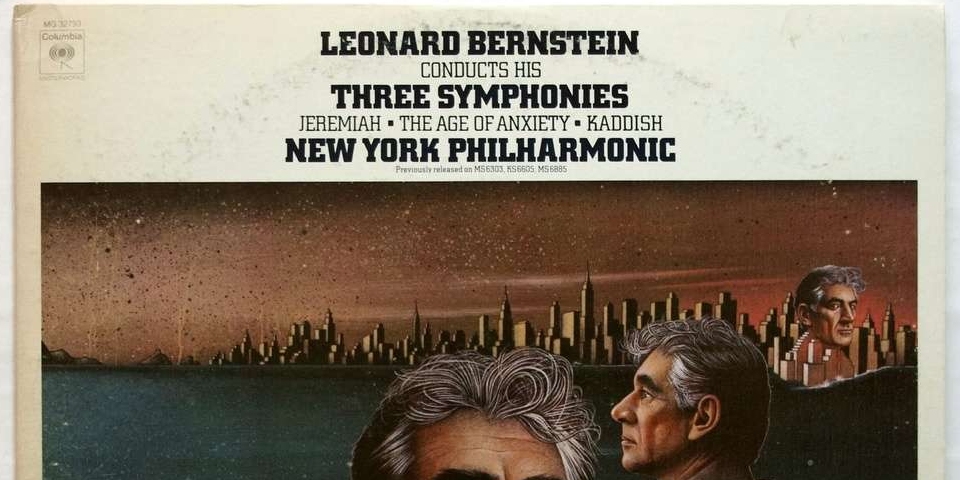

Works Chorus & Orchestra Symphony No. 3: Kaddish (1963)

Background

by Jack Gottlieb

To the Jews of the world, the word Kaddish ("Sanctification") has a highly emotional connotation, for it is the name of the prayer chanted for the dead, at the graveside, on memorial occasions and, in fact, at all synagogue services. Yet, strangely enough, there is not a single mention of death in the entire prayer. On the contrary, it uses the word chayei or chayim ("life") three times. Far from being a threnody, the Kaddish is a series of paeans in praise of God, and, as such, it has basic functions in the liturgy that have nothing to do with mourning.

This doxology (the first two sections) is written in a mixture of Hebrew and Aramaic, the vernacular language at the time of Jesus. In fact, there is reason to believe that the doxology became the basis for the Christian Paternoster (Lord's Prayer). Originally, in the period following the destruction of the Second Temple (70 A.D.), fragments of the Kaddish recited by a preacher at the end of an discourse when he was expected to dismiss an assembly with an allusion to the Messianic hope. It was not until the 12th century, however, that the prayer reached it's present-day form, and through folklore came to be associated with mourning.

In his Kaddish Symphony, Leonard Bernstein exploits the dualistic overtones of the prayer: its popular connotation as a kind of requiem, and its celebration of life ( i.e. creation). He does this both in his speaker's text and in his music. In the original version, the choice of a woman as the Speaker and as vocal soloist (singing sacred words traditionally reserved for men in the synagogue) was in itself a dualistic decision. The woman represented in the Symphony, that aspect of humankind which know God through intuition, and can come closest to Divinity, a concept at odds with the male principal of organized rationality. (Bernstein used the same device thirty-six years ago in his Symphony No. 1, Jeremiah, in which the Prophet's Lamentation is sung by a mezzo-soprano.

Because he was not satisfied with the original (1963) version, the composer, in 1977, made some revisions. These included a few cuts, some musical re-writing and even more re-writing of the spoken text. Furthermore, he made it possible for the speaker to be either a woman or a man.

But the dualism is more than a matter of which gender is the narrator. The Speaker mourns, in advance, humanity's possible imminent suicide. At the same time, it is observed that people cannot destroy themselves as long as they identify themselves with God. Hence, human beings as creators, as artists, as dreamers (as, therefore divine manifestations), could be immortal.

