Works Vocal Psalm 148 (1935)

Overview

While this early Bernstein composition gives no indication of his eventual compositional style, it does reveal the musical environment to which he was exposed as a youngster at his family’s congregation—specifically the music of Solomon Braslavsky. In 1962 Bernstein subsidized the publication of Braslavsky’s setting of one of the central prayers of the High Holy Day liturgy, Un’tane tokef,in appreciation of the man who had meant so much to him in his youth. We hear some of that Braslavsky influence in this Psalm setting, which in turn refers to Weber, Mendelssohn, and other Romantic composers. The work begins with grave chords, à la Handel, but with Wagnerian harmonies. There is even a hint of Mahler in the Allegro agitato section. The manuscript is dated September 5, 1935. Bernstein rediscovered the piece in the mid-1980s, and even though he recognized its Victorian excesses as well as its schoolboyish weaknesses, he expressed an affection for its innocent sweetness.

© 2003 Jack Gottlieb (Written for the Milken Jewish Archive Label, CDs distributed by Naxos International)

Lyrics

Sung in English

Text: adapted by the composer

Praise ye the Lord, Praise Him all the earth,

Praise ye the Lord, monsters of the sea;

Praise Him, ye vagrant flocks of the lea!

Praise the Lord, Praise Him whatever ye may be!

Bless Him all ye stars of light,

Praise Him, mountains, day and night;

Stormy winds rebelling

Seas and oceans swelling

Skies His grandeur telling,

Praise Him!

Beast of the field, rover of the lea!

Fowl of the air, monster of the sea,

Every shrub and tree!

Youth and maiden, sage and child,

Praise with harp and timbrel wild.

Sing His praises near and far,

Sing sun and moon, Sing oh morning star,

Princes and judges, assemble, assemble,

And praise ye the Lord.

Praise! For His is the glory, Halleluya!

A Brief Examination of Leonard Bernstein’s Psalm 148

By: Dr. Ann Glazer Niren

People the world over know the music of Leonard Bernstein. His works have been featured widely on Broadway and the concert stage, providing ample fodder for scholarly review. However, a little-known Bernstein piece, Psalm 148, for voice and piano, provides clues to his later style. Bernstein composed Psalm 148, his earliest published work, in 1935 when he was seventeen.

Bernstein does not specify a voice type, writing only “voice.” He composed in a range that would suit a mezzo-soprano or a tenor. The psalm, a song of praise to God, is a genre with which Bernstein was familiar, having been a regular worshipper at his Boston synagogue, Mishkan Tefila. However, the fact that he chose to set this work in English rather than Hebrew perhaps indicates that he wanted the work to be accessible to a larger population. Although the piece is clearly spiritual, it is not necessarily liturgical, and therefore, could be performed in the concert hall as well as a synagogue or even a church.

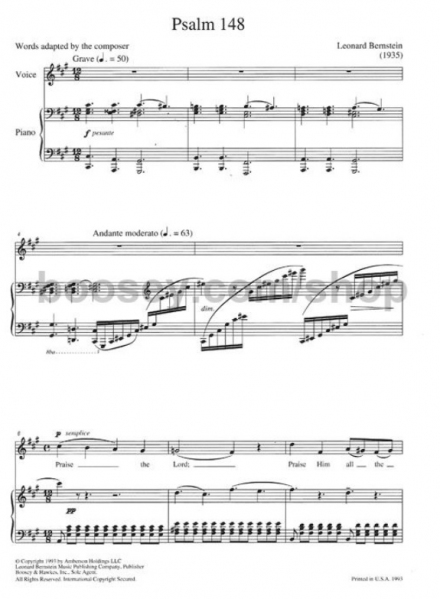

This work exhibits more influence from nineteenth-century composers than most of Bernstein’s works. The opening introduction bears a resemblance to Chopin’s Prelude in C Minor, op. 28, no. 2. Additionally, this introduction serves to unify the sections of the piece, and in this way, is reminiscent of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 13 in C Minor (“Pathétique), a work that Bernstein possibly knew at this point in his life.

