Edward MacDowell.

MacDowell wrote a suite, among other things, that uses Indian folk-stuff in it, but I still can't say that it sounds very American to me. He thought it sounded American. It's more to me like our old friend Dvorak. Just listen.

[ORCH: MACDOWELL INDIAN SUITE]

Sort of like the New World Symphony, isn't it?

Then there was a composer called Henry Gilbert, who was also very talented, but who was more interested in Negro themes than Indian ones. Here's part of a piece he wrote using tunes and rhythms of Negroes in New Orleans, especially a Creole dance called the Bamboula.

[ORCH: GILBERT: DANCE IN PLACE CONGO]

Now, as you can see, MacDowell and Gilbert and all those people wrote very fine music, indeed; but it's hard for us Americans to feel that it's our music, the way a Russian feels about a Tchaikovsky symphony. In fact, those Indian and Negro themes even sound a little strange and exotic to us if we tell the truth. So we still didn't have a real American music, not yet.

But now our American composers were about to graduate from grammar school and enter high school. By this time the First World War was already over; and something new and very special had come into American music.

[PIANO: ST. LOUIS BLUES UNDER TALK]

What was it? Can you guess what it is?

[AUDIENCE RESPONSE]

Jazz. Right! Jazz had been born, and that changed everything. Because at last there was something like an American folk music that belonged to all Americans. Jazz was everybody's music. Everybody danced the fox trot back in the twenties, everybody knew how to sing Alexander's Rag Time Band, whether he came from North Dakota or West virginia or South Carolina. So any serious composer growing up in America couldn't keep jazz out of his ears or out of his music. It was part of him, it was in the air he breathed. A composer like Aaron Copland began to write pieces such as Music for the Theatre, which is filled with jazz ideas; like this:

[ORCH: COPLAND MUSIC FOR THE THEATRE]

Imagine that being played by the Boston Symphony Orchestra for the first time thirty years ago, as it was.

What a shock the Bostonians must have had hearing Copland's jazz in Symphony Hall. But certainly, the composer who used jazz most, and most consistently was Gershwin. When he wrote his Rhapsody in Blue in 1924, he really rocked this town of New York, and finally the whole country, and then the whole civilized world. Imagine how this must have sounded to the ears of those serious concert-goers way back then.

[ORCH: GERSHWIN: RHAPSODY IN BLUE]

You see at last there was something like an American folk music that everybody understood: a real natural folk influence, jazz, much more real and natural than any Indian love calls or Negro spirituals could ever be. But, our composers were still in high school and were still being American on purpose. Only instead of Indian and Negro stuff, now they began to use jazz to be American. And just to be able to say "Look, I'm writing American music!" That wasn't very natural. But by the time we got to the thirties, in the thirties, the jazz influence became a part of their living and breathing, became a habit, and the composers didn't even have to think twice about using jazz; they just wrote music, and it came out American, all by itself. That was much better. That was leaving high school and going to college. Let's see just how this change worked. For instance, take the rhythms of jazz. The thing that makes jazz rhythm so special is something called syncopation, which means getting an accent where you don't expect one, or getting a strong beat where you expect a weak beat should be. Let's try and see if we can all do a syncopation together. We're all going to clap together, regular, even beats: 1-2-3-4, 1-2-3-4.

[ILLUSTRATES]

Fine, but without getting faster and without getting slower and just keeping it steady. And while we're doing that, keeping it steady, not rushing or slowing down, the drummers up there are going to sock their drums in a syncopated Charleston rhythm, with accents in the wrong places, in between our beats, which are the right places. O.K.? Let's see how you're going to do it.

[ORCH]

That's fine. All right. You ready? Here goes.

[ORCH & AUDIENCE]

Even and steady. Very good. No, no, no. You mustn't let them mix us up. We've got to keep steady no matter what they do so they have something to syncopate against. You understand? All right, let's try again.

[KIDS AND ORCHESTRA SYNCOPATE]

Steady, steady. Good. That's much better, much better. What we used to call the Charleston back in the twenties. Now let's turn this whole thing around and let them do the dull regular steady beat boom-boom-boom-boom, while we do the Charleston. Let's see how we're going to do it.

[KIDS SYNCOPATE AGAIN]

That's pretty good. Ready. Go! Wait a minute, wait a minute. Let them start. Now. Wonderful, wonderful. I can see you really feel those jazzy accents. And why shouldn't you? You're all American; you should feel them.

Now back in what we called the high school days, composers would use those syncopated beats just like jazz, as we heard before in the Copland piece and Gershwin piece. But in the thirties, those syncopations became a part of the music—so much so that the music doesn't even sound like jazz anymore; in other words, it was no longer using syncopation on purpose to be American, but just by accident, just by habit, so that we now get a brand new rhythm, which is an American rhythm, coming out of jazz, but that doesn't sound like jazz at all.

By now, it's become a natural part of our daily musical speech. For instance, a composer called Roger Sessions writes a piece for organ, a Chorale Prelude. Never mind what a Chorale Prelude is, but anyway just know it's a serious organ piece with a sort of religious atmosphere about it. Now that's the last place in the world where you'd expect to hear jazz and syncopated accents. But there they are, deep in the music, making it all sound very American, but without sounding anything like jazz, as you'll hear. Just listen.