Musically, this dualism is illustrated by the dramatic contrast between intensely chromatic textures (which employ twelve-tone techniques) and simple expressive diatonicism. For example, there is a particularly anguished outburst by the Speaker in the middle of the Din-Torah (trial-scene or "Judgement by Law") in which God is accused of a breach of faith with humanity.

Such "blasphemy" has a Biblical precedent in the story of Job and also has its roots in the folk traditions, as in the legend of Rabbi Levi Yitzhok of Berditchev. Bernstein strongly felt the peculiar Jewishness of this "I-Thou" relationship in the whole mythic concept of the Jew's love of God, from Moses to the Hasidic sect, there is a deep personal intimacy that allows things to be said to God that are almost inconceivable in another religion.

This change is manifested by agonized, non-tonal music which culminates in an eight-part choral cadenza of vast complexity. But immediately after this, the Speaker begs God's forgiveness and tries to be comforting; and the ensuing lullaby is explicitly tonal, with gentle modulations.

Again, at the climax of the Symphony (in the Scherzo), another painful spoken moment, musicalized in extreme, angular motives, is followed by a gradual clarification and resolution into G-flat major. The critical word of the Speaker at this point is "believe". Indeed, the composer's credo resided in his belief in the enduring value of tonality.

Text

Revised Speaker's text by Leonard Bernstein

Movement I

INVOCATION

SPEAKER

O, my Father: ancient, hallowed,

Lonely, disappointed Father:

Betrayed and rejected Ruler of the Universe:

Angry, wrinkled Old Majesty:

I want to pray.

I want to say Kaddish.

My own Kaddish. There may be

No one to say it after me.

I have so little time, as You well know.

Is my end a minute away? An hour?

Is there even time to consider the question?

It could be here, while we are singing.

That we may be stopped, once for all,

Cut off in the act of praising You.

But while I have breath, however brief,

I will sing this final Kaddish for You,

For me, and for all these I love

Here in this sacred house.

I want to pray, and time is short.

Yit'gadal v'yit'kadash sh'mē raba ...

KADDISH 1

SPEAKER

MAGNIFIED ... AND SANCTIFIED ...

BE THE GREAT NAME ... AMEN.

CHORUS

Yit'gadal v'yit'kadash sh'mē raba, amen

b'al'ma div'ra chir'utē,

v'yam'lich mal'chutē

b'chayēchon uv'yomēchon

uv'chayē d'chol bēt Yis'raēl,

ba'agala uviz'man kariv,

v'im'ru: amen.

Y'hē sh'mē raba m'varach

l'alam ul'al'mē al'maya.

Yit'barach v'yish'tabach v'yit'pa-ar

v'yit'romam v'yit'nasē

v'yit'hadar v'yit'aleh v'yit'halal

sh'mē d'kud'sha, b'rich Hu,

l'ēla min kol bir'chata

v'shirata, tush'b'chata v'nechemata,

da-amiran b'al'ma,

v'im'ru: amen.

Y'hē sh'lama raba

min sh'maya v'chayim alēnu

v'al kol Yis'raēl

v'im'ru: amen.

Translation

(Magnified and sanctified be His great name, Amen

Throughout the world which He hath created

according to His will;

And may He establish His kingdom

During Your life and during Your days,

And during the life of all the house of Israel,

Speedily, and at a near time,

And say ye, Amen.

May His great name be blessed,

Forever and to all eternity.

Blessed and praised and glorified,

And exalted and extolled and honored,

And magnified and lauded

Be the name of the Holy One, blessed be He;

Though He be beyond all blessings,

And hymns, praises and consolations,

That can be uttered in the world.

And say ye, Amen.

May there be abundant peace

From heaven, and life for us

And for Israel;

And say ye, Amen.)

SPEAKER Amen! Amen! Did You hear that, Father?

"Sh'lama raba! May abundant peace

Descend on us. Amen."

Great God,

You make peace in the high places,

Who commanded the morning since the days began,

And caused the dawn to know its place.

Surely You can cause and command

A touch of order here below,

On this one, dazed speck.