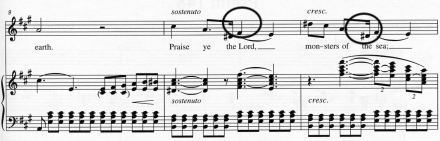

After the short introduction, the voice enters along with a change in the accompaniment. The melodic line remains fairly conservative, lacking Bernstein’s characteristic rhythmic vitality, melodic inventiveness, and large leaps. However, these elements occur in the next section, allowing the listener a glimpse of his future style. For example, although the melodic line in the vocal part appears to be mostly diatonic, D-sharp occurs consistently. It seems initially that this pitch acts as a lower neighbor to E. However, the D-sharp also outlines a tritone with the appearance of A (Example 1). Bernstein’s later style, particularly in West Side Story (1957), shows a predilection for this interval. There are some larger leaps and more jagged rhythms, characteristics often favored by Bernstein.

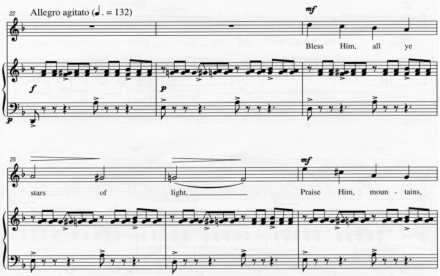

The next section features a fast accompaniment in D minor. Although the time signature remains the same, the triplet groupings give this section a dance-like feel. The melody seems new, in part because of tempo and key changes, but it derives from the vocal line in the previous section (Example 2). The vocal line utilizes more chromaticism, but the tritone motive returns, providing unity. Bernstein presents a series of modulations, each occurring more emphatically, accompanied by a long-term crescendo, climaxing in a fortississimo. The piece concludes in A Major with a return to the original introductory idea. In many ways, the harmonic ambiguity serves to underscore the text.

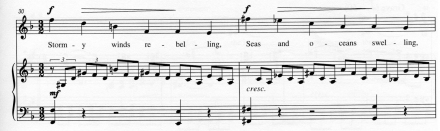

Bernstein’s text is longer than the Biblical one, and while it maintains some of the imagery and wording of the original, it adds some of its own lyrics which elaborate on the verses. His interpretation vividly captures the meaning of the psalm while adding his own touch. He includes examples of text painting, such as arpeggiated diminished triads, a descending melodic line, and a louder dynamic to accompany the text “stormy winds rebelling” in measure 30 (Example 3). Similarly, in measures 48-50, in which the text states, “princes and judges, assemble,” there is an allargando accompanied by thick, dense chords, as if to summon a procession. Sometimes, though, Bernstein works against conventional expectations. For example, we would expect “earthly” beings, such as “princes and judges assemble,” to be set in a lower register. However, Bernstein continues an overall melodic ascent throughout the piece, so that when he reaches the latter text beginning in measure 49, he sets it in a higher register than we would expect. Immediately thereafter, the melodic line reaches its apex at F-sharp on the word “Praise.” Therefore, sometimes Bernstein consciously uses text painting and other times, he works against our expectations.

Although this composition sounds harmonically quite different than the Bernstein music with which we are familiar, it does offer some hints of the future Bernstein style. Psalm 148 illustrates a penchant for the dramatic, through key and tempo change and text painting, for rhythmic intensity, tritone intervals, and lyrical vocal lines. While this work does not offer the mature style of West Side Story or Mass, its interest for us is the promise of great things to come.

Related Works

Symphony No. 1: Jeremiah

Chichester Psalms

Halil: Nocturne

Simchu Na

Hashkiveinu

Hashkiveinu

Silhouette (Galilee)

Shivaree

Four Sabras

Yigdal

Vayomer Elohim

Reenah

Bridal Suite

Details

To perform Psalm 148, please contact Boosey & Hawkes. For general licensing inquiries, click here.

Media

Recording cover

Milken Archive of Jewish Music

Milken Archive of Jewish Music

Sample Page

Boosey & Hawkes

Boosey & Hawkes

Example 1 Psalm 148, measures 9-11

A Brief Examination of Leonard Bernstein’s Psalm 148

A Brief Examination of Leonard Bernstein’s Psalm 148

Example 2 Psalm 148, measures 22-27

A Brief Examination of Leonard Bernstein’s Psalm 148

A Brief Examination of Leonard Bernstein’s Psalm 148

Example 3 Psalm 148, measures 30-31

A Brief Examination of Leonard Bernstein’s Psalm 148

A Brief Examination of Leonard Bernstein’s Psalm 148

Saul and David (between 1650-1670)

Rembrandt van Rijn

Rembrandt van Rijn

Psalm 148

℗ 2003 Milken Family Foundation

℗ 2003 Milken Family Foundation