Latest News

Close Encounters with Arias and Barcarolles

Posted February 13, 2026

Close Encounters with Arias and Barcarolles

by Steven Blier

In the spring of 1989 I received a call from Michael Barrett, who had founded a concert series with me that past fall—New York Festival of Song, soon to be known by its acronym, NYFOS. Michael had an interesting piece of news: the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, now with a new artistic director, had decided not to program the piece they had previously commissioned from Leonard Bernstein, and we were in line to snag the US premiere of the work’s definitive version. It was called Arias and Barcarolles, inspired by a gnomic comment Dwight D. Eisenhower made to Bernstein after a concert in the White House. Of all the pieces he'd heard that afternoon, he said, he liked Rhapsody in Blue best because it had “a theme, not like all them arias and barcarolles.”

Photo: Leonard Bernstein, President Eisenhower, Leonard Warren, and Rise Stevens at the Lincoln Center ground-breaking ceremony, May 14, 1959. New York Times, courtesy of the NY Phil Shelby White & Leon Levy Digital Archives

A’s and B’s (as it has come to be called) covers the waterfront musically; ironically enough, the only two thingsit seems to lack are an aria or a barcarolle. The piece is a virtuoso display of twentieth century musical styles: from Coplandesque lyricism, to the energetic wit of Stephen Sondheim, to fractured minimalism, to atonality in three completely different styles. It turned out to be Leonard Bernstein’s final vocal work, and it did not reveal its secrets very quickly to me.

I learned A’s and B’s from a Xerox of the manuscript, which under the best of circumstances is a challenge. Bernstein’s score is cleaner than many, and it can be inspiring to come face-to-face with the very pen-stroke that transmitted the composer’s inspiration to the page. In a piece as unpredictable as this one, though, I would have welcomed the cool, neutral comfort of an engraved score. I had good days and bad days as I committed the notes to my brain.

I had a not-so-secret weapon. Michael Barrett, Co-Director and -Founder of NYFOS, had been in close artistic proximity to the piece as it was being written. He had actually played it with the Maestro himself, and he knew every nuance, every beat, every tempo. Michael was not only the best guide possible to the intricacies of A’s and B’s, but also the most patient. I found the piece daunting, and I remember one day when I had a total meltdown. Michael coddled me through it.

After we were granted the rights to premiere the definitive version of A’s and B’s in New York, we had to find a hall, a date—and, most importantly, a cast. Since the score demands theatrical savvy, the musicianship to master the challenges of gnarly vocal lines, and the ability to sing American English with clarity and naturalness, the field was limited. We asked Judy Kaye, fresh from winning a Tony Award for Phantom, and William Sharp, whose debut album of American art songs had been nominated for a Grammy. On the face of it, they were an odd couple: Judy was a Broadway baby, while Bill was known for Lieder and early music. But the Venn diagram of their gifts turned out to have more overlap than met the eye. Judy’s enviable vocal technique allowed her to sing a few opera roles, and Bill had a subtle but infallible instinct for comic timing and all-out drama.

Photo: Michael Barrett, Leonard Bernstein, Steven Blier, baritone William Sharp, and soprano Judy Kaye preparing Arias & Barcarolles, 1989.

The performance, at Merkin Hall on September 7, 1989, was a success with the audience, and propelled our scruffy, grassroots concert series into the limelight. True, A’s and B’s puzzled the critics on first hearing. “I’m not sure what to make of it all,” wrote Andrew Porter in the New Yorker. In those days, it was fashionable to take pot-shots at Bernstein. He’d had a couple of well-publicized misfires (1600 Pennsylvania Avenue on Broadway, A Quiet Place in the opera house) and it looked to some as if his creative judgment had derailed. When we offered the work to four independent record labels, we were turned down by all of them.

Admittedly, Arias and Barcarolles does take time to understand. Even after several performances, I didn’t completely grasp its true meaning. But when I had to provide program notes for the premiere recording (yes, a brand-new label, Koch International, led by producer Michael Fine, swept in and led us straight to a Grammy Award), I finally saw A’s and B’s for what it was: Bernstein’s valedictory portrait of himself and his family. Everything is there: his tangled love affairs (“Prelude,” “The Love of My Life”); the complex détente of his marriage (“Love Duet,” “Mr. and Mrs. Webb Say Goodnight”), his mother (“Little Smary”), his children (“Greeting”), his departed friends (“Nachspiel”), and most significantly, his musical genius that was so explosive, so erotic, that it could merge Eros and Thanatos—love and death—in a crucible of terrifying power (“Oif Mayn Ches’neh”).

In the final decades of his creative life, Bernstein wanted to grapple with the great issues of American life. But for this final piece, he turned his gaze inward, giving us an intimate, honest portrait of his psyche with all its conflicts, regrets, joys, conundrums, and passions. In Arias and Barcarolles, Bernstein exorcises his demons. It is a work whose rich complexity stands with his finest.

--

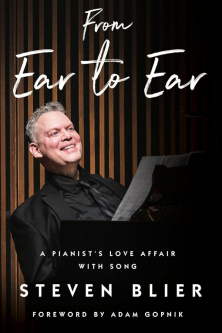

Steven Blier is the author of the new memoir, From Ear to Ear. He is on the faculty of the Juilliard School, and heads New York Festival of Song, now in its fourth decade.

More information about Arias and Barcarolles can be found in Steven Blier's new book, From Ear to Ear. MORE INFO