And let us say again: Amen.

CHORUS

Oseh shalom bim'romav,

Hu ya-aseh shalom alēnu

v'al kol Yis'raēl

v'im'ru: amen.

(He who maketh peace in His high places,

May He make peace for us

And for all Israel;

And say ye, Amen)

Movement II

DIN TORAH

SPEAKER

With Amen on my lips, I approach

Your presence, Father. Not with fear,

But with a certain respectful fury.

Do You not recognize my voice?

I am that part of Man You made

To suggest his immortality.

You surely remember, Father?—the part

That refuses death, that insists on You,

Divines Your voice, guesses Your grace.

And always You have heard my voice,

And always You have answered me

With a rainbow, a raven, a plague, something.

But now I see nothing. This time You show me

Nothing at all.

Are You listening, Father? You know who I am:

Your image; that stubborn reflection of You

That Man has shattered, extinguished, banished.

And now he runs free—free to play

With his new-found fire, avid for death,

Voluptuous, complete and final death.

Lord God of Hosts, I call You to account!

You let this happen, Lord of Hosts!

You with Your manna, Your pillar of fire!

You ask for faith, where is Your own?

Why have You taken away Your rainbow,

That pretty bow You tied round Your finger

To remind You never to forget Your promise?

"For lo, I do set my bow in the cloud ...

And I will look upon it, that I

May remember my everlasting covenant ..."

Your covenant! Your bargain with Man!

Tin God! Your bargain is tin!

It crumples in my hand!

And where is faith now—Yours or mine?

CHORUS (Cadenza)

Amen, Amen, Amen ...

SPEAKER

Forgive me, Father. I was mad with fever.

Have I hurt You? Forgive me,

I forgot You too are vulnerable.

But Yours was the first mistake, creating

Man in Your own image, tender,

Fallible. Dear God, how You must suffer,

So far away, ruefully eyeing

Your two-footed handiwork—frail, foolish,

Mortal.

My sorrowful Father,

If I could comfort You, hold You against me,

Rock You and rock You into sleep.

KADDISH 2

SOPRANO SOLO AND BOYS' CHOIR

Yit'gadal v'yit'kadash sh'mē raba, amen ...

SPEAKER

Rest, my Father. Sleep, dream.

Let me invent Your dream, dream it

With You, as gently as I can.

And perhaps in dreaming, I can help You

Recreate Your image, and love him again.

Movement III

SCHERZO

SPEAKER

I'll take You to Your favorite star.

A world most worthy of Your creation.

And hand in hand we'll watch in wonder

The workings of perfectedness.

This is Your Kingdom of Heaven, Father,

Just as You planned it.

Every immortal cliché intact.

Lambs frisk. Wheat ripples.

Sunbeams dance. Something is wrong.

The light: flat. The air: sterile.

Do You know what is wrong? There is nothing

to dream.

Nowhere to go. Nothing to know.

And these, the creatures of Your Kingdom,

These smiling, serene and painless people—

Are they, too, created in Your image?

You are serenity, but rage

As well. I know. I have borne it.

You are hope, but also regret.

I know. You have regretted me.

But not these—the perfected ones:

They are beyond regret, or hope.

They do not exist, Father, not even

In the light-years of our dream.

Now let me show You a dream to remember!

Come back with me, to the Star of Regret:

Come back, Father, where dreaming is real,

And pain is possible—so possible

You will have to believe it. And in pain

You will recognize Your image at last.

Now behold my Kingdom of Earth!

Real-life marvels! Genuine wonders!

Dazzling miracles! ...

Look, a Burning Bush!

Look, a Fiery Wheel!

A Ram! A Rock! Shall I smite it? There!

It gushes! It gushes! And I did it!

I am creating this dream! Now

Will You believe?

I have You, Father, locked in my dream,

And You must remain till the final scene ...

Now! Look up! High! What do You see?

A rainbow, which I have created for You!

My promise, my covenant!

Look at it, Father: Believe! Believe!

