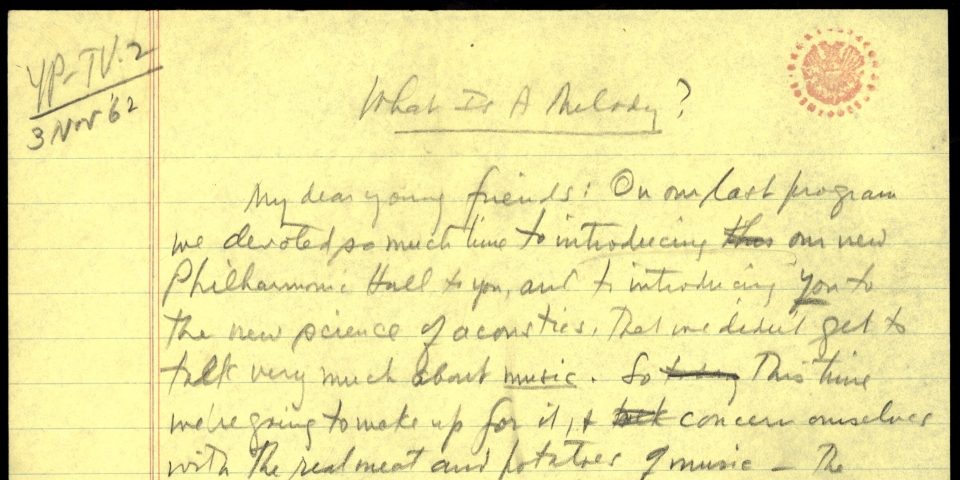

Lectures/Scripts/WritingsTelevision ScriptsYoung People's ConcertsWhat is a Melody?

Young People's Concert

What Is a Melody?

Written by Leonard Bernstein

Original CBS Television Network Broadcast Date: 21 December 1962

LEONARD BERNSTEIN:

My dear young friends: on our last program we devoted so much time to introducing our new Philharmonic Hall to you, and to introducing you to the new science of acoustics, that we didn't get to talk very much about music. So today we're going to make up for lost time, and talk about the real meat and potatoes of music -- the main course: which is melody. Now for some people music and melody are the same thing. It's the whole meal so to speak: when you think of music, you think of melody right away -- melody: music. And they're right, in a way, because what is music anyway but sounds that change and move along in time? And that's practically a definition of melody, too: a series of notes that move along in time, one after another.

Well, if that's true, then it's almost impossible to write music that doesn't have melody in it. I mean, if a melody is simply one note coming after another, how can a composer avoid writing melodies if he just writes notes. He must write melodies all the time. For example, he writes one note

then he writes another

Well, that's already a sort of melody. It's a two-note melody -sort of. Then we add another note.

Well, it's already a little more melodious, isn't it. But, if he then adds a few more

well, we've got Mendelssohn's Wedding March

See how simple it is? Where there's music, there has to be melody. You can't have one without the other.

Then why do so many people complain about music that has no melody? Some people say they don't like Bach fugues, because they don't find them melodic. And others say the same thing about Wagner operas, and others about modern music, and others about jazz. What do you suppose they mean when they say it's not melodic? What are they talking about? Isn't any string of notes a melody? Well, I think the answer is in the fact that melody can be a lot of different things: it can be a tune, or a theme, or a motive, or a long melodic line, or a bass line, or an inner voice -- all those things: and the minute we understand the difference among all those kinds of melody, then I think we'll be able to understand the whole problem. You see, people usually think of a melody as a tune, something you go out whistling, that's easy to remember, that "sticks in your mind." What's more, a tune almost never goes out of the range of the normal human singing voice - that is, too high or too low. Nor should a tune have phrases that last longer than a single normal breath in singing it. After all, melody is the singing side of music, just as rhythm is the dancing side. But the most important thing about a tune is that usually it is complete in itself -- that is, it seems to have a beginning, middle and end, and leaves you feeling satisfied -- in other words, it's a song, like Gershwin's Summertime, or Schubert's Serenade.

But in symphonic music, which is what we're mostly concerned with here, tunes aren't exactly in order, because being complete in themselves, tunes don't cry out for further development. And, as I hope you remember from former programs of ours, development is the main thing in symphonic music -- the growing of a melodic seed into a big symphonic tree. So that seed mustn't be a complete tune, but rather a melody that leaves something still to be said, to be developed -- and that kind of melody is called a theme.