[ORGAN: SESSIONS: CHORALE PRELUDE]

Now that doesn't sound like jazz at all, but it's full of jazz accents, or accents that come out of jazz, and that just couldn't be music by a European. So, it's like the English language spoken with an American accent. It's the accent that makes it almost like a whole other language. The accent, the rhythm of speaking, the speed that comes out of the way we live, the way we move in America. Just think what a difference there is between the English language spoken by a British poet like Keats, and the English language by an American poet! It's really the same language, after all; the words look the same on paper; but, boy, do they sound different! Just listen to this bit of Keats:

"Bright Star, would I were steadfast as thou artNot in lone splendour hung aloft the night,

And watching, with eternal lids apart,

And so on ... Now compare that English with this by an American poet named Kenneth Fearing:

"And wow he died as wow he lived,going whop to the office and blooie home to

sleep and

biff got married and bam had children and

off got fired,

zowie did he live and zowie did he die."

It's almost like two different languages, isn't it? Well, something like that happened to American music; the jazz influence grew to be such a deep part of our musical language that it changed the whole sound of our music.

Take a simple horn call, for example. Music has always been full of horn calls, and trumpet calls, and bugle calls. Now here's the way Beethoven used a horn call in his Third Symphony, a fine old European dignified way:

[HORN: EROICA]

And here's the way an American composer called Morton Gould uses the same notes—only they come out more like a Louis Armstrong horn-call.

[ORCH: GOULD INTERPLAY]

See what I mean? Now I don't want to give you the idea that jazz is the whole story, not by a long shot. There are many other things about American music that make it sound American besides jazz - things that have nothing to do with jazz, but have to do with the different sides of the American personality. One of the main personality traits that we have in our music is one of youth. It's young music; it's loud, strong, wildly optimistic. William Schuman is a composer who is a perfect example of this quality. His American Festival Overture, for example, is filled with rip-roaring vitality, and reminds you of kids having a marvelous time in the park. In fact, this overture was based on a street call that Schuman used when he was a kid, when the fellows used to call each other to come out and play: It's a call that went: "Wee-aw-kee!" I don't know if any of you still use that now. But in Schuman's time he did, and he based his overture on it. Listen to how he uses it.

[ORCH: SCHUMAN: AMERICAN FESTIVAL OVERTURE]

Sure has vitality, hasn't it? Nothing depressed or gloomy about old Bill Schuman.

Then there's another kind of American vitality, which is not so much of the city, but belongs more to the rugged West, full of pioneer energy. The music of Roy Harris has lots of this quality. Listen to this little bit from his Third Symphony.

[ORCH: HARRIS: THIRD SYMPHONY]

Rugged, all right. And somehow that ruggedness is purely American in its feeling.

Then there's a kind of loneliness in American music that's different from other kinds of loneliness. You find it in the way the notes are spaced out very far apart from one another, like the great wide open spaces that our big country is so full of. Take this part of Copland's ballet, Billy the Kid, for instance; this section describes a quiet night scene on the prairie.

[ORCH: COPLAND: BILLY THE KID]

Did you feel that wide-open feeling? That's very American, too.

Then there's a kind of sweet, simple, sticky sentimental quality that gets into our music; I think it comes from hymn-singing, especially from southern Baptist hymn singing. We can find lots of this kind of very American naive, plain quality in the music of Virgil Thomson, for instance, who comes from Kansas City. Here's a bit from one of his operas called The Mother of Us All, and listen for that sweet homespun American simplicity.

[ORCH: THOMSON: MOTHER OF US ALL]

You see. Then we have another kind of sentimentality in our music that comes out of our popular songs, a sort of crooning pleasure, like taking a long, delicious warm bath. Here's a part of Randall Thompson's Second Symphony—don't mix him up with Virgil Thomson— which is almost like a song Perry Como sings.

[ORCH: RANDALL THOMPSON: SECOND SYMPHONY]

In fact, there are so many different qualities in our music that it would take much too long to list them; there are as many sides to American music as there are to the American people—our great, varied, many-sided democracy. Maybe that's the main quality of all — our many-sidedness. Think of all the races and personalities from all over the globe that make up our country; and when we think of that we can understand why our own folk music is so complicated. We've taken it all in, French, Dutch, German, Scotch, Scandinavian, Italian, and all the rest, and learned it from one another, borrowed it, stolen it, cooked it all up in a melting pot. So what our composers are finally nourished on, is a folk music that is probably the richest in the world, and all of it is American, in spirit, whether its jazz, or square-dance tunes, or cowboy songs, or hillbilly music, or rock and roll, or Cuban mambas, or Mexican huapangos, or Missouri hymn-singing. It's like all those different accents we have in our speaking; there's a little Mexican accent in the Texas accents, and a little Swedish to be heard in our Minnesota accent, and there's a little Slavic in the Brooklyn, and a there's a little Irish in the Boston accent. But they're all American accents. They've been absorbed.

And now, as a final example of all this, I want you to hear part of the Third Symphony by Aaron Copland - which has a lot of these American qualities we've been talking about—jazz rhythms, and wide open optimism, and the simplicity, and the sentimentality, and a mixture of things from all over the world—a noble fanfare, a hymn—everything. But I have a special surprise for you. We've been lucky enough to get Mr. Copland himself in person to come and conduct it for you. And now you're going to meet a real American composer, who has been through this whole development we've been talking about — high school, college, even grad school — and we can say that by now he has become the dean of all American music. I am proud to turn the podium over to Aaron Copland.

[ORCH: COPLAND: THIRD SYMPHONY FINALE]

END

© 1958, Amberson Holdings LLC.

All right reserved.