Look at my rainbow and say after me:

MAGNIFIED ... AND SANCTIFIED ...

BE THE GREAT NAME OF MAN!

The colors of my rainbow are blinding, Father,

And they hurt Your eyes, I know.

But don't close them now. Don't turn away.

Look. Do You see how simple and peaceful

It all becomes, once You believe?

Believe!

Believe!

KADDISH 3

BOYS' CHOIR

Yit'gadal v'yit'kadash sh'mē raba, amen.

SPEAKER

Don't waken yet! However great Your pain,

I will help You suffer it.

O God, believe. Believe in me

And You shall see the Kingdom of Heaven

On Earth, just as You planned.

Believe ... believe.

See how my rainbow lights the scene.

The voices of Your children call

From corner to corner, chanting Your praises.

BOYS' CHOIR

b'al'ma div'ra chirut? ...

SPEAKER

The rainbow is fading. Our dream is over.

We must wake up now, and the dawn is chilly.

FINALE

SPEAKER

The dawn is chilly, but the dawn has come.

Father, we've won another day.

We have dreamed our Kaddish, and wakened alive.

Good morning, Father. We can still be immortal,

You and I, bound by our rainbow.

That is our covenant, and to honor it

Is our honor ... not quite the covenant

We bargained for, so long ago,

At the time of that Other, First Rainbow.

But then I was only Your helpless infant,

Arms hard around You, dead without You.

We have both grown older, You and I.

And I am not sad, and You must not be sad.

Unfurrow Your brow, look tenderly again

At me, at us, at all these children

Of God here in this sacred house.

And we shall look tenderly back to You.

O my Father, Lord of Light!

Beloved Majesty: my Image, my Self!

We are one, after all, You and I:

Together we suffer, together exist,

And forever will recreate each other.

Recreate, recreate each other!

Suffer, and recreate each other!

SOPRANO SOLO, BOYS' CHOIR, AND CHORUS

Y'hē sh'mē raba m'varach ...

Comments from Leonard Bernstein

What is a father in the eyes of a child? The child feels: My father is first of all my Authority, with power to dispense approval or punishment. He is secondly my Protector; thirdly my Provider; beyond that he is Healer, Comforter, Law-giver, because he caused me to exist. And as the child grows up he retains all his life, in some deep, deep part of him, the stamp of that father-image whenever he thinks of God, of good and evil, or retribution. For example, take the idea of defiance. Every son, at one point or other defies his father, fights him, departs form him, only to return to him - if he is lucky - closer and more secure than before. Again we see clearly the parallel with God: Moses protesting to God, arguing, fighting to change God's mind. So the child defies the father and something of that defiance also remains throughout his life. (HB claims these words represent LB's thinking aloud about Kaddish which he was composing at the time)

[Tribute to Samuel J. Bernstein. August 1961 in HB pg. 326- 327]

On August 1st, I made the great decision to go forward with Kaddish, to try and finish it, score it, rehearse, prepare, revise, translate into Hebrew...It's a monstrous task: I've been copying it out legibly for the copyists, night and day and now it's ready, except for a rather copious finale that remains to be written.. I'm terribly excited about the new piece, even about the Speaker's text, which I finally decided has to be done by me. Collaboration with a poet is impossible on so personal a work, so I've found after a distressful year of trying with Lowell and Seidel; so I'm elected, poet or no poet. But the reactions of various people to whom I've read it have been so moving (and moved) that I was encouraged to keep at it. I think you'll be surprised by its power.

[Letter to Shirley Bernstein, August 10, 1963 in HB pg. 336]

It's been an unbelievable experience - we are all exhausted

[Letter to Helen Coates. After Kaddish premier, Tel Aviv, Dec. 13, 1963]

FANTASTIC SUCCESS WITH PUBLIC AND PRESS DESPITE SHAKY FIRST PERFORMANCE. STOP SPREAD THE WORD

[Letter to Helen Coates. Cable re: Kaddish premier, Tel Aviv, Dec. 11, 1963]

I think the Psalms are like an infantile version of Kaddish, if you know what I mean. They are very simple, very tonal, very direct, almost babyish in some ways and therefore it stands perilously on the brink of being sentimental if wrongly performed."