Well, that's already a problem for those people who are always expecting music to have full-blown tunes, and so they'll naturally find these incomplete themes less melodic. I suppose, then, that they should complain about the famous opening four-note theme of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony:

which is hardly melodic at all. Or about this theme from his Seventh Symphony

which is mostly harping on the same note. But both of those themes are kinds of melodies, even though they're not tunes. That's the important thing to remember. They're not tunes, but they are themes. Of course, there are symphonic themes that are much more tuneful that those. Only think of Tchaikovsky's Sixth Symphony

That theme's practically a whole tune in itself.

Now what is it about that big, tuneful theme that makes it so attractive and beloved -- besides the fact that Tchaikovsky was a melodic genius? The answer is repetition -- either exact repetition, or slightly altered repetition, within the theme itself. It's that repetition that makes the melody stick in your mind; and it's the melodies that stick in your mind that are likely to please you the most. Popular songwriters know this, and that's why they repeat their phrases so often. Just think of that big song hit Mack the Knife.

Well, the same technique works just as well in symphonic themes. For instance, let's just see how Tchaikovsky went about building up that lovely theme we just heard by simply repeating his ideas in a certain arranged order -- what I like to call the 1-2-3 method. In fact, so many famous themes are formed by exactly this method that I think you ought to know about it. Here's how it works: first of all, there is a short idea, or phrase:

Second, that same phrase is repeated, but with a small variation:

That's the second part almost the same as the first. And third, the tune takes off in a flight of inspiration.

And so on, that's the 1, 2, 3 method - like a three-stage rocket, or like say the count-down in a race: on your mark, get set, go! Or in target practice: ready, aim, fire! Or in a movie studio: lights, camera, action! It's always the same, 1, 2, and then 3! There are so many examples of this melodic technique I almost don't know where to begin. But let's take, for one example, our good old stand-by, Beethoven's Fifth. One, on your mark:

two, get set:

three, go!

Or, do you know that haunting tune in the Cesar Franck Symphony? same thing. First, a phrase:

then repeat with a slight change, a rising intensity:

then the conclusion.

Or Mozart's Haffner Symphony: ready,

aim, fire!

And so on. There are millions of them, examples of this 1-2-3 design; and don't forget that the heart of the matter is repetition: 2 is always a repeat of 1, and 3 is the take-off. Now that we know a few of the secrets that make music sound melodic, let's start looking for some of the reasons why people find certain kinds of music unmelodic.

We've already discovered that what appeals most to people as melody is a fully spun-out tune, and that when they get instead an incomplete tune, or a theme, they begin to have trouble. So you can imagine that when they hear music made out of melodies that are even shorter than themes, they have even more trouble. For example, that famous 4-note opening of Beethoven's Fifth again:

-- That's so short it's not really even a theme, but what is called a motive. Now a motive can be as little as 2 notes, or 3 or 4, -- a bare melodic seed -- the raw material out of which much longer melodic lines are made. You remember I said that certain people find Wagner's operas unmelodic? This is why: because Wagner usually constructed those huge operas of his out of tiny little motives, instead of writing regular tunes such as the Italian opera composers used. But how wrong they are to say that Wagner doesn't write melody! He writes nothing but melody, only it's melody that's made out of motives. Let me show you how.

You've all heard of Wagner's great opera Tristan and Isolde and I'm sure you've heard the Prelude. Now this Prelude begins with a 4-note motive like this:

And immediately after comes another motive, also of 4 notes.

Now the exciting thing is the way Wagner puts these two motives together: he makes the second motive begin smack on the end of the first one, so that the last note of one and the first note of the other are joined, locked together, like this:

Now he adds some marvelous harmony underneath, and this is what you get, as the beginning of Tristan:

Now that's already much more than a motive, or even of two motives -- it has become what is called a phrase, just as a series of words in a language becomes a phrase. And Wagner, by using this method of joining motives together and making phrases out of them, and then paragraphs out of the sentences, finally turns out a whole story, a prelude to Tristan that is a miracle of continuous melody without end, seemingly, even though there isn't a tune anywhere in it! Do you begin to see what I mean by understanding melody in a different way? If you think you don't, just listen to a couple of minutes of this famous prelude now, and I'm sure you'll be surprised to find that you do understand it very well.

And on it goes, one long, passionate melody, for almost ten minutes. That sure is a lot of melody for a composer who is supposed to be unmelodic! But, you see, his melody grew out of little scraps, -- those motives we heard at the beginning; and that's where people make the mistake of thinking there's no melody involved.

Of course, what makes it even more difficult for people to recognize the melody is that frightening word counterpoint, which means, as you know, more than one melody going on at the same time. That really gets in people's way: but it shouldn't, because after all, the more melody the better. And counterpoint can be terribly exciting. For example, in this same Tristan prelude, much later on, Wagner builds a hair-raising climax by using counterpoint in this way: the strings are pouring out their melody, climbing higher and higher like this:

And while that frenzy is going on, the horns and cellos, down lower, are screaming out that first 4-note motive, over and over.

And that's not all. At the same time, the trumpet joins in with all his force, right in the middle, between the other two melodies, singing the second 4-note motive, again and again, like this:

Now do you think all that is too much melody for a human ear to catch all at once? Just listen and I'll bet you hear it all --every note.

Boy, what a climax that is -- one of the most thrilling ever composed. And yet it's counterpoint, that frightening word that makes some people afraid to listen to Bach fugues, or to Wagner operas. But don't you ever be scared of counterpoint; counterpoint is not an absence of melody, it's an abundance of melody; it doesn't erase melody, it multiplies it.

Now that's a lot of hard stuff we've been discussing so far; and so to make it clearer and easier for you, we're going to play you a whole movement from a Mozart Symphony, the first movement of his great G-minor Symphony, which will illustrate everything we've been talking about so far.

I'm sure you all know the beautiful theme that opens this movement. It's a perfect example of the 1-2-3 method we learned about before: first there's a phrase

and then he repeats the same phrase, slightly lower:

and, third, the take-off.

Now certainly nobody will quarrel with that as being unmelodic; it has such a beautiful shape and arch, the way it goes up and down.

That's another important feature of a good melody -- its shape -- the curve it makes, as it rises in tension, and sinks down in relaxation. And this Mozart theme is a perfectly shaped melody -- I'm sure you'll all agree with that. But in the course of the movement, as the theme is being developed, you'll find all kinds of places that might be called unmelodic, or at least less melodic. But you're ready now to understand that even those places are melodic, as much as the opening theme is -- if you just listen to them correctly. For instance, you'll notice that the very first two notes of the main theme

those two notes form a little motive by themselves, just as in Wagner, remember that motive because it is used all through the movement. About half-way along in this movement, one part of the orchestra is playing with this motive this way:

while the strings are playing in counterpoint the same 2-note motive stretched out in long notes.

you see, so that together, it makes this wonderful sound.

And that's all made out of those first two little notes that I played for you before! So you see, it's all pure melody, even the development parts. The same is true of this seemingly unmelodic section:

Some people would say that passage lacks melody; but the theme is right there, only it's down in the bass instruments here:

while on top here, there's exciting counterpoint going on, the way it goes in a Bach fugue.

You see, you just have to learn to listen for melody in the depths of music, as well as on top. Tunes aren't always on top. And if you do listen to that, how different that same passage will sound to you!

You see, what's even harder is to hear melody that's neither on top nor on the bottom, but in the middle, sort of like the middle of a sandwich. Here's one place in the movement you should be on the lookout for, where again the little 2-note motive is being developed on top, over motionless notes on the bottom like this:

But in the middle, there are two clarinets having their say about that motive like this:

And they're so sweet and tender that it would be a shame if you missed them. It would be like having two dry slices of bread with nothing in them. Now listen to the whole sandwich, top slice, bottom slice, and clarinet filling:

So all that is melody too, made out of those first two little notes of the theme.

Well, I think you're ready now to hear this great movement by Mozart, and to listen to it as melody, all of it, from start to finish, not just the themes themselves, but the development of those themes, and motives as well, with all their counterpoint. It's all melody -- every moment.

