Latest News

150 Years Young: A Lifelong Dialogue with Ravel

Posted February 18, 2025

150 Years Young: A Lifelong Dialogue with Ravel

by Michael Stephen Brown

Maurice Ravel, 1925. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

When I was thirteen, I labored over the first phrase of Ravel’s Sonatine, balancing the voicing and crafting its crystalline texture. It wasn’t just about playing it correctly—it was about sculpting sound from a block of ice. The pedal and touch had to be just right, as if I were holding something fragile. I had never encountered a sound world like this before—where two hands could unlock an endless range of textures, colors, and emotions. Ravel’s piano music introduced me to an evocative new language and remains a constant companion to which I am drawn again and again.

Decades earlier, Leonard Bernstein, another hero of mine, had a similarly transformative encounter with Ravel. At the age of fourteen, he attended his first orchestral concert in 1932—a performance by the Boston Pops that concluded with Boléro. Reflecting on that moment, Bernstein exclaimed, “I had never experienced anything like this in my life! That piece of orchestration is like the bible of orchestrators” (Burton, Leonard Bernstein). Bernstein’s immersion in Ravel’s music began early. As a student at the Curtis Institute, he performed the Prélude and Rigaudon from Le Tombeau de Couperin. These piano works gave Bernstein an insider’s tactile knowledge of Ravel’s intricate piano writing, which, combined with his love for Ravel’s orchestration, infused his interpretation of the Concerto in G with kinetic energy and vibrant expression.

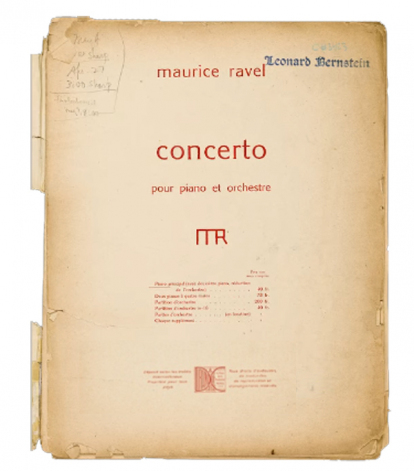

Browse Leonard Bernstein's score at the New York Philharmonic's Shelby White & Leon Levy Digital Archives.

In that iconic concerto, one of my desert-island pieces, Bernstein transcends the challenge—he doesn’t just perform the music; he becomes it, as if he were the composer himself. His journey with the piece began in 1937, at the age of nineteen, when he played it during his professional debut as a pianist with the State Symphony Orchestra in Cambridge. Throughout his career, he performed it countless times, often as both pianist and conductor. It became one of his signature pieces, revisited, deepened, and molded time and time again.

Watching Bernstein play and conduct the Concerto with the Orchestre National de France from 1975 (a video I’ve probably seen a hundred times), I feel as if he’s communing directly with the music’s soul. His music-making blends youthful enthusiasm with the wisdom of a master, infused with such joy that one can’t help but want to experience it over and over. It’s rare for a recording to feel alive, as if you are there with the performer, but Bernstein invites you to join his celebration. Each phrase feels like a fresh discovery, and the second movement, where the piano sings alone for nearly three minutes, exists on a whole other plane of human experience. Ravel once said of that flowing phrase, “It nearly killed me!” Bernstein channels that struggle, milking each interval for its expressive potential, making them sing. When I hear him play the finale, my heart rate skyrockets; I can’t help but jump out of my chair. I often find myself wondering: did Ravel or Bernstein write this piece?

Bernstein’s influence lingers every time I revisit the Concerto. I often ask myself: How much of his approach should guide mine, and how much should I carve my own path? The truth is, having Bernstein in my thoughts doesn’t constrain me; it frees me. His fearless connection to the music gives me permission to find my own voice within Ravel’s world. I engage in a living conversation—not just with the orchestra, but with Bernstein, with Ravel, with every performer who’s ever touched this piece.

Perhaps this is why I’m compelled to write, 150 years after Ravel’s birth. His music speaks a language uniquely his own, a language that demands years of devotion. You can hear this vividly in Bernstein’s rehearsal from that same Concerto performance in France, where he vocalizes the musical gestures, as if the music itself were a language he’s fluent in. Every nuance is exact in his mouth, his voice rising and falling, passionately shouting in French. It’s fantastic! Performers like Bernstein speak the language of Ravel, infusing each note with their own breath, their own spirit. Ravel’s music is at once precise and mysterious, but it’s the performer who ignites that mystery, transforming it from written notes into an experience that is felt, rather than just heard.

This truth is made clear every time I sit at the piano. There’s one composer, without fail, who stops my partner Angeline in her tracks—Ravel. His works are often a welcome relief, as she humorously reminds me, from the weight of the Hammerklavier fugue. Through her eyes, I find myself revisiting Ravel’s music with fresh wonder, whether it’s the Sonatine, Miroirs, Valses nobles et sentimentales, or even the subtle Menuet sur le nom d'Haydn. Each piece carries Ravel’s signature sound—both personal and expansive—just as Bernstein once called it: “the Bible of orchestrators.” His music speaks with a voice that is both intimate and boundless, a rare gift for any composer.

I love imagining how performers like Bernstein confront the challenges a composer leaves on the page, and the creative solutions they discover. It’s comforting to know that, as performers, we all face the same insurmountable mountain. This is the role of the performer—not just to translate the notes, but to bridge the composer’s world with the listener’s heart. To define not just how the piece sounds, but what it means in our time. Ravel gives us the architecture; performers like Bernstein give it life. And as I return to that glistening phrase in the Sonatine, I realize that with every performance, every touch, every new encounter, the music is like ice under a sculptor’s chisel—shaping itself, catching the light, and dancing into forms I never dreamed possible.

Works Cited: Burton, Humphrey. Leonard Bernstein. Doubleday, 1994.

Michael Stephen Brown is a composer and pianist currently in residence at MacDowell. His works have been commissioned by various ensembles, and he regularly performs worldwide. www.michaelbrownmusic.com