[Interview with J. Goldsmith, R.A. Hall, and R. Allen re: symphonies, for Columbia Records Convention, Aug. 3, 1965]

I love Kaddish - I think it's a beautiful work but I'm not at all satisfied with the text. And God knows I tried everything not to write it myself.... I worked with Cal Lowell. And he actually wrote 3 poems for it. He wrote 3 very beautiful poems but they're you know, lyric poems of a certain obscurity which would not have served the purpose of immediacy which was needed in the concert hall with a piece like that. That immediately communicates with the audience. They were too literary and he realized it too.... After having written these 3 beautiful poems, he said I'm not the man for you and I have a young disciple, a friend named Freddy Siedell who is absolutely perfect for this.

And so he put me and Siedel together and we worked for months and Siedel works like at the rate of one word a week. Very very slow and what was coming out was so little in the first place that I knew it would never get done in time for the performance that fall. And also I wasn't crazy about what was coming out. I didn't like the images and it was all full of black saxophones - it just - it sounded wrong and old fashioned in another way. Finally I had to do it myself. And I worked very very hard. And some of it is good. Some of it is much better than has been said by very angry critics. I've never seen criticisms such as Kaddish had.

[Intv. w/ John Gruen, Ansedonia Italy, 1967. Tape # 11, side A pg. 1 - 8]

In my fervor to make it [Kaddish] immediately communicative to the audience, I made it over communicative. So that.. there are embarrassing moments. Even I am embarrassed when I hear the record here and there. And I know Felicia had moments which I changed which she just couldn't say. They were so over verbose and I did enormous cutting. But it's still too much and it's still too corny is the only word I can find. And I do wish I could revise it or find somebody who could revise it well and cut it down.

[Intv. w/ John Gruen, Ansedonia Italy, 1967. Tape # 11, side A pg. 1 - 8]

Obviously [the biblical thing interested me]. I mean I keep coming back to it. I've written 2 works in the last 10 years, can you imagine since I took the Philharmonic which was at the point when I finished West Side Story. Since then I've written 2 works, neither of them for the theater in all that time. And one was Kaddish and one is the Chichester Psalms - they're both biblical in a way. So obviously something keeps making me go back to that book.

[Intv. w/ John Gruen, Ansedonia Italy, 1967. Tape # 11, side A pg. 1 - 8]

[The reason for the new version of the Kaddish Symphony is] because I wasn't satisfied with the old version. There was too much talk... The piece is essentially the same except better. It is tighter, shorter, there are cuts, there is some musical re-writing and a lot of re-writing of the spoken text. [The speaker is also now a man but] I did not change from a woman to a man. I changed so that it could be either... The original idea was that it was a woman because it was 'das ewig Weibliche'. It was that part of man that intuits God - you see what I mean? And then I realized that that was too limiting. So I made it for either.

[Berlin Press Conference, September 12, 1977]

But Kaddish is the most extended 12-tone writing of any piece I have ever done.

[Berlin Press Conference, September 12, 1977]

The most striking example of [my writing 12 tone music] is Kaddish - my third symphony. It contains a great deal of highly complex carefully worked out [music] according to the Schoenbergian system, twelve tone music. As a matter of fact I remember when it was first played in Boston, the American premier of the symphony with Charles Munch conducting. A whole group of young composers who were at the time considering themselves very avant-garde artists, who had gotten wind of the fact that I had finally written a twelve tone piece, came to all of the rehearsals in a body. Arthur Berger, Harold Shapero, Leon Kirschner, the Harvard group, the Brandeis group, and they were all terribly excited until about the midpoint of the symphony when the second Kaddish, which is sung by a soprano and which is a lullaby and completely tonal, appeared, and they all threw up their hands in despair and said, oh, well, there it goes. That's the end of that piece......... Of course they didn't understand at all that one of the main points of the piece is that the agony expressed with the twelve tone music has to give way -- this is part of the form of the piece -- to tonality and diatonicism even so that what triumphs in the end, the affirmation of faith is tonal.

