Latest News

Leonard Bernstein's MASS at 50

Posted January 19, 2022

Leonard Bernstein's MASS at 50

By Edward Seckerson

(originally published in the liner notes for the Sony Classical 50th Anniversary MASS remastered edition)

It was back in 1989 during an extensive interview with Leonard Bernstein - one of the last he ever gave - that I experienced what I believe would now be referred to as ‘a moment’. We were discussing the extraordinary work enshrined in this album - MASS - A Theatre Piece for Singers, Players, and Dancers - and had simultaneously happened upon, indeed singled out, a favorite passage - or as Lenny put it ‘a song about the writing of a song’. It’s the sequence that sits at the climax of the ‘Sanctus’ and begins with the Celebrant of this wildly unorthodox Mass idly plucking at his guitar, a solitary note, a ‘Mi’. ‘Mi alone is only me…’ Geddit? But suddenly there is a second note - ‘Mi with sol’ (me with soul) - and with that second note we hear the beginnings of a melody. ‘A song is beginning, is beginning to grow, take wing and rise up singing from me and my soul…’ And as Bernstein spoke the words, he instinctively began to sing them in that ill-tuned unmistakably gravelly voice of his - and in the magic of that moment I could hear, like a startling action replay, the way in which that melody had first evolved…in the singing of it.

So stunned was I by this spontaneous re-enactment of the muse descending that I rather embarrassingly declared (as only a fledgling journalist could) that I believed MASS would come to be regarded as his most important piece. There, just like that, I had said it. And now, 50 years on from the work’s inception, I can say it again and more than ever believe it to be true. Put simply, no other work of Bernstein’s encapsulates exactly who he was as a man or as a musician; no other work displays his genius, his intellect, his musical virtuosity and innate theatricality quite like MASS.

It was written in response to Jackie Kennedy’s suggestion that Bernstein write the inaugural centerpiece for the opening of the John F, Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, DC, in 1971. The work, it was suggested, should take account of the different disciplines that would be showcased in the venue. Ambition and Celebration were the watchwords. And so MASS was born in the larger-than-life image of Bernstein himself. At its core - and this was beyond audacious coming as it did from a Jew - was the sacred text of the Roman Catholic Mass. But it was a text under scrutiny. Under duress. In collaboration with the then only 23-year-old Stephen Schwartz (composer of Broadway shows from Godspell to Wicked) Bernstein’s theatrical objective was to challenge those texts from the perspective of the world as it then was - or rather America as it then was in the age of flower power and peaceniks: a nation caught up in an unpopular war in Vietnam, a nation ravaged by political and racial conflict (the war at home), a nation in protest.

MASS is in so many ways the ultimate protest piece. But equally it’s a piece about Bernstein’s own crisis of faith. It’s about intellectual rigor versus religious dogma. You might even say that Bernstein is himself the Celebrant - the turbulent priest - ultimately rejected by his own kind for peddling platitudes that he no longer believes leave alone questions. His spectacular breakdown at the climax of the piece is his moment of truth. The questions need answering. He smashes the sacraments and discards the vestments. He is, after all, a man (and a musician) before he is a priest. He must reveal himself.

All human kind inhabits MASS - and all manner of music. A bewildering array of styles in dazzling juxtaposition. Music, says MASS, is Bernstein’s one true religion. Its diversity and fervor can move mountains, transcend all social, political, and religious divides. It has the power to unite and to heal. The mad jubilant eclecticism of MASS - where atonal meets folksy meets soul meets gospel meets rock meets Broadway, where a ‘Simple Song’ sits proudly alongside a tone row - is as much a celebration of Bernstein’s craft as his creed. Or to quote the man himself: ‘Music universally shared is the one sure way to the divine’. There you have it. A religious experience - but with a small ‘r’.

And so, as you listen to this stunning inaugural recording - the soundtrack, if you like, to that momentous 1971 world premiere - you are listening to something unique, you are listening to the gospel according to Lenny realised by Lenny. He knows how every bar, every style, every allusion, goes and his worshipful company of singers and players have learned and prepared the piece with him, through him. Lenny calls his hardcore of vocalists ‘street singers’ and at the beating heart of the piece, challenging the Latin Mass at every turn, are their ‘Tropes’ - songful reflections (among his very finest) penned to express what so many of us will be thinking and feeling.

The Celebrant of Alan Titus - who later in life figuratively set aside his guitar to became a pre-eminent Wagnerian bass-baritone - is Lenny’s kind of singing actor and indeed so acutely is the role ‘in his voice’ that it’s hard to believe that this most challenging of roles wasn’t written expressly for him. His climactic ‘mad scene’ always strikes me as Bernstein’s oblique homage to Britten’s Peter Grimes - an opera he revered and indeed premiered in the US. But when you look at the scene objectively it is surely the only possible response to the extended passage where MASS effectively goes nuclear and Bernstein builds a wailing wall of sound (electric guitars et al) around the remorseless repetition of a ten-bar refrain flashing the words ‘Dona nobis pacem’. The plea for peace turns into a demand. This is a climax no other in 20th century musical literature.

But like pretty much everything Bernstein ever gave us MASS does end hopefully. And peacefully. A burgeoning D major canon conveys the words ‘Lauda, Laude’ into the happily thereafter and Bernstein, ever the optimist or hopeful pessimist, casts his healing light over one last statement of his chorale ‘Almighty Father’, a quietly overwhelming nod to Bach, one composer to another.

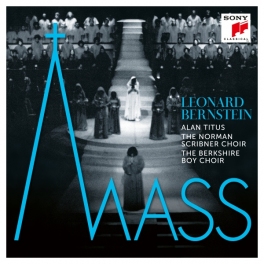

Photo: MASS, 1971. Photo by Fletcher Drake, courtesy of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts Archives.