Now, the title of this program is "What is a Melody?" Well, what is it? Have we found out yet? Any series of notes we said before. But that's not a very satisfying answer because some series of notes please us and others don't. So I guess the question ought to be: "What makes an unmelody?". Well, so far we've discussed a few of the reasons why some people find certain kinds of music unmelodic -- like melodies going against each other, as in counterpoint, or a melody singing away down in the bass, not easily recognized, or buried in the middle of a sandwich, which is hard to find; or a melody constructed out of tiny motives, which is not exactly a tune. But the really important reason -- and I guess this is what I've been coming to all this time -- is the question of what our ears expect -- in other words, what we call taste. And that, in turn, is based on what our ears are used to hearing. For instance, we've seen today how important repetition is in making a melody easy to latch on to.

OK -- so what happens when we hear melodies that don't repeat at all, that just weave on and on, always new? Well, it's true that we usually like them less -- at first. But that doesn't mean they're any less melodic; in fact, the farther away you get from that kind of repetition, like Mack the Knife, the harder the melodies may get to latch on to, but also the more beautiful and nobler they can become. Some of the really greatest melodies ever written are of this kind, non-repeating long lines; only they're not necessarily the ones people go around whistling in the streets. I remember so well the day my piano teacher brought me a new piece to study when I was 14 years old, which was Bach's Italian Concerto; and when I began to read the second movement, with its long, ornamental melody line, I simply couldn't understand it. It just seemed to wander around, with no place to go. Do you know it? It goes like this:

And so it goes weaving on, spinning out that long golden thread, never once repeating itself for almost five minutes. Do you find it wandering and aimless? I find it one of the glories of all music, now today; but I sure didn't think so when I was 14; I was still young enough to think that every melody had to be a repeating tune, because that's what my brief musical experience had taught my ears to expect. In exactly the same way that our tastes change with growing up, and hearing all kinds of different music, so people's tastes change from one period of history to another. The melodies people loved in Beethoven's time would have shocked and startled the people of Bach's time, 100 years earlier, and I'm equally sure that some of today's modern music, which people complain about as ugly and unmelodic, will be perfectly charming every-day stuff to the people of tomorrow. Let us play you an example -- another long, non-repeating melodic line by the great modern German composer Paul Hindemith. Hindemith wrote this melody over 30 years ago, in a piece called Concert Music for Strings and Brass; and I suppose there are still people who call this unmelodic, even after 30 years. I consider it one of the most moving and beautifully shaped melodies, not only of modern music, but of all music; and I have a feeling that you'll agree with me after all you've learned about melody today. Just listen:

Well, whether you like that or not, now that is a great melodic line, four minutes of beautiful curves, arches, peaks and valleys, and full of emotional beauty. And if there are any of you who did not like it, who found it unmelodic, awkward, or graceless, let me comfort you by saying that those were just the exact words used 80 years ago about another German composer named Brahms.

Now these days, when we think of melody, we almost immediately think of the name Brahms; but there was a time when people complained bitterly about his music as being totally lacking in melody. And so, to wind up our program on melody, we are going to play Brahms; and to show you how careful you have to be in deciding what is a melody, and what it isn't, we are going to play for you the last movement of Brahms Fourth Symphony -- an extraordinary movement for many reasons, but chiefly for the reason that its main theme is nothing but a scale of six notes

plus two notes to finish it off. I played five notes. Six notes 1,2,3,4,5,6. Then two to finish it, which makes eight notes, eight notes in all, one to a bar. And with harmony they sound like this

And following those 8 bars come 30 variations, each one also 8 bars long, and each one containing those same 8 simple notes, always in the same key. And that, plus a short wind-up at the end, is the whole movement. Now that doesn't sound very promising in terms of melody, does it: a scale, and a cadence? And yet, what Brahms gives us in this movement is a work of such glowing fiery melodic beauty that we are left at the end cheering. How does he do it? In all the ways we talked about today: counterpoint, motives, repetition, a theme in the bass, a theme in the middle, the 1-2-3 method, remember. And I'm not going to explain it any further because I think by this time you are prepared to hear this so-called unmelodic work of Brahms as the magnificent outpouring of melody that it really is. And if you're still wondering what is melody, just listen to this movement and you'll realize that melody is exactly what a great composer wants it to be.

END

© 1962, Amberson Holdings LLC.

All rights reserved.