[Intv. w/ Peter Rosen, 1977. Reflections pg 52 - 57]

I find the word eclectic has been grossly misconceived and misused. Now, in the case of Kaddish there was a real point - which I didn't decide on deliberately because as I say I don't make stylistic decisions but it came out quite unconsciously and the way all art comes out unconsciously and it's only after the unconscious period that the conscious mind takes over and makes a form, puts it all into viable shapes. During [the] period of writing Kaddish it was, it's obvious to me now that at that point the tremendous agony of the dialogue with God which occupies the main portion of Kaddish had to be expressed in the expressionistic and well Schoenbergian if you like, or Bergen manner. And as the piece went through its agony towards its climax and then its gradual resolution into a reaffirmation of another kind of faith it became increasingly diatonic and it isn't just that the music became more diatonic, it's that the same music which was twelve tone evolved slowly, very, very gradually into diatonic music, but it was always the same piece. And this I know only by looking back it and having an objective view of the piece so that I can analyze it as a musicologist would.

[Intv. w/ Peter Rosen, 1977. Reflections pg 52 - 57]

There was a period, that was of course, during '62 and '63 that I was writing that piece while I was still music director of the Philharmonic, and as I was finishing the final amens of the jubilant fugue which concludes the piece, the news came of the assassination of Jack Kennedy which threw me for a loop..... At that moment, I realized that I had to dedicate the piece to the beloved memory of this man whom I did indeed love very much. .... This brings up the whole problem of what music had to do with current affairs, with politics, with whatever, and it really has little if anything to do except as a great time capsule -- an artistic incarnation of a given period in history.

[Intv. w/ Peter Rosen, 1977. Reflections pg 52 - 57]

I have very good luck with my colleagues, they are all so wonderful. Miss Hendricks, my soprano in Kaddish, I think was born to sing that note, that line. It is so fine and sensitive. She has all the breaths under control to sing that very difficult lullaby, and Michael Wager who does the speaking which is no small job. It's a much bigger job than Miss Hendricks because he never stops, he never shuts up. He is, I suppose, my voice and he has a tremendous argument with God, which many people find too strong or maybe even blasphemous. But which is in the old Judaistic tradition. I mean all our great Judaistic personalities of the past including Abraham who founded Judaism, and Moses and the prophets all argued with God. They argued with God the way you argue with somebody who's so close to you that you love so much, that you can really fight. You know how the more you love someone the more you can get angry with them and when you have a reconciliation, the more close you become than ever. Something like that happens in the course of this piece and it takes a really extraordinary actor to be able to perform that.

[Intv. w/ NHK TV, Hiroshima Peace Journey, 1985 TC. 24:20]

[I wrote the libretto myself as well as composing the piece]. That's what I mean by the speaker representing my voice. I originally wrote it to be spoken by my wife and I wrote it for a woman although women are not officially supposed to say Kaddish in the old tradition.... Only the man stood up and said Kaddish for his dead father and mother but that's one old tradition I didn't stick to.

[Intv. w/ NHK TV, Hiroshima Peace Journey, 1985 TC. 24:20]

I wrote it for [a woman] because the essence of the speaker was the female side of all persons male or female. We all have this female side that is more intuitive and not so reliant on logical thought process, but I'm not saying that that's inferior in any way. ..... So I wrote it for that side of man, the female side, which guesses God's grace and hears his voice, not the way Jeremiah or the great prophets .. the voice inside.

I wrote it for [Felicia] because I love her and also because she was a very great actress and I have even much more outspokenly feminine roles at the time. She compares herself in the text with the Rose of Sharon, the Lily of the Valley, quotes from the Song of Songs from the Bible and there were many references to her femininity.

Which have now been taken out since she died. I could not find a woman that could ever replace her because she was unique. More than that I cannot say, she was one person in the history of the world - that was Felicia. I would never let another actress do it so I changed it, I revised it to be a man and Michael Wager, who has always been very close to our family and had a particularly close relationship with Felicia, took over the role. I took out the female references only - not all. I took out the out-spoken obvious, evidence regarding this like the Rose of Sharon. But I left in, he says: 'I am that part of man -- you may, who guesses your grace.' That's the female side

[Intv. w/ NHK TV, Hiroshima Peace Journey, 1985 TC. 24:20]

I'm proud of [the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra] and close to them and spiritually somehow akin, whether we play Mozart or my own Kaddish Symphony (the best performance of Kaddish I've ever heard).....

[Harvard's 350th Anniversary Dinner Speech October 10, 1986]

[The speaker] represents Man, or that part of Man God made to suggest his immortality.. the part that refuses death, that insists on God.

[Intv. (?) 1987 in Gradenwitz, pg. 159]

LB100

Throughout the Leonard Bernstein Centennial, Bernstein’s three symphonies saw a particularly noteworthy increase in performances, with Symphony No. 3: Kaddish receiving 54 performances by 28 orchestras, featuring 17 narrators and 17 sopranos, across Asia, Europe, and North America. Leading orchestras that championed all three symphonies during the Centennial include the New York Philharmonic, Shanghai Symphony Orchestra, Real Orquesta Sinfonica de Sevilla, and Orchestra dell'Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia. The latter’s recording of the symphonies under the baton of Antonio Pappano garnered critical acclaim.

Related Works

Symphony No. 1: Jeremiah

Symphony No. 2: The Age of Anxiety

Chichester Psalms

Details

Canon in Five Parts from Symphony No. 3: Kaddish

(1963) 1 min

for five-part boy choir with keyboard accompaniment

World Premiere: December 18, 1979 | Brick Presbyterian Church, New York, NY, United States / Maala Roos, conductor

To perform Symphony No. 3: Kaddish, please contact Boosey & Hawkes. For general licensing inquiries, click here.

To purchase sheet music for Symphony No. 3, Kaddish, please visit our store.

Media

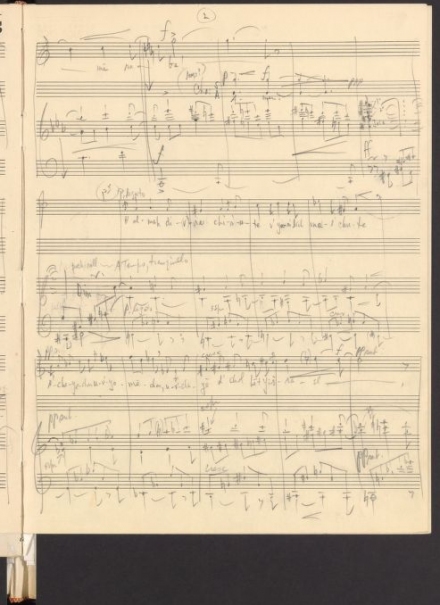

Kaddish (sketch score)

Library of Congress Digital Archives

Library of Congress Digital Archives

Centennial Kaddish Narrators

Click to learn more

Click to learn more

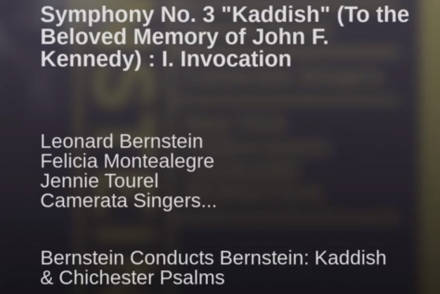

Symphony No. 3 "Kaddish" (To the Beloved Memory of John F. Kennedy) : I. Invocation

℗ Sony BMG Music Entertainment

℗ Sony BMG Music Entertainment

Review Leonard Bernstein's 'Kaddish' Symphony: A Crisis Of Faith From "NPR" 2012