Latest News

Resolving the Unresolvable

Posted November 22, 2024

Resolving the Unresolvable

By Philip Clark

November 2024

Leonard Bernstein, with his librettist Stephen Wadsworth at his side, conceived his 1983 opera A Quiet Place as a sequel to Trouble in Tahiti, the one-act opera he composed in 1952. Catching up with the troubled Sam and Dinah, the married protagonists of his earlier piece, proved irresistible to Bernstein. Wadsworth, who came into Bernstein’s orbit as a friend of his daughter Jamie, turned out to be a big fan of Tahiti and proposed a follow-up that chimed with Bernstein’s own thoughts. By the end of Tahiti, Sam and Dinah had reached an uneasy truce in their marriage. Thirty years on, Dinah has been killed in a car accident, and their family, including their two children, Dede and Junior, arrive for her funeral – where tensions suppressed for years boil over.

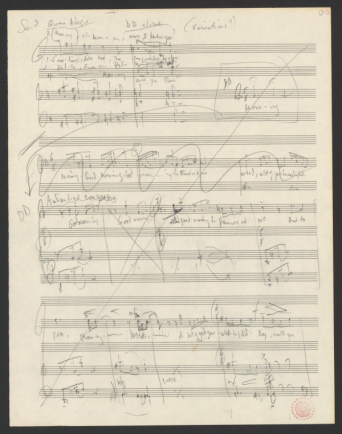

A Quiet Place, Scene 3 manuscript sketch, courtesy of the Library of Congress Music Division.

This October the Royal Opera House, London, mounted Trouble in Tahiti and A Quiet Place, using the admirably resourceful chamber versions prepared by composer Garth Edwin Sunderland. I attended midway through the run and immediately realized how skillfully Sunderland dealt with the presumed shortcomings and impracticalities of a score routinely written off as overly long, wordy, and self-indulgent.

A Quiet Place played to almost universally negative reviews when it premiered at Houston Grand Opera in the summer of 1983, a pattern that repeated itself when, two revisions later, it resurfaced at the Vienna State Opera in 1986. The recording Bernstein himself made in Vienna for Deutsche Grammophon had to wait until 2010 for reissue, and only then as part of DG’s Bernstein Music Theatre boxset, where it was cushioned by the reassuring presence of On the Town, Candide, and West Side Story. And the suspicion lingers among some critics that A Quiet Place was what happened when Bernstein abandoned the music he wanted to compose in favor of the music he felt he ought to be composing.

Reviewing the Royal Opera performance in The Guardian Flora Willson repeated the common assertion that the piece is “too atonal” while Fiona Maddocks, writing in The Observer, considered the music "a thorny, dissonant departure.” All of which raises questions about what Bernstein was attempting to achieve musically, and why people find it hard to feel the love for A Quiet Place.

A Quiet Place, The Royal Opera ©2024 Marc Brenner

Anyone expecting West Side Story 2.0 will leave the theatre disappointed: likewise anyone expecting the rootsy, pulsating funk of Mass (with prayers and thoughts for the couple sitting across from me at Covent Garden who came expecting an operatic treatment of the John Krasinski/Emily Blunt movie). The compositional task Bernstein faced was how to tease out from Trouble in Tahiti – rooted in jazz, big-band swing, Stravinsky, and Blitzstein – a new musical language appropriate for a piece set during the 1980s. At Covent Garden the two pieces ran as a double-bill: Trouble in Tahiti; interval; A Quiet Place. This had been Bernstein’s original intention. Then, under pressure to tighten the structure, the decision was taken to incorporate the earlier piece as a sequence of flashbacks inside its own sequel. Sunderland makes A Quiet Place a standalone piece again, and is the version heard on the recording conducted by Kent Nagano, released in 2018.

In truth, there is no ideal fix to the ordering. Placing Tahiti inside A Quiet Place might make for a balanced evening around an interval, but then the musical references to Tahiti in the later work appear before Tahiti itself. But to play Tahiti first is to serve dessert before A Quiet Place’s substantial main course. Sunderland’s A Quiet Place simultaneously trims and expands. Material that Bernstein cut is reincorporated, with the whole piece dispatched neatly over two digestible parts.

During the performance, two immediate thoughts came to mind. I occasionally missed the sonic weight of the Mahlerian-sized orchestra, with added electric guitar and synthesizer, that the composer had intended (although Bernstein himself had toyed with the idea of a reduced orchestration, suitable perhaps for a Broadway production). But, more importantly, I marveled at how every melodic utterance and harmonic tic was unmistakably Bernstein, as instantly recognizable as any bar of West Side Story or Candide. A thorny, dissonant departure? I think not. The final chord of Tahiti – an unsettling bitonal suppressed scream – morphs into being the first chord of A Quiet Place, an open invitation, perhaps, for future generations to move the musical material backwards and forwards through time. This pivot-chord-twixt-pieces serves a comparable function to the final chord of West Side Story: a semi-colon rather than a full stop; an aural metaphor that puts a frame around tensions that must remain necessarily unresolved. This was Bernstein, albeit with a refreshed compositional palette, doing what Bernstein did.

The metaphor of a garden was just as central to A Quiet Place, as it was to Candide. But the garden in A Quiet Place, at one time Dinah’s pride and joy, the ‘quiet place’ into which she sought haven in Tahiti, is now untended and neglected, a world away from the glittering tonal affirmation of “Make Our Garden Grow” which heralds the end of Candide. The language Bernstein deployed in A Quiet Place was appropriately knotty and overgrown, packed with atonal weeds. Tone rows were buried deep in the fabric, but the score functions tonally, albeit with tonal anchors occasionally kicked away. The nearest precedent in Bernstein’s worklist is the tussle between tonality and atonality in his 1963 Kaddish Symphony; although pouring all those musical reference points into Mass surely helped him achieve A Quiet Place. On a purely musical level the head-spinning brilliance of Bernstein’s ensemble writing made me gasp: his immaculate counterpoint carrying numerous sung points-of-view simultaneously. Symbolically I understood why Bernstein needed to push the compositional envelope so comprehensively.

Wallis Giunta (Dinah), Henry Neill (Sam) in Trouble in Tahiti, The Royal Opera ©2024 Marc Brenner

Bernstein was at a different stage of life in the early 1980s from the composer who had written Trouble in Tahiti. His wife Felicia had died; he was grappling with questions of sexuality at a time when reports were emerging of a virus, HIV, that threatened the gay community. Reviving the breezy self-confidence of his 1950s music theatre pieces would surely have felt put-on and anachronistic, and A Quiet Place was absolutely the piece he needed to write.

A Quiet Place is a vast modernist labyrinth, a churning and restless structure, impatiently on the move, broad enough to contain within it orchestral screams and jaunty blues. Bernstein recognized that he had foraged deep inside himself to create a piece-specific language – A Quiet Place, he mused, came with a “special language and sound all its own.”

--

Philip Clark is an author and journalist who has written about classical music, jazz, and rock for many leading publications, including The Wire, Gramophone, The Guardian, Prospect, and New York Review of Books. His biography of Dave Brubeck, A Life in Time, was published in 2020, and he worked with the legendary guitarist of The Kinks, Dave Davies, on his autobiography, Living on a Thin Line, published in 2022. Philip is currently writing Sound and The City—due for publication in 2026—a history of the sound of New York City. He was co-winner of the 2022 Eccles Centre and Hay Festival Writer